“I have a dream” – Mural by Fabian Bane Florin and Pest in Chur, Switzerland

Muralist Fabian Bane Florin

“I have a dream” from 2015 by Fabian Bane Florin and Pest in Chur, Switzerland.

About the mural: This project was developed in cooperation with the City of Chur and the Cultural Office of Chur. The Lachen school is located in the neighborhood where Bane grew up. This was an important project for him and an opportunity to give something back to his beautiful hometown.

More by Fabian Bane Florin: “The Plessurfischer” – Mural by Fabian Bane Florin in Chur, Switzerland

Comments:

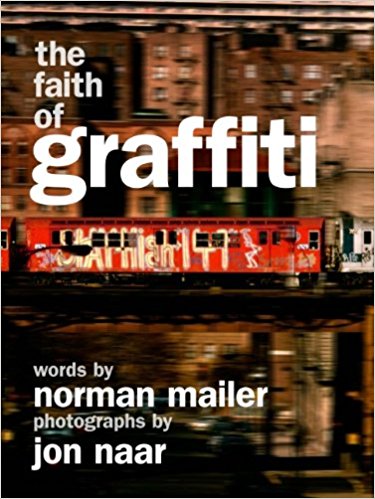

Jon Naar – Photographer, Faith of Graffiti

It is with great sadness that we just learned of Jon Naar’s passing. Jon took the photographs for Faith Of Graffiti, the seminal book on subway art in 1972. His eye for design brought a new perspecitve to “vandalism” and facilitated Norman Mailer’s essay where he calls graffiti, art. We became friends with Jon just over the past decade. We were happy to collaborate with him to create a limited edition book + print package when the soft cover of Faith Of Graffiti was released and adding a limited edition print of “Red Bird” to accompany the book.

We were entertained by his stories of his time in British Intelligence and of the day he stepped out of the subway station at 125th street and met his young “writers”. Jon was always active and up for a new project. His passion never waned and his energy contagious.

One of our favorite moments was when we collaborated with Jon at Knoll for a panel discussion including Massimo Vignelli (creator of the subway graphic design) and Mike 171 and Butler, graffiti artists from Faith of Graffiti. Massimo had never met a graffiti writer and of course, the writers had not met the designer. When Massimo learned why Mike 171 and Butler were writing on the walls, signage and trains, he had a new perspective and new respect for what he had previously considered vandalism. We are thankful to Jon for being the catalyst of this converstaion.

Our thougths are with Jon’s family.

Sara + Marc

‘Annihilation,’ ‘Support the Girls’ and More Streaming Gems

‘Annihilation’ (2018)

You’d think that a science-fiction adventure featuring the “Star Wars” alums Natalie Portman and Oscar Isaac, as well as Portman’s “Thor” co-star Tessa Thompson, would have been a giant hit. But Paramount Pictures seemed baffled by how to market a sci-fi picture about ideas and creeping dread (rather then lasers and intergalactic dogfights), dumping it onto Netflix overseas and into theaters with a shrug in the United States. They fear what they don’t understand; the writer and director Alex Garland, adapting the novel by Jeff VanderMeer, crafts a thrilling yet thoughtful combination of head trip and hero’s journey that owes more to Tarkovsky than Lucas.

‘On the Count of Three’ (2022)

The feature directorial debut of the stand-up comic and sitcom star Jerrod Carmichael was one of many films all but disappeared by the pandemic; it premiered at the 2021, online-only edition of the Sundance Film Festival before quietly landing on Hulu more than a year later. But there’s much to recommend in “On the Count of Three,” the story of two longtime friends (played by Carmichael and Christopher Abbott) who vow to aid each other in ending their lives after a long day of cleaning up unfinished business. Its chief virtue is its leading actors — Abbott has been doing modest but devastating work on the indie scene for years, and Carmichael matches his co-star’s intensity and anguish — while Carmichael shows a sure hand for navigating the tonal shifts of Ari Katcher and Ryan Welch’s tricky screenplay.

The films of the director Gregg Araki have been so (rightly) celebrated in recent years for their wild stylistic choices and unapologetic queer themes that it’s tempting to overlook his more tempered, mainstream affairs. But this combination of sun-baked noir, coming-of-age drama and Sirkian melodrama remains one of his most fascinating concoctions. Shailene Woodley turns in one of her finest performances to date as young Kat, whose mother, Eve (Eva Green, vamping marvelously), disappears under mysterious circumstances. Kat tries to figure out what happened, but “White Bird” is less a detective story than an exploration of the tricky landscape of young adulthood, dramatized with a weary verisimilitude.

‘Violet & Daisy’ (2013)

This tale of two teenage girl assassins (Alexis Bledel and Saoirse Ronan) from the writer and director Geoffrey Fletcher (the Oscar-winning screenwriter of “Precious”) suffers a bit from post-Tarantino preciousness. The M.V.P. here is James Gandolfini, who co-stars as their would-be target, and plays the character with the weary melancholy of a man who knows his days are numbered, and has accepted it. He plays it as dry comedy, with just a touch of doomed inevitability, and that’s the right choice; the genuine tenderness and trust in his scenes with Ronan are a nice plus. “Violet & Daisy” hit theaters just 12 days before Gandolfini’s untimely death, and it serves as a poignant reminder of the wide range of roles he had yet to play.

Kodi Smit-McPhee’s Oscar-nominated turn in “The Power of the Dog” was not the actor’s first go-round in the Wild West; six years earlier, he co-starred with Michael Fassbender in this eccentric and affecting oater from the writer and director John Maclean. Smit-McPhee plays Jay, a teenage Scottish immigrant traveling the West in search of his sweetheart from back home, with Fassbender as Silas, a frontiersman who takes the innocent and clueless Jay under his wing. MacLean creates a credibly dangerous world of threats both natural and seemingly supernatural (Ben Mendelsohn, stealing the show as a menacing bounty hunter).

‘Support the Girls’ (2018)

The writer and director Andrew Bujalski (“Funny Ha Ha,” “Computer Chess”) creates what looks, on its shiny surface, like a sunny workplace comedy along the lines of “Working …” or the Chotchkie’s scenes in “Office Space.” But he’s up to something much slyer, a smart examination of class and gender politics in one of their most pointed playgrounds: a Hooters-style sports bar and grill, where customers leer at scantily clad waitresses while the manager, Lisa (Regina Hall), tries to keep temperatures cool (and maintain her own sanity). It’s a wise, winning comedy, with a particularly sparkling supporting turn by Haley Lu Richardson, a “White Lotus” favorite.

