New York Art Reviews by John Haber

Think keeping up with the news is hard? What about keeping up with the streets?

With “We Are Here,” the International Center of Photography exhibits “scenes from the streets,” through January 6, and its title is an assertion. It speaks for the show’s subjects, in sixteen countries, asserting their presence and demanding a voice. It speaks to the pace of the streets and the very nature of a photography, snapping away as best it can. We are here, it says, and soon we will be gone. What, though, will anyone remember? And what has happened to photography’s decisive moment?

Of course, Henri Cartier-Bresson coined “the decisive moment” to describe a vision of the present that not all photographers share—and I work this together with past reviews of Mark Steinmetz, Hans Breder, and Cartier-Bresson’s ideal as a longer review and my latest upload. Fashion photography or product photography needs time to create an image and to land a sale. Abstract photography asks to step out of time, even when it provides a window onto the photographer at work. From ICP’s founding, though, fifty years ago, it made photojournalism not a choice but a responsibility. It was not just keeping up with the news but making news. Lives were at stake.

Street photography can seem a casualty—or a foster child of silence and very fast time. You know what to expect at ICP, a city in motion. Look back to New York in the 1970s with Martha Cooper, when crime was at its peak, for empty lots and kids climbing the fences, if not the walls. Just crossing Canal Street with so many others is enough for Corky Lee. Skip ahead to the present, and collective motion means protest—for Freddie Gray in Baltimore with Devin Allen or for Women’s Day in Mexico City with Yolanda Andrade. Rest assured that the riot squad will turn up in force, even when no riot is going on.

Look for symbols, like the American flag put to personal use. Look for protest signs and graffiti, like spray paint that rechristens the American West for Nicholas Galanin as No Name Creek and Indian Land. Look for Palestinians on a day at the beach, Ferris wheels, kids doing cartwheels, or everyone just hanging out. Look for displays of street fashion, one girl or woman at a time. Look for them all again and again. The thirty-odd photographers get several shots apiece to do them justice. Most are contemporary and barely known.

The trouble is that you very much can expect them, over and over. Nothing seems all that decisive. As one protest sign has it, for Vanessa Charlot, the people demand “full humanity.” Actual humans, though, can get forgotten along the way, as older street photographers like Ming Smith and William Klein would never have allowed. The photographs do not want to make isolated, iconic images, which is exhilarating. Something, though, is lost—be it the issues at stake in protest, the poignancy of outcomes, or photography’s experiments.

There are things worth remembering nonetheless, on top of the sheer weight of the familiar. Street lives matter. While many stick to black and white, a tribute to street photography’s past, color can tell a story, too. It can erupt in umbrellas for Janette Beckman or women together, in South Africa for Trevor Stuurman or and in China for Feg Li. They are not just showing off but being themselves. Smugglers cycle or cart their bright bundles for Romuald Hazoumè, and yellow caps make police no less dangerous for Lam Yik Fei.

There are things worth remembering nonetheless, on top of the sheer weight of the familiar. Street lives matter. While many stick to black and white, a tribute to street photography’s past, color can tell a story, too. It can erupt in umbrellas for Janette Beckman or women together, in South Africa for Trevor Stuurman or and in China for Feg Li. They are not just showing off but being themselves. Smugglers cycle or cart their bright bundles for Romuald Hazoumè, and yellow caps make police no less dangerous for Lam Yik Fei.

Is a riot going on after all—a riot of color in the riot of the streets? Chastening to a critic, even the breaks in uniformity come more than once. I had admired Anthony Hernandez before for LA seen through a chain-link fence, but here the distancing comes again with Michael Wolf. Long exposures from Alexey Titarenko turn St. Petersburg into a city of ghosts. And then women in white at church in Nigeria for Stephen Tayo could be an extraterrestrial delegation for peace. This, too, is the street.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.