‘Voyeur’ (2017)

The strange, twisted tale of the motel owner Gerald Foos (who claimed to have spied on his customers for decades) and the superstar journalist Gay Talese (who wrote about Foos in a controversial “New Yorker” article and book) is detailed by the directors Myles Kane and Josh Koury in this riveting documentary. Voyeurism aside, the most compelling passages are less about what Foos did than how Talese’s seemingly sturdy news judgment failed him so spectacularly. Ultimately, “Voyeur” is less a character study than a prescient examination of a faltering media landscape, where a story that’s too good to be true is too often told anyway.

‘VHS Massacre’ (2016) / ‘VHS Massacre Too’ (2020)

Kenneth Powell and Thomas Edward Seymour’s first documentary on, per the secondary title, “Cult Films and the Decline of Physical Media” is a bit too ambitious for its slender 72-minute running time, attempting to follow too many strands and chase too many gimmicks. But the most direct material, on the logistics of the video business — from its golden age to this waning period — is invaluable, as Seymour seemed to realize when solo-directing the more successful follow-up, a straight-ahead history of exploitation films, their exhibition and the kind of oddities we’ve lost in this all-streaming, all-the-time era. The sequel is the better film, but both are informative and enlightening, with copious commentary from the people who make these movies, and those who love them.

Art, entertainment, and the hard-boiled mystique

The Maltese Falcon (1941).

DB here:

The traditional opposition between Art and Entertainment still holds some sway. Art, some believe, is the realm of higher significance and profound emotion, while entertainment yields mere diversion and superficial engagement. Art embodies wisdom and technical breakthroughs, while at best entertainment is home to talent and cleverness. Art harbors genius, entertainment offers ingenuity. Art expresses the creator’s personal vision, entertainment recycles collective fantasy (or the Zeitgeist). There’s usually an implied hierarchy of quality and of appeal: art is for a sensitive elite, entertainment is popular (read vulgar).

One problem, though, is that for long stretches of history much art has been thoroughly entertaining. Mozart, Shakespeare, Dickens, Hiroshige, Austen, and many other major artists have found wide popularity. They provide pleasure aplenty. But with urbanization and the rise of capitalism, mass production created a huge public, and tastemakers have tended to treat art as a realm apart. For a hundred years or more, entertainment has been equated with mass culture, and art with high culture, most notably with modernism and its successors.

Another problem is cultural endurance. In a recent column, Michael Dirda points out that genre fiction often outlasts prestigious literary fiction of its era.

Take fantasy and science fiction: In 1997, I praised William Gibson’s “Neuromancer,” John Crowley’s “Little, Big,” Gene Wolfe’s “Book of the New Sun” and the works of Ursula K. Le Guin — all remain vital to contemporary writers and readers.

Similarly, classics of mystery fiction by Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Patricia Highsmith still attract readers, while “mainstream” novels of their eras are forgotten. Dirda’s second point is no less valid.

More generally, American novelists have wholly embraced the energy and potential of fantasy in its various forms. We are all fabulists now. This century revels in comics, graphic novels, manga and superhero movies. Authors as varied as Colson Whitehead, Walter Mosley, Kelly Link, Jonathan Lethem, Elizabeth Hand and Michael Chabon, to name a few prominent figures, all grew up loving fantasy and science fiction.

Genre appeals have infiltrated prestige literature, as in the crime plots of Graham Greene, Joyce Carol Oates, and Richard Price. (I consider Colson Whitehead’s and Richard Wright’s contributions here.) Likewise, we have horror-infused tales like George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo and Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home .

Creators of entertainment have felt the distinction keenly. “A wedge has been driven into the industry,” says Christopher MacQuarrie, director of the latest Mission: Impossible installment. “Are you an artist or an entertainer? Tom doesn’t see them as mutually exclusive.” But some creators have seen a forking path. Rex Stout, after several “serious” novels failed, came to two conclusions:

First—that I was a good storyteller, and second—that I would never be a great novelist. I’d never be a Tolstoy, or a Dickens, or a Balzac…. So since that wasn’t going to happen, to hell with sweating out another twenty novels when I’d have a lot of fun telling stories which I could do well and make some money on it.

The Art/ Entertainment distinction runs through my recent book, Perplexing Plots, because many mystery writers have aimed at “elevating” their work to the level of prestige literature. This urge drives them to experiment with the norms of plotting and writing. Even when the genre limits remain in force, there’s a chance that skillful exponents can accept them and still yield “literary” pleasures. A good example is what happened to hard-boiled detective fiction in the hands of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

The Op

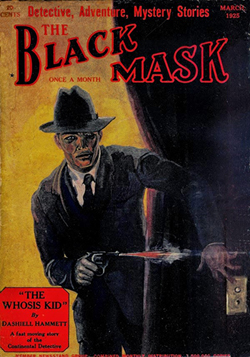

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Black Mask stories put a premium on action, so the Op was often at the center of violence perpetrated by crooks, sociopaths, and corrupt cops. Unlike other hard-boiled detectives, the Op isn’t a swaggering sadist. Violence is his last resort; he favors obstinate everyday professionalism. Sometimes he’s fooled by the grifters and has to wriggle his way out. At other times, he can set crooks against one another and watch the mutual destruction.

Hammett wrote the stories in the first person, giving the Op a telegraphic, visceral style laced with sour humor. A 1923 story shows his American vernacular already in place.

Just at the wrong minute Henderson decided to look over his shoulder at us–an unevenness in the road twisted his wheels–his machine swayed–skidded–went over on its side. Almost immediately, from the heart of the tangle, came a flash and a bullet moaned past my ear. Another. And then, while I was still hunting for something to shoot at in the pile of junk we were drawing down upon, McClump’s ancient and battered revolver roared in my other ear.

Henderson was dead when we got to him–McClump’s bullet had taken him over one eye.

McClump spoke to me over the body.

“I ain’t an inquisitive sort of fellow, but I hope you don’t mind telling me why I shot this lad.” (“Arson Plus”)

In 1929, the publisher Knopf issued two Hammett novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, based on Black Mask serials. The Op had not lost his wit or his gift for staccato narration. Here are three excerpts.

I didn’t think he was funny, though he may have been.

He stood at the foot of the bed and looked at me with solemn eyes. I sat on the bed and looked at him with whatever kind of eyes I had at the time. We did this for nearly three minutes.

The latch clicked. I plunged in with the door.

Across the street a dozen guns emptied themselves. Glass shot from door and windows tinkled around us.

Somebody tripped me. Fear gave me three brains and half a dozen eyes. I was in a tough spot. Noonan had slipped me a pretty dose. These birds couldn’t help thinking I was playing his game.

I tumbled down, twisting around to face the door. My gun was in my hand by the time I hit the floor.