The Paris Review – Letters to James Schuyler

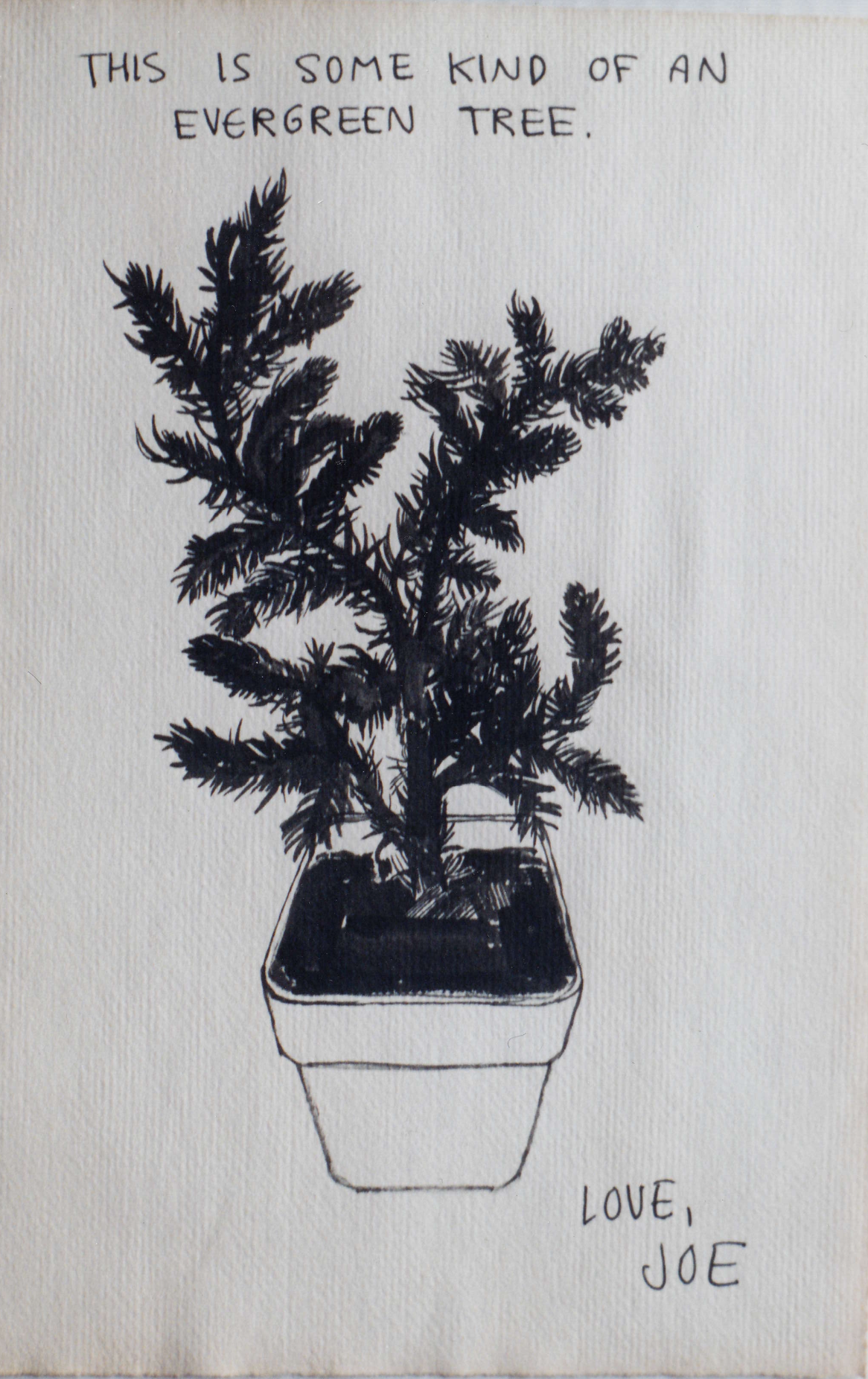

Excerpt from a Joe Brainard letter/booklet (“My New Plants”) to James Schuyler, December 1965, used by permission of The Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of the Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California-San Diego.