Across the street, burly Nick had stepped out of a doorway to pump slugs at us with both hands. I steadied my gun-arm on the floor. Nick’s body showed over the front sight. I squeezed the gun. Nick stopped shooting. He crossed his guns on his chest and went down in a pile on the sidewalk.

Hands on my ankles dragged me back. The floor scraped pieces off my chin. The door slammed shut. Some comedian said:

“Uh-huh, people don’t like you.”

As he was finishing The Dain Curse, Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf confessing that in future work he wanted to go beyond Entertainment to Art.

I’m one of the few—if there are any more—people moderately literate who take the detective story seriously. I don’t mean that I necessarily take my own or anybody else’s seriously—but the detective story as a form. Some day somebody’s going to make “literature” of it (Ford’s Good Soldier wouldn’t have needed much altering to have been a detective story), and I’m selfish enough to have my hopes, however slight the evident justification may be.

The question is: How to do this?

Inside and outside

Hammett proposed an answer in his letter to Blanche Knopf. He wanted to try that he wanted to try out modernist technique in a third novel.

I want to try adapting the stream-of-consciousness method, conveniently modified, to the detective story, carrying the reader along with the detective, showing him everything as it is found, giving him the detective’s conclusions as they are reached, letting the solution break on both of them together. I don’t know whether I’ve made that very clear, but it’s something altogether different from the method employed in “Poisonville [Red Harvest],” for instance, where, though the reader goes along with the detective, he seldom sees deeper into the detective’s mind than dialogue and action let him.

His mention of stream of consciousness may mislead us about his intentions. In that technique the verbal narration seeks to mimic the flow of the mind as it flits across sensory impressions, memories, and fantasies. The process is often rendered as sentence fragments, often introduced by a sentence indicating the behavior of the character.

Here’s an example from Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), the most famous showcase of stream of consciousness. Mr. Bloom is in a Catholic church.

He saw the priest stow the communion cup away, well in, and kneel an instant before it, showing a large grey bootsole from under the lace affair he had on. Suppose he lost the pin of his. He wouldn’t know what to do to. Bald spot behind. Letters on his back I.N.R.I? No: I.H.S. Molly told me one time I asked her. I have sinned: or no: I have suffered, it is. And the other one? Iron nails ran in.

Sometimes the images and phrases are separated by commas and periods, but sometimes they simply pile up. In the book’s last chapter, Molly Bloom’s drowsy imaginings are given in an unpunctuated, sparsely paragraphed flow.

It’s likely that Hammett didn’t want his usage to be as fragmentary as what we encounter in Joyce and others. His invocation of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915) suggests something closer to what many now call inner monologue. (Ford called it “impressionism.”) Here the flow of thought is given as a sort of soliloquy, a flow of more or less cogent and coherent ideas and impressions. What makes it a modernist technique is that inner monologue may not respect story chronology and it’s likely to be biased, uncertain, equivocal, and subject to revision. Ford’s narrator, John Dowell, tells a rambling, out-of-order tale of marital infidelity and suicide, in which flashbacks are analyzed and re-analyzed.

Looking over what I have written, I see that I have unintentionally misled you when I said that Florence was never out of my sight. Yet that was the impression that I really had until just now. When I come to think of it she was out of my sight most of the time.

At the climax, Dowell makes a provisional sense of what the characters knew and why they acted as they did.

The problem in importing this to the detective story is evident. How can the detective’s ongoing reasoning, bristling with mistaken inferences and reconstructed impressions, be passed along to the reader without causing confusion? For this reason, detective story narration, whether first-person or third-person, suppresses most of the protagonist’s reasoning. The Watson figure and the dumb authorities exist to be baffled and play with misleading possibilities while the detective holds back even a partial solution.

By convention, the climax of the tale is the revelation of the truth–not when the detective discerns it, but at the moment when it can be announced with decisive impact (often in a gathering of suspects with the police present). Raymond Chandler noted that the delayed revelation was a serious constraint of the genre, even when the detective, like the Op, is telling the story. “The first person story is assumed to tell all but it doesn’t. There is always a point at which the hero stops taking the reader into his confidence.” The detective “stops thinking out loud and ever so gently closes the door of his mind in the reader’s face.” This prevents the public announcement of the solution from being anticlimactic.

Worse, Ford’s protagonist Dowell is an unreliable narrator, as the above passage suggests. To make the detective’s first-person account unreliable would be more than a “convenient modification” of the standard plot schema. It would push toward the experiments seen in Cameron McCabe’s The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937) and later “anti-mysteries.”

Hammett admitted in a later letter that he would put the “stream-of-consciousness” experiment on hold while he wrote material for Hollywood in “more objective and filmable forms.” (That would include his script for City Streets of 1931, which does include a subjective auditory flashback rare in films of the time.) But in his next novels Hammett turned sharply away from the interiority he had considered. Instead, he went toward extreme objectivity, almost completely shutting us out from his protagonists’ inner lives.

The action of The Maltese Falcon (1930) and The Glass Key (1930) attach us closely to his protagonist, scene by scene. We’re confined to his activity and his range of knowledge. But this doesn’t get us into his mind. For these books Hammett switched to third-person narration and made it radically objective, sticking almost completely to reporting dialogue and character interaction.

In Perplexing Plots, I explore how this strategy works, but here’s an example from The Glass Key.

At Madison Avenue a green taxicab, turning against the light, ran full tilt into Ned Beaumont’s maroon one, driving it over against a car that was parked by the curb, hurling him into a corner in a shower of broken glass.

He pulled himself upright and climbed out into the gathering crowd. He was not hurt, he said. He answered a policeman’s question. He found the hat that did not quite fit him and put it on his head. He had his bags transferred to another taxicab, gave the hotel’s name to the second driver, and huddled back in a corner, white-faced and shivering, while the ride lasted.

The narration presents what a third-person observer would have seen and heard, and it won’t venture into Beaumont’s thinking. The cues are behavioral: he seems cool enough in slipping out of the crash, but his true reaction is given through his nervous reaction while riding back to the hotel.

As Hammett’s second letter to Blanche Knopf suggests, this flat objectivity would seem an ideal novelistic basis for a “filmable” treatment. John Huston’s screen adaptation of The Maltese Falcon confines us almost completely to Spade’s range of knowledge. (The big exception is that we see his partner Miles Archer shot by an unknown killer.) The film’s visual narration mostly follows Hammett’s impassive neutrality. But when Casper Gutman drugs Spade, we get Spade’s clouded optical viewpoint.