The artist and writer Joe Brainard and the poet James Schuyler, both central figures in the New York School of poets and painters, met in 1964. The two soon became close friends and confidants. Brainard’s letters to Schuyler included here span the summer of 1964 through 1969 and were written while Brainard was moving from apartment to apartment in New York City and spending summers in Southampton, Long Island, and Calais, Vermont.

You can read an interview between James Schuyler and the critic and poet Peter Schjeldahl in the new Fall issue of The Paris Review, no. 249, here. Schuyler and Schjeldahl were nominally meeting to discuss the poet Frank O’Hara, but the interview became a wide-ranging conversation about poetry, New York in the fifties, and the cast of characters that surrounded them.

August 1968

Southampton, Long Island

Dear Jimmy,

Wouldn’t you know it? My rose petals didn’t work out. Some of them were not dried enough when I put them into those small Welch’s grape juice bottles and so they mildewed and turned green. So I had to throw them all away. Now, however, I have begun sand bottles. (At night) I don’t waste my time with such stuff in the daytime. At any rate—I have many colors of sand now (food coloring) all in many dishes all waiting for tonight (everyone is leaving tonight) when I’m going to see if it works. I have seen beautiful ones with very intricate designs but for my first one I will only do stripes. A nice size, those Welch’s bottles. I don’t, however care for the juice. When Pat and Wayne [Padgett] were here they would drink it for me (and loved it) but now I’ve nobody. I had (just had) several days of bad painting (sloppy) but today was very good. Today was (is) the most beautiful day I can ever remember: very sunny and very cool. And very quiet: Sunday. Many Sundays seem somehow odd to me, but today was just perfect. I do love it here. It just doesn’t make sense to go back to the city. Except for people. That’s where so many of the best people are, to me. The phone is ringing but I am in the studio. Kenward is out watching the annual tennis tournaments. John and Scott are at the beach. John and John Scott (I don’t mean John and Scott, I mean John and John) are driving back tonight to the city. John to visit his mother for her seventy-fifth anniversary. I am talking of John Ashbery and John Scott, John’s new colored boy friend. I was afraid that perhaps you would get confused with John Button and Scott Burton. John and Scott, you may not know, have broken up. As I understand it tho, it was a mutual split. I am drinking a rosé wine. It’s about five o’clock. Once everyone gets back together we are going to an opening around the corner of Leon … (can’t remember). He is a very old romantic-realist and slick with lots of birds and fish nets. You know his work I am sure. Very much like Bernard. Morris Golde says that Fairfield [Porter]’s paintings looked terrific at the Biennale. He was very impressed with the number of them: said there were “lots.” I did some yellow pansies this morning with Fairfield’s yellow-black for green. I think that I would have done it anyway (?) but I always think of it as Fairfield’s thing: yellow-black for green. Actually, I have seen it in very few paintings that I have seen it in: one being the one I have. I hate to see today go. Will write more tomorrow, or soon—

Well—they didn’t leave around six as planned but instead we all (except Kenward) went to a queer beach party with Safronis [Sephronus Mundy] and Jack (know them?) Safronis is from Sodus, like John A[shbery]. At any rate, it got 40 degrees and so we didn’t go to the beach but instead to some terrible interior decorator’s place. His name is Jack. I have never (no exaggeration) met anyone so disgusting in my entire life. Also there was a beautiful Indian boy who has been after me for several years now. I must admit that he turns me on terrifically. There is something fishy tho as he is so beautiful he could do a lot better than me. He is the Gerard Malanga type but he really has what it takes to be that type. He may know him he is quite notorious: Tosh Carrillo. At any rate, I have come to regard him as somewhat of the devil. Anyway, it was upsetting seeing him last night. (Temptation) I think you know me well enough to know that I am rather liberal. I’ve had many affairs since I started going with Kenward and I don’t feel one ounce of guilt. But this Tosh guy, there is really something dangerous about him. I hope you don’t mind my telling you this. It shook me up so much to see him again as, of course, I’m very attracted to him too. I hope by telling you about it I can forget for a while. So—today is another beautiful day: cool and hot. There is (like yesterday) a bit of autumn in the air and yet the sun is shining very brightly. It’s really the best of both seasons and I love it. This morning I got up at seven and picked three pansies and put them into three small bottles. One yellow pansy, one red-purple and yellow, and one solid blue-purple. I did three paintings of them (all three in each) and I am sure that at least one of them will look good in the morning. They are not so loose as before. More like summer before last. When I finish writing you I am going to read “Le Petomane” (about a French farter) And tonight I planned to do my first sand bottle.

Oh—the opening yesterday was paintings by Leonid. They weren’t very good but I rather admired a very details [sic] : details painted with one or two strokes of the brush. Like birds. Gore Vidal was there he looked quite young (35–40). Today is the twelfth. That means we have about two more weeks.

Right? Some of your house plants don’t look too great. I think that at first I watered them too much. They are not dead tho. So far there hasn’t been any serious damage done. A chunk of black linoleum in the laundry room

came up. Too much water was left at various times on the wooden tops in the new kitchen part: a few black streaks in the wood. I am watching it carefully now. I’m going to get this in the mail now. Do write soon. Summer is almost over and winter will not write much. One thing I forgot to tell you is that

I use your bike. I love riding it and I knew that you would not mind. Did I tell you that we are going to give a cocktail party for Jane [Freilicher] for her opening? Not Sunday (the opening), but Saturday before.

Very much love,

Joe

P.S. Did you see our names in the Sunday Times?

About painter poet collaborations by Peter S.

June 1969

Calais, Vermont

Dear Jimmy__

Last night (how nice it is to be writing to you again) I made a real strawberry short cake. I found the recipe in a “Family Circle.” I must say it was awfully good. And very easy. Egg, butter, milk, flour, baking powder, salt, and bake for fifteen minutes. Today is my second day in Vermont and I love being here. I especially love being here because I know I will be here for ten weeks. What to do? That’s what I am thinking about now. Mainly I just want to paint but also I want to get my manuscript together and do an issue of “C” Comics. This is too much to do in ten weeks but I imagine that I will try. If I had any sense in my head I would just paint and forget everything else but I enjoy “everything else” so much that I find this hard to do. So—as usual—I am torn between this or that or both. And—also I will pick both. It is still a bit cool up here. I continually (so far) wear a sweater. This morning (actually, it is still morning) I wrote a bit on a new thing I am writing called “I Remember.” It is just a collection of things I remember. Example:

“I remember the first time I got a letter that said ‘after five days return to’ on the envelope, and I thought that I was supposed to return the letter to the sender after I had kept it for five days.”

Stuff like that. Some funny, some (I hope) interesting, and, some downright boring. These, however, I will probably cut out. Unfortunately, I don’t have a very good memory, so it’s a bit like pulling teeth. I’ve been eating lots. I weighed in at 140 lbs. and I plan to arrive in N.Y.C. weighing at least 150. I plan to do this by eating lots and:

– 2 glasses of milk with Ovaltine everyday

– 1 big spoon of honey everyday

– eat lots of nuts at night

– vitamin B-12 pill every morning

I might even cut down on my smoking, but I doubt it. I am afraid that I don’t really care that much. In Tulsa I picked up some old school photographs of me. Enclosed is one of me in 1951. I also got some old newspaper photos and clippings of me which are very funny and very embarrassing. I’ll send them to you soon but I would like to have them back. Do keep this photo tho, if you want it. I am tempted to draw a line and write more tomorrow but actually I would enjoy this being your first summer letter so I’m going to go ahead and mail it. Do write.