In the novel the narration reports that Spade’s eyes seemed to muddy over. When he says, “And the maximum?” we’re told that “An unmistakable sh followed the x in maximum as he said it.” This isn’t Spade’s experience but rather what an observer would register, an “unmistakable” impression confirmed when we’re told that “a sharp frightened gleam awoke in his eyes.” As Spade tries to walk, he’s tripped by Wilmer. He falls and Wilmer kicks him. “Once more he tried to get up, could not, and went to sleep.” The whole scene is rendered externally.

So instead of giving the detective story a modernist subjectivity, Hammett went to the other extreme. Did he intuitively recognize the problem of revealing the detective’s inferences too soon? Maybe, although his increasing involvement with Hollywood may have kept him on the objective, “filmable” path. The Thin Man (1934), his last novel, is a fascinating effort to return to first-person narration while incorporating the dry objectivity of the two previous books.

Perhaps inadvertently, Hammett’s radicalization of the objective method yielded what he had hoped for. The Maltese Falcon was greeted as a serious work of literature and was soon incorporated into the prestigious Modern Library series. His works have become part of the canon of American letters enshrined in the Library of America collection. The convention of delaying the detective’s solution didn’t prevent the genre from becoming accepted as a legitimate literary form–at least as practiced by Hammett, and his most prominent successor.

Overtones, echoes, images

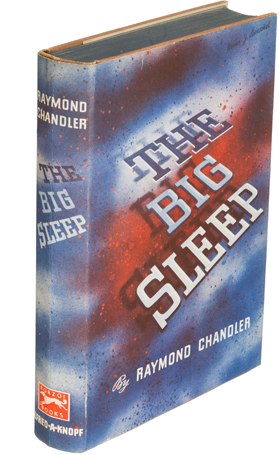

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

But what Chandler means by “understanding” doesn’t include full-blown reasoning. First-person narration, he explains in a 1949 note, must “suppress the detective’s ratiocination while giving a clear account of his words and acts and many of his emotional reactions.” This seems a response to the detached reportage of late Hammett prose. Chandler also rejects the Op’s streetwise patter by explaining to Knopf that his method will use “a very vivid and pungent style, but not slangy or overtly vernacular.” He wants “to acquire delicacy without losing power.”

Hammett, while a voracious reader, learned a good deal of his craft from actually investigating crimes. Chandler, who began writing mysteries as Hammett’s productivity tailed off, owed his knowledge of the mystery genre to reading. He studied crime fiction of all sorts with almost academic passion and became one of the most nuanced commentators on the tradition. He claimed to have learned plotting from outlining pulp stories by Erle Stanley Gardner. His literary tastes didn’t run to modernism. He admired the Greek and Roman classics, Flaubert, James, and Conrad and thought highly of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Hammett imagined elevating the genre by “conveniently modifying” modernist technique, but Chandler sought to make the hard-boiled detective story more like the ambitious mainstream novel.

He believed he could do that through style. In his crucial essay, “The Simple Art of Murder (1944/1946),” he praises Hammett’s prose but objects that “it had no overtones, left no echo, evoked no image beyond a distant hill.” Chandler sought to give style a greater novelistic richness not only through probing his protagonist’s mind but also through fairly dense descriptions colored by the protagonist’s emotions and judgments.

Hammett sketches characters in quick strokes and he merely indicates settings. But Chandler dwells on his characters and their surroundings. The opening of The Big Sleep devotes a page and a half to Philip Marlowe’s impressions of the Sternwood mansion (stained-glass window of a knight rescuing a lady, plush chairs, a mysterious portrait) and another page and a half to his meeting with the coy Carmen. These are filtered through Marlowe’s running commentary. The knight doesn’t really seem to be trying. The chairs appear to never have been sat in. The portrait looks threatening. Carmen’s infantile flirtation reveals that “thinking was always going to be a bother to her.” Here are the overtones and echoes that Chandler finds lacking in Hammett. This is an ominous household–as Marlowe will later say, this will be “no game for knights.”

Chandler would pursue this method in the following novels. Yet at times the narration plunged deeper into subjectivity. In Farewell, My Lovely (1940) Marlowe is repeatedly knocked out in tussles, and in the second passage Chandler writes:

The man in the back seat made a sudden flashing movement that I sensed rather than saw. A pool of darkness opened at my feet and was far, far deeper than the blackest night.

I dived into it. It had no bottom.

The film adaptation, titled Murder, My Sweet (1944), uses this subjective device in every knockdown. Marlowe’s voice-over narration runs through the film, and after the first assault we hear:

I caught the blackjack right behind my ear. A black pool opened up at my feet. I dived in. It had no bottom.

Onscreen we see Marlowe’s crumpled body blotted out by a miasma that leads to a black frame.

In a later sequence, a knockout of Marlowe is rendered as wild optical exaggerations before following the novel’s report of Marlowe seeing a room full of smoke. That’s translated as wispy superimpositions over the shots, with explanatory voice-over.

The film tries a bit too hard, but its use of voice-over and delirious visual subjectivity would become common in film noirs of the period.

In Farewell, My Lovely, Marlowe’s recovery from his first knockout is rendered with vigorous subjectivity across two pages, as Marlowe realizes that the voice he hears reviewing what happened is his own. “I was talking to myself, coming out of it. I was trying to figure the thing out subconsciously.”

Marlowe is able to reconstruct bits of the crime through this process, but it’s a provisional solution, not the decisive one. That one he keeps from the reader until the climax. By then, as per convention, the door to his mind has shut in the reader’s face.

Hammett’s novels were published when most crime fiction consisted of genteel whodunits and gangster sagas, so he had the advantage of novelty. By the time Chandler published The Big Sleep, he was competing with many book-length stories of hard-boiled investigators. Aware of the need to establish a distinctive presence, he presented work that stood apart by its social criticism and the romanticized realism of a righteous avenger alone on the mean streets of a corrupt city–sure-fire attractions to intellectuals then and since. Just as important was his self-consciously literary style. “In the long run, however little you talk or even think about it, the most durable thing in writing is style, and style is the most valuable investment a writer can make with his time.”

Through concern with language’s echoes and overtones, he established himself as Hammett’s successor. The literati followed his lead and declared him a significant novelist. His books, along with “The Simple Art of Murder,” provided an enduring rationale for the tough detective story. While adhering to the conventions of the classic puzzle (clues, faked deaths, false identities, least-likely culprit), he acquired lasting prominence. Like Hammett he has found a home in the Library of America.

Arguably Hammett and Chandler also elevated their genre. Their achievements encouraged other ambitious writers and stimulated critics and readers to look more closely at the possibilities of the murder novel. No wonder that prestigious writers have turned to mystery plots. Fans still labor to make a case for Golden Age puzzles as art rather than entertainment, but most critics and readers assume the hard-boiled mystery to be at least potentially serious literature–especially when it goes under the alias “noir.”