Love, Joe

July 4, 1969

Calais, Vermont

Dear Jimmy__

You can’t know how nice, really, it was to get your letter. You write such nice letters even when you have nothing in particular to say. I am outside sunbathing again, and so are Anne [Waldman] and Lewis [Warsh]. Kenward is at the cabin he is writing, but surely nobody writes that much. Yesterday I sorted out all my oils, lined them up according to colors and stretched two canvases: 18″ x 24″. I thought I would start painting today but the sky is so clear and the sun is so hot, and actually, I didn’t (don’t) especially feel like it: painting. So—perhaps tomorrow. But I refuse to rush myself. No reason to except nervous habit. And nervous habit only produces works like I’ve done before. Which doesn’t have much to do with “painting,” as I see it. Or as I think I see it. (I don’t know what I’m talking about) Anne and Lewis are terrific people to live with. Lewis (so far) remains just as mysterious, but in a friendly sort of way. Anne is just as nervous as me, which makes me feel not so nervous. We smoke a lot of “you know what.” Talk a lot. Eat a lot. Play cards some. (Pounce and Concentration) Did you ever play that? Concentration. I like it. If you don’t know how to play it, let me know, and I will explain it in my next letter. It’s very simple really. We read a bit every night from a “Woman’s Circle” or a “Woman’s Household” which reminds me: I want to send you some issues. Will soon. I don’t know how much I weigh now as we discovered that the scales are irregular. So—I am just eating a lot, altho it is not as much fun without being able to see (read) my gains. Next time we go into town, however, we are going to get a new pair. This I have never understood. Why scales are called a “pair.” Today is the 4th of July. Happy 4th! We here aren’t going to celebrate much, as far as I know, except that for dinner we are having a Harrington’s ham. There is a 4th of July parade today in East Calais, but I said “no thanks” to that, which put a damper on going. Nothing is more frightening to me than “Elks and Masons” and their children, etc. Besides, I don’t enjoy being an outsider. Did I tell you of a funny dream I had several nights ago? I don’t think so. At any rate—John Ashbery and I were chatting on my parent’s front porch and John said to me, “I think your Mondrian period was even better than Mondrian.” Actually, I never had a “Mondrian period” but in my dream I remember recalling the paintings I had done. They were just like Mondrian except with off-beat colors. Like slip [sic] peach and plum purple. Olive green. Etc. At any rate, I was awfully flattered. Frank O’Hara and J. J. Mitchell were there too, but I won’t go into that. Other people’s dreams are never as interesting as it seems they ought to be: to other people. Your advice is good. I do eat lots of nuts and I have been trying to eat as much as possible. Actually, getting better looking will probably only get me into more trouble, and make life more complicated. If I was wise I wouldn’t even try—but—once again—pardon the oil on this letter. It does help tho. And a warm shower afterwards. I am enclosing for you some “Button Face” note cards I sent away for from the “Woman’s Circle.” They’re very funny I think. Kenward and I have both been sending away for lots of stuff in order to get mail. Kenward has got lots of seeds. I got a “forget-me-not” necklace (“like grandma used to make”) which is somewhat of a disappointment. Also I got some crocheted butterflies which I gave to Kenward in celebration of the 1st day of July. They will be sewn on to curtains. I also got some “music post cards.” (Post cards with music on them) And some stars you glue to the ceiling and they glow in the dark. Like decals. I put them up in Anne and Lewis’s room and they like them. Someday it would be nice to do a whole ceiling. Also available is a friendly moon. I just went in for a Pepsi. It is now one o’clock. This afternoon I think I will get out my Polaroid and see what happens. Maybe we can swap pictures. Like those clubs do. Of a less intimate nature of course. In your next letter to me would you please sign your name (your autograph) on a piece of white paper. I am beginning to put together my poet’s scrapbook and your autograph would be a big boom [sic] (Or a drawing?) I have drawings already by Ron and Ted and Frank and Kenward. Also I have many photos and clippings and wedding announcements, etc. It will be a nice book that will never end. The sun is really very hot today. Now I am sunning my back. This will be my first all-round tan since I was a kid. Kenward is doing pretty well too, tho his skin doesn’t tan as fast as mine. Obviously I am running out of talk. Will stop now. Do write again when you feel like it.

Love, Joe

P.S. Anne and Lewis city news:

John Giorno and Jasper Johns are back together again.

Pat and Ron leave for Tulsa this Monday for one week. Then three weeks traveling around California.

John Wieners’ parents had him committed but a plan is being worked out to get him out.

Dial-A-Poem will be continued next year from the “St. Marks Church.”

Bill Berkson has moved. His new address is 107 E. 10th St.

D. D. Ryan has been promoted to assistant producer, and now, is actually in the movie.

That’s about it.

(again) Love, Joe

Mid-July 1969

Calais, Vermont

Dear Jimmy:

Flowers not going too well. All the different greens (which seem to change from moment to moment) are driving me up the wall. Also—there is a red-purple I just can’t get. Also my wild flowers are too curvy (Art-Nouveau) and I can’t seem to straighten them out. A line (stem) like this [draws a smooth upward curve] always seems to end up like this [draws an upward curve with kinks in it] and, when I try to straighten them out, they seem flat (life-less) not that I have anything against curves. But my flowers are practically flying out of their bottles, off the canvas, to god only knows where. I never have liked El Greco much. Except for one pope. So—I am not painting today. A break. I am sunning. Today is a beautiful clear day, very blue, with not a cloud in sight. The sun is hot. It is about one o’clock. Kenward is coming back from the city around seven tonight. The whole back of me is peeling, as one day it got too much sun. So—I will have to start all over, little by little, as for several years it has been totally neglected. (Sun-wise) Not much is new. Except that the day lilies are out. The orange ones. In full bloom. All over. There are many more of them this year. And the milkweeds. They are everywhere. Which is O.K. with me. I like them. I read somewhere the other day that during the war they were used for lining coats. (Their fibers, or something, make good insulation.) Army coats. For very cold weather. It also said that their very small top leaves (the top two or three), when cooked taste like asparagus. I would say they taste more like spinach. And not very good spinach at that. Perhaps we didn’t cook them right yesterday. After oil painting all morning (I got up at 5:30!) I picked some grass and did lots of green ink and brush drawings of it. I am now cutting the grass out (with an X-Acto knife) and then I am going to put it all together, in layers, to make a solid patch of grass. (11″ x 14″) So far I have cut out two layers. It is quite delicate cutting and I have a big blister to prove it. (Delicate, but hard) It will be very pretty I know. It can’t miss. And it’s a good thing to do (cutting out grass) around four or five o’clock when your head is tired but you are still sort of wound up. Just before a drink. I plan to do a fern one too. If we ever get to Burlington (to get some more X-Acto blades). As it is rather intricate cutting one blade will not cut very much so finely. I could always send to the city for some. (Mail!) Now I am not sure what to do about my two oil paintings of two wild flowers arrangements. The actual flowers are gone now so I have a choice of “faking it” (which I am very good at) or forgetting them and start some new ones. I think I will do this (start some new paintings) as, if I’m going to fake it, I may as well wait until I get back to the city. Meanwhile, perhaps I can do some direct, here. I must keep reminding myself that this is not my purpose, now, to “produce good paintings” (rather to learn) about oils. About how things look. About color. Etc. Color is a real problem. I don’t know the tube colors so well as I know tempera jar colors. So I have to think. And thinking isn’t much good when it comes to color. From tempera painting I remember the best “right” colors more or less just happen. Do you know anything about toe nails? My right foot is bigger than my left foot and cowboy boots are not very good for you, but I wore them a lot last year anyway. The result is that my big toe nail is so squeezed together and it is very thick and sort of yellow. My idea is to file the entire nail (the top half, actually) down to how thin it ought to be. Do you think this would hurt? (The nail) That is to say, is a nail the same all the way through? I would hate to file away the surface of the nail and find something different underneath it. There are several health books here, all with toe nail sections, but you know how health books are. (No real information) They are cutting down some trees off to the left. (If one was entering the front door) So for days there has been constant sawing. What we hear, I guess, is like an echo. Like a car trying to start. One does get used to it tho. Mrs. [Louise Andrews] Kent’s son owns that land. Aside from getting lots of wood, it is supposed to be good for the land. (Thinning it) So Kenward said. So Ralph [Weeks] told Kenward Mrs. Kent is in the hospital. I don’t know if you know her well enough that you would want to send a card or not. I don’t know exactly what is wrong with her except that, really, she is very old. It is the Montpelier Hospital. The one Ron was in. Pat and Ron are either in Tulsa, or on their way to California. Or perhaps in California. It’s hard to keep track of the date up here. And I don’t know their plans anyway. (Date-wise) Sometime in August they will come up here next to visit some. Unless, by next year we are not very close. Which is possible. Actually we weren’t terribly close this year. Old friends don’t want you to change. And, of course, it works both ways. Or, perhaps it is just harder, around old friends, to try to change. At any rate—sometimes, around Pat and Ron (and especially Ted) I don’t feel like myself. (1969-wise) Of course, there are compensations. Like—I always feel very comfortable around Pat and Ron. And that’s NICE. I’m going to sign off before I find myself with a whole new page to fill. There has been no mail for two days as Kenward has been away. So—if I have received a letter from you and not mentioned it, this is why I haven’t received it. Do write.