Nowadays the Art/ Entertainment duality has weakened its hold. If, as Dirda suggests, we are all fabulists now, we’re also probably mystery fans to some degree. It’s likely that film played a role here, in showing intellectuals that films by Hitchcock, Ozu, and other popular directors were of high quality. More and more, I think, people aren’t as eager to see the split as absolute. Instead of a hierarchy, we have more of a spectrum.

In harmony with this, Perplexing Plots argues that culture offers us a plenitude of individual works with varied appeals, all of which can be realized with, to use Chandler’s terms, delicacy and power. Some works rely on subtlety, others on immediate impact. We have the refinements of Baroque music and the direct force of The Rite of Spring. If Treasure Island is a masterpiece a well as a rousing yarn, so is Die Hard. There is heavy art and light art, brooding art and and diverting art, intellectual density and emotional charm. None of these qualities is simple or easy to achieve; all can repay analysis. The slogan might be: “There’s valuable work at all levels. And there are no levels.”

One source of value, not always acknowledged, is the role of entertainment in revealing fresh expressive possibilities in the medium. For example, the martial arts cinemas of Japan and Hong Kong opened up new vistas of cinema. And yes, as Hammett and Chandler indicated, a lot of the freshness lies in style. This is why Perplexing Plots spends time looking closely at how mystery fiction and film work, word by word or shot by shot. Even Agatha Christie’s supposedly bland verbal texture points up ways in which language can mislead us.

So Hammett and Chandler didn’t “elevate” the hard-boiled story so much as blur the line between genre fiction and the “legitimate” novel. Ambler and Le Carré did the same for the spy story, as did Highsmith for the psychological thriller. For such reasons, Perplexing Plots discusses hard-boiled detection extensively. I explore the Art/ Entertainment distinction because it has obsessed critics and creators. But I try not to buy into the split, opting instead for the looser idea of “crossover.” It’s a swap meet, with storytellers ransacking works “high” and “low” for subjects, forms, techniques, whatever.

I wanted to put up this entry on 23 July, Raymond Chandler’s birthday. It happens to be mine too. No cheerleading here, though. I prefer Hammett, as maybe you can tell.

My quotations from Hammett’s letters come from Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett, 1921-1960, ed. Richard Layman and Julie Rivett (2002). I take Chandler’s remarks on mystery fiction from Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, ed. Frank MacShane (1981) and Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardiner and Katherine Sorley Walker (1962).

Michael Dirda, as my mentions of him should lead you to expect, has written an admirable example of taking popular storytelling seriously but not solemnly: On Conan Doyle, or the Whole Art of Storytelling (2014). Kristin does something similar in her Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes, or Le Mot Juste (1992), available here and here. Her immensely popular subject, P. G. Wodehouse, was regarded as a master of English prose by Martin Amis, Evelyn Waugh, and many other literary celebrities.

What about the third celebrated hard-boiled pioneer, Ross Macdonald? Read Perplexing Plots to find out!

Murder My Sweet (1944).

This entry was posted

on Sunday | July 23, 2023 at 9:07 am and is filed under 1940s Hollywood, Film and other media, Narrative strategies, PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book).

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

Mum, dad, other: intimate photographs of parents – in pictures | Art and design

Marilyn Minter: Coral Ridge Towers (Mom Dyeing Eyebrows), 1969

Marilyn Minter’s rarely seen black and white photographs of her mother were made in 1969 while she was a student in art school. When classmates first viewed the images, they reacted in shock, exclaiming: ‘Oh my god. That’s your mother?” She had not realised how intensely the images would resonate as her mother, a drug addict suffering from an anxiety disorder, lived in a nightgown, and rarely left the house. Minter did not show the work again until 1994

1000 Words Photography Magazine #18

‘Photography Magazine of the Year’ category at the Lucie Awards 2014, we are delighted

to announce the launch of 1000 Words issue 18. This is

the last release delivered in the current format before we launch our brand new,

fully responsive website in early 2015 so stay tuned for more details!

interesting new talents to emerge from the UK photography scene in recent years,

Peter Watkins. The Unforgetting is a powerful and moving

examination of the artist’s German family history; the trauma surrounding the

loss of his mother to suicide as a child, as well as the associated notions of

time, memory and history, all bound up in the objects, places, photographs, and

narrative fictions that form its structure. The work is accompanied by a text from Edwin Coomasaru, one of the curators of Watkins’ highly-acclaimed

exhibition at the Regency Town House as part of the Brighton Photo Fringe 2014.

rising star, the American photographer Daniel

Shea. Renowned writer and founder of Errata Editions Jeffrey Ladd sits down with Shea’s recently released photobook,

Blisner IL and finds much to celebrate in its pages. This new edition explores the post-industrial fallout of a once prosperous albeit

imaginary Southern Illinois town. It offers a reality woven from an assembly of

disconnected locations – all with their own lineage and history – then it lends

itself as a surrogate to comment on that larger state of a country where

globalisation and demands of economy have long shifted from production.

images from Cameroon’s earliest colour photo studio Photo Jeunesse, now part of

the endlessly fascinating collection of The

Archive of Modern Conflict. As independent curator and academic Duncan Wooldridge notes, the material

represents a record not only of Cameroonian society, tracing tradition and

globalisation but in its loose ends – the details of its painted sets, and the

playful activities of its sometimes quirky sitters – it tells an alternative

story of the photo studio, and its ability to represent not only the formal and

dignified version of the sitter, but the very excess that surrounds them. The

photographs were premiered back in November during Lagos Photo Festival,

Nigeria.

photographers Bill Henson gets his

dues in our review of 1985, his latest book designed by The Entente and

published by Stanley/Barker. “Henson’s camera has the ability, through movement

and then poise, to render the best kind of sombre confusion,” writes Daniel C Blight in his paper. “Henson’s

images are subdued not in time, but over

skies and through buildings,

clouds, naked people, telephone pylons, pyramids and other familiar or

extraneous abstractions. They are seemingly underexposed, but we can’t call

them badly lit. Somewhere between the ambiguity of eventide and its gloaming

opposite, Henson is a wonderer; one whose images intentionally do whatever they

can to avoid stasis and perhaps clarity, within the confines of their static

medium.”

brought to you by the The Photocaptionist Federica Chiocchetti, we take

a look at The Spaghetti Tree by Lucy

Levene, a documentary study of Bedford’s Italian community, the largest

concentration in the UK at more than 14,000 people. Attending events and

accepting invitations to people’s homes, she developed attachments and became

involved in the families’ intimate narratives. Her often witty photographs call into question mythologies of what

it means to be ‘Italian’ and the nostalgic ideal of ‘La Bella Figura’ felt by many as they try to forge an

independent identity in their new home, simultaneously revealing the tensions

in conventional modes of portraiture; the perfect and imperfect image.

Finally,

we send a dispatch from The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, United States on the

occasion of

retrospective exhibition, Storyteller:

The Photographs of Duane Michals. Aaron

Schuman provides a stirring essay, questioning how the artist has

influenced contemporary practice in reference to the current fashion for art-and

photo-historical referencing, appropriation, and photomontage, as represented

by emerging photographers such as Matt Lipps, Brendan Fowler, and Anna Ostoya.

His analysis also takes in the lessons to be found in Michals’ work, from the distinct

power of photographic sequencing, soul-searching, sincerity, and storytelling

as evinced by leading practitioners such as Alec Soth, Paul Graham and others.

by Dutch artist Anouk Kruithof,

which offers

an engaging and individual look at the evolving nature of photography via images from Brad

Feurhelm’s esoteric vernacular photography collection; Tom Claxton of Webber Represents opens the lid on Laia Abril’s much celebrated The

Epilogue, at once a testimony and posthumous

biography of the life of Cammy Robinson, who died at 26 as a result of bulimia;

and David Moore discusses the merits

of Studio 54 by the great but somewhat under appreciated Tod Papageorge.

‘Brokeback Mountain’ Play Opens In London

LONDON (AP) — “Brokeback Mountain” was a star-making story onscreen. It may turn out to be the same onstage.

Rising American stars Lucas Hedges and Mike Faist are making their London theater debuts in an adaptation of Annie Proulx’s short story about two star-crossed Wyoming shepherds whose love is stifled by the strictures of their society.

Proulx’s tale of homophobia on the range, first published in 1997, reached a huge global audience through Ang Lee’s Academy Award-winning 2005 film, which cemented the stardom of Jake Gyllenhaal and the late Heath Ledger.

A new stage version at London’s Soho Place theater, stars Hedges as taciturn ranch hand Ennis Del Mar and Faist as livewire cowboy Jack Twist, who fall passionately in love during a 1960s summer on an isolated mountainside.

Both are already acclaimed young actors. Hedges got an Oscar nomination for playing a bereaved teenager in 2016 drama “Manchester by the Sea,” and Faist is a Tony Award nominee for “Dear Evan Hansen” and made a splash as gang leader Riff in Steven Spielberg’s “West Side Story.”

Still, Hedges admitted he was “pretty nervous” before opening night.

“It’s constantly a process of feeling like I’ve discovered the character and then losing the character and then finding it again,” Hedges told the Associated Press.

“We’re always nervous,” added Faist. But he said the actors trusted that director Jonathan Butterell had cast them for a reason.

David M. Benett via Getty Images

“It’s because he sees those qualities in us,” he said. “I think all of us in general have both of them. We’re all Ennises and we’re all Jacks, in our way. So the duality exists within all of us and part of our job is to just find those parts and bring them to the surface and make them the most accessible as possible.”

Ashley Robinson’s script aims to match the gut-wrenching economy of Proulx’s 35-page story. It covers two decades in 90 minutes, as the pair struggle to convert their passion into something sustainable and sustaining.

Hedges said the director had compared the show to the last production to run at Soho Place, Euripides’ Greek tragedy “Medea.”

“Of course it’s not ancient Greek theater, but there’s something deeply fundamental about it, about these two characters, about the way in which they need each other and can’t ultimately be together,” Hedges said. “There is something classic about the dynamic, and the stakes.”

The actors are accompanied onstage by a live band that includes Scottish singer Eddi Reader and legendary British pedal steel player B.J. Cole. But don’t call it a musical — this version of Wyoming is a long way from “Oklahoma!”

“These characters bursting into song would make no sense at all,” said Dan Gillespie Sells, who composed the show’s plaintive, country-tinged songs. “These characters don’t have an inner dialogue.

“They can’t express themselves, and they can’t express themselves to themselves.”

Instead, “a pedal steel guitar and a harmonica — those things can deliver you into landscape” both interior and exterior, said Sells, whose theater work includes songs for the musical “Everybody’s Talking About Jamie.”

“Brokeback Mountain,” which runs until Aug. 12, has drawn mixed reviews. The Guardian thought the play had a “distilled purity,” but the Times of London said the production “smolders fitfully” rather than catching fire. But there has been wide praise for the two leads, as well as for British actor Emily Fairn, making her professional stage debut as Ennis’s disappointed wife, Alma.

What’s undeniable is the power of the “Brokeback Mountain” story, which also was adapted into an opera, first staged in 2014, with music by Charles Wuorinen and libretto by Proulx. Some see it as a classic love story — but director Butterell thinks that is a misunderstanding.

“It’s not a love story,” he said. “It’s a story about fear. It’s a tragedy, because fear wins out.

“This story is still very, very, very relevant,” he added. “We have not shifted so far.”

Musicians like Jason Aldean love to glorify ‘small-town’ America. It’s embarrassing | Jill Filipovic

According to the country music star Jason Aldean, you’d better not use your first amendment rights in small-town America, unless you want to be attacked by a vigilante mob. That’s the message of Aldean’s controversial song Try That in a Small Town, which includes the lyrics, “Stomp on the flag and light it up / Yeah, you think you’re tough / Well, try that in a small town / See how far you make it down the road / Around here, we take care of our own” and “Full of good ol’ boys / raised up right / If you’re looking for a fight / Try that in a small town.”

Critics have pointed out that the song glorifies the kind of vigilante justice that has led to lynching and extra-judicial killings, and that the song feels like a very loosely veiled reference to Black Lives Matter protests. They also point to the conspiratorial thinking behind the line “Got a gun that my granddad gave me / They say one day they’re gonna round up / Well, that shit might fly in the city, good luck / Try that in a small town.”

Aldean and his supporters now claim he’s a victim of “cancel culture”.

The US supreme court has, notably, found that flag-burning is a protected first amendment activity. In my personal experience, city-dwellers are less interested in burning American flags than having the right to let our own freak flags fly. And there is no mainstream effort, from either the left or the right, to round up and confiscate firearms.

But setting aside Aldean’s apparent disregard for the constitution and reality itself, his message is unfortunately all too familiar. Small-town America – which is often code for conservative white America – is routinely treated as the “real America” by politicians, pundits, writers and culture-makers. Nearly all of those people choose to live in urban America, but cities don’t get the same kind of credit for being authentically American, or deeply good.