Love, Joe

P.S. Actually, Ron is trying. Two times last year I got a kiss. And after seeing the Royal Ballet he said that Nureyev has a rear end like mine. For some reason I was very touched by that. (Wish it were true).

From Love, Joe: The Collected Letters of Joe Brainard, edited by Daniel Kane, to be published by Columbia University Press this November.

Joe Brainard (1942–1994) was raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and moved to New York City in 1960. He was a prolific writer and artist across many media, including paintings, collages, assemblages, and comic-strip collaborations with poets. His I Remember has been translated into fifteen languages, and his artworks are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and many others. He died of AIDS-related pneumonia.

The intensely felt art of Elisabeth Frink

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Elisabeth Frink said that her sculptures are ‘about what a human being or animal feels like, not what they necessarily look like’. This quotation appears on the wall of a new exhibition of her work in the Weston Gallery of Yorkshire Sculpture Park. In the centre of the room are four monumental heads that dominate the space, but when I visited my eye was drawn to a small cluster of her earlier works from the 1950s and ’60s. These are tortured, desiccated forms, seemingly in a state of decay. They have an anthropomorphic quality – Vulture (c. 1952), for instance, is hunched and human-like, while Cat (1953) is an unsettling work; the body of the cat is contorted as if in pain, its face is arrestingly half-human, with enlarged, open eyes and an unfeline mouth like a letterbox. If Frink’s work is about what it feels like to be one of these creatures, we can only wonder what torment they have suffered.

It’s tempting to think that these sculptures, created in the decade after the end of the Second World War, are the work of an artist for whom the collective trauma of conflict was still fresh. This was, of course, the period in which a group of young British sculptors, including Lynn Chadwick and Eduardo Paolozzi, came to be labelled the ‘Geometry of Fear’ school. Frink was younger than these artists, but there is a noticeable difference between the work she made in the years after the war and the gentler, more pedestrian forms of the middle part of her career, such as Dog II (1980), a life-like, somewhat anodyne sculpture of a Vizsla.

Cat (1953), Elisabeth Frink. Photo: Jonty Wilde; courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Frink made her pieces by building up plaster on a wire armature and then working it with a chisel – or in some cases an axe – once it was dry. The finished piece was then cast in bronze. In the earlier forms, the bronze holds the shapes of sticky clumps of plaster and in places is hacked and scored. Later on, the work is often smoother, with a softer silhouette. As a way of working, this practice is both constructive and destructive – about the drama of presence and absence; layering material, but also hewing away at it, risking the loss of previously worked shapes and forms.

Frink is perhaps most famous as a sculptor interested in raw masculine strength, in brutality and in power, but a less well-known aspect of her oeuvre is the narrative work, much of it on paper. In etchings and screenprints, Frink took on the tangled webs of mythology, folklore and English literature