Aldean’s song is right, just not in the way he thinks it is: small-town America can be cruel, brutish and exclusionary. And cities are the United States’ beating hearts – they are places that make America great, and city-dwellers shouldn’t hesitate to defend them.

I have lived in, and truly loved living in, both the largest American city and an itty-bitty town. Small towns can be lovely places. What they aren’t, though, is inherently better than larger, more cosmopolitan locales. Small towns don’t have more of a claim to Americanism than the large urban areas in which most Americans actually live.

Part of the fetishization of small towns is fantasy and nostalgia. Small towns are symbols of imagined simplicity and moral goodness – life in a largely made-up “before” world when society was ostensibly less polarized, life was less complicated, and everyone lived in neat little single-family houses and gathered in church on Sundays. American life was, of course, never this simple, and always much more varied.

But politicians, pundits and culture-makers romanticize small-town life for the same reason they talk about the 1950s as an idealistic time, despite racial segregation, stifling gender roles and post-war trauma: it’s a comforting illusion, an invented history that suggests an ease and predictability most of us would love to feel.

“You are morally superior to these big-city folks” is also a convenient political message: it makes an important group of voters feel good about themselves (rural Americans, after all, have an outsized say at the ballot box), and I suspect it doesn’t really alienate city people because (a) we’re used to it, and (b) it’s so obviously untrue.

The truth is that cities are actually excellent places to live. Cities are the traditional hubs for immigrants, who routinely bring with them a tremendous work ethic and an entrepreneurship that drives the US economy and betters all of our lives. (Not to mention food – immigrants are a big part of the reason why cities like New York, Los Angeles, Houston and Chicago are such phenomenal places to eat.)

Cities tend to be racially diverse; the people who live in America’s biggest cities span a much wider range of religions and ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic levels than those who live in the country’s small towns. We hear a lot about “liberal bubbles” like New York or San Francisco when, in fact, it’s small, rural towns that are much more ethnically and ideologically homogeneous.

Cities are magnets for the ambitious, the creative, the young and the adventurous. The same politicians, pundits, journalists and musicians who extol the virtues of small towns rarely live in them. Aldean lives in Nashville.

And the diversity of cities also makes for more innovation. Human beings are more creative and generative when we are in diverse groups and interact with people who live, think and believe differently. Cities are fertile grounds for creativity to bloom.

They’re also offering more literal fertile ground. Globally, many cities are getting greener, and some American ones are following suit. Perhaps unexpectedly, life in a concrete jungle is better for the environment than rural life, and much better than life in suburban sprawl.

Cities also tend to be more liberal and more open-minded than smaller, more insular places, and that’s a good thing. A place where newcomers can try on new ways of being, and express themselves genuinely? That’s authenticity – not adhering to the narrow social codes that some small towns demand.

Contrary to perception, cities are also safer than rural areas by a variety of measures. Death rates are much higher in rural America than in urban America, by just about every cause, from heart disease to cancer to suicide to accidents (which includes overdoses and firearm and traffic accidents). Despite Aldean’s claims, small towns, it seems, are not doing all that great when it comes to taking care of their own.

And violent crime in urban America is frankly often fueled by conservative values: if the gun-snatching government bogeymen of Aldean’s paranoid fears were actually real, we’d live in a much safer nation. But the conservative demand that Americans have nearly unfettered access to deadly weapons means that a lot of Americans die unnecessarily – and a lot of those Americans are city-dwellers who have voted, again and again, for commonsense gun laws.

The idealization of small towns by politicians and culture-makers like Aldean also does a disservice to the places they claim to love. Rural America is not solely southern or midwestern; it is not entirely white; it is not universally conservative. Small towns are varied, and there is no singular way to live a small-town life. Most people who live in small towns are not “good ol’ boys”, gun-toting conspiracy theorists or vigilantes. Flattening small-town America into a stereotype is just as reductive as positioning cities as dens of crime and vice.

Cities shouldn’t need defending. Much of the country lives in them. They are the country’s economic, political, technological and artistic power centers. Most Americans, I would hope, can read the condescension and dishonesty in paeans to small-town life by people who have chosen to leave those very places in pursuit of cosmopolitanism, or never actually lived there in the first place. Aldean is from Macon, Georgia’s fourth-largest city.

But cities do need defending because, despite their popularity and obvious benefits, there’s little social cost to trashing them, or suggesting that the people who live in them are somehow less American. That has real consequences, including the hesitancy from our elected officials to make sure that every American has an equal say in the political process, and that “one person, one vote” is the reality of American democracy.

People should live where they like, and there are all kinds of benefits to both small, sweet towns and big, vibrant cities. Conservatives and liberals alike have not hesitated to sing the praises of small towns and small-town values, typically reducing those same places to a set of tired “real America” stereotypes. But it’s American cities that represent the best of American values: creativity, diversity and open arms to immigrants and innovators and all those looking for their people – and open to people who are different than them.

🩰 💫 🩰 The Royal Ballet School Summer Performance 2023 💫

Summer Performance

The Royal Opera House, London

Sunday, 16th July 2023

We open in a dream. Specifically, Don Quixote’s vision scene where he encounters an ensemble of fairies. Don Quixote was created for the Royal Ballet company by Carlos Acosta in 2013, and represents a challenging start for the students. They didn’t disappoint, tackling the classical steps with their signature sprezzatura.

The next two pieces – Fast Blue & Hora La Aninoasa – were accompanied by aurally strenuous music. Fast Blue is Mikaela Polley’s new work for the School, and is an energetic flashdance for 19 male Upper School students. Hora La Aninoasa, by Tom Bosma, brought traditional Romanian folk dances that suited the White Lodge students.

Kenneth Macmillan’s The Four Seasons breezed in with serenity, along with wafts of dancers clothed in beautiful pastel colours to match the mood. It’s very polite, gentle dancing with the students displaying an elegance that belies their years.

Last seen at the Summer Performance in 2015 and cloaking its classical challenges with a lot of fun (not an easy combo), Sechs Tänze by Jiří Kylián looks a lot like the ballet Manon but is more powder than swamp. Remember the excellence of Killian Smith & Grace Robinson ? Well, this year the casting didn’t disappoint either, with strong dancing/acting from the whole cast and standout performances from Seung Hee Han & Casper Lench. Ah, Casper Lench. The post-performance buzz in the auditorium was, “did you see Casper Lench in Takademe ?” Well, I did, and I will return to him shortly.

The beautifully Danish Konservatoriet, August Bournonville’s Vaudeville ballet looks fine on Aurora Chinchilla & Erle Østraat, set as it is in a ballet studio. White Lodge and Upper School students showed us elements of ballet class, with Ptolemy Gidney gently nudging things along.

Bold, by Goyo Montero, was devised for the Prix de Lausanne international ballet competition, and was danced here by the Upper School students. Jet black costumes, lots of running about, another dose of aural stimulation, with phenomenal talent from Rebecca Stewart; a dot of traffic on a busy stage.

What a treat to see the students in alumni Christopher Wheeldon’s Within The Golden Hour (Excerpts). Tawny gold costumes designed by Jasper Conran, burnishing the dancing to sparkling highlights. The pas de deux danced by graduating students (both to the Royal Ballet) Sierra Glasheen & Blake Smith was a subtle masterclass in partnering. The stylish ensemble sections saw Guillem Cabrera Espinach, Bethany Bartlett & Isabella Shaker shimmering over the stage.

Frederick Ashton’s The Two Pigeons pas de deux is once again a tricky bit of partnering. Without the actual two pigeons this time, Liya Fan & Tom Hazelby brought a gentle approach, well-matched to the choreography.

And so we arrive at the aforementioned Takademe. Caspar Lench has it all, and the Indian Kathak rhythms to a percussive score by Sheila Chandra only serve to highlight the breadth of his talent. The movement is punchy and speeds along in a panic of red trousers. It’s mesmerising to watch a dancer with the quiet confidence & sheer panache to dance solo on the Royal Opera House stage with measured assurance.

The Summer Performance always closes with the Grand Défilé; a dazzler of a full stop.

If you’d like to know where each of the 24 graduates are headed, you’ll find the complete list here.

Further photos from the Summer Performance photo shoot

kengo kuma blends tradition with contemporary elements for haus balma in vals, switzerland – Designboom

kengo kuma blends tradition with contemporary elements for haus balma in vals, switzerland Designboom

Source link

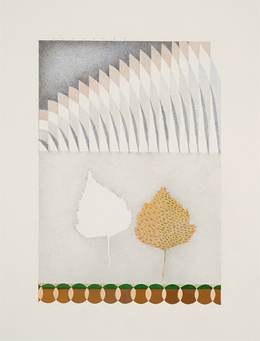

New York Art Reviews by John Haber

When a summer group show takes as its theme “Abstraction from Nature,” you can only wonder: how could no one have thought of this before? It makes that much sense. You may wonder, too, though, what so broad a theme could possibly leave out. With drawings like these, at McKenzie through August 18, the answers lie in the details. This is art from an active eye and hyperactive pencil, brush, or pen.

It is not just a cliché to compliment art after nature as approaching abstraction. I felt the urge just this month in Tribeca, as I noted last time, with JP Munro. It is just as common to speak of abstract art as abstracting away. With Susan Vecsey in Chelsea, at Berry Campbell through August 11, horizontal bands of close colors, often blue, hint at the horizon, sky, or sea. The gradual narrowing of one band is more suggestive still, of a road in linear perspective running alongside nature into depth. Back when, critics who disdained realism might make an exception for landscapes by Fairfield Porter—and, like Robert Rosenblum, find an antecedent to Abstract Expressionism in the Hudson River School and Northern Romantic tradition.

The New York School had no trouble leaving New York, at the very least in summer. Painters then could afford the Hamptons (and maybe a loft in Soho). The nine artists in “Abstraction from Nature” are not so lucky, but they still find nature everywhere they look, starting in the city. Abby Goldstein speaks of urban walks, Sarah Walker of collecting fallen leaves. Chris Arabadjis does his drawing on a two-hour commute. But then I run into fine flowers by Nancy Blum whenever I catch the subway, for she has tiled the nearest station.

When it comes to life in the subways, you may think first of germs. Arabadjis invokes instead tree rings, whirlpools, rock formations, and mycelia—the threads in fungi. If that sounds strange, they are all networks, tilings, or eddies. They are also rule-based, like his drawing. This Lower East Side gallery has a commitment to geometric abstraction, like that of Don Voisine, Gary Petersen, and more from past reviews than I can list here. Yet it also has a genuine fondness for surfaces, signs, and symbols.

That can mean obsessive patterning, of a kind that cannot help disrupting the pattern. Laura Sharp Wilson speaks of Defying a Brutal Art. It can lead to a search for optical activity as well, akin to Op Art, like Wilson in acrylic and Walker lending nature her electric color. Webs by Katia Santibañez seem to vibrate, as does paper itself for Marian Williams. Her pen adds a shimmering blue.

What they do not do is to hover between nature and abstraction. Almost everything here falls within one or the other. One will just have to take Santibañez at her word that her abstract webs look outward to spiders. Blum in fact produces two bodies of work for the show’s twin inspirations. Pencil weaves through her black paper or radiates outward. White clay butterflies hang high on the wall.

What they do not do is to hover between nature and abstraction. Almost everything here falls within one or the other. One will just have to take Santibañez at her word that her abstract webs look outward to spiders. Blum in fact produces two bodies of work for the show’s twin inspirations. Pencil weaves through her black paper or radiates outward. White clay butterflies hang high on the wall.

Their shared strength may lie less in the image, real or abstract, than in the artist’s hand. Jessica Deane Rosner could be denying both, with the appearance of collage in pencil, ink, and acrylic. Others, though, dedicate their work to the medium itself, like Katia Santibañez with her vibrations and Denise Sfraga with colored pencil. And that returns to a nagging question in art today. As painting proliferates and genres lose their meaning, what does that leave for abstract art? After all these years, the media may still be its message.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.

6 Ways to Be [Even] Happier About Running Your Art Business

I seem to have to remind students and clients how important their network is, and that they need to make a point of seeking collaborations.

I use the term collaboration broadly to refer to working with other people to advance your goals as an artist. Any. Other. People.

Seeking collaborative relationships is some of the highest level thinking I’ve witnessed in the thousands of artists I’ve encountered over the past 2 decades.. Artists who collaborate simply have more ambitious goals.

I’ll give you four quick examples from The Art Biz.

In episode 27, Jill Powers talked about how she collaborated with volunteers, chefs, scientists, venues, and more for a single exhibition.

In episode 86, Jerry McLaughlin and Rebecca Crowell discuss how they collaborate on a learning platform for artists.

In episode 126, Willie Cole reveals how he collaborates with top brands.

In episode 153, Danielle SeeWalker discusses a long-running photo and film documentary with a fellow artist.

All very different collaborations designed to help the artists fulfill their creative visions.

I know it can sometimes be frustrating working with other people, but the potential reward is too promising to overlook. As curator Melissa Messina said in episode 136, your network is everything.

Not only will you be happier when you collaborate, you will also stretch your business muscles and expand your audience when you bring more people in on what you’re doing.

That brings me to my next idea for how to be happier about running your art business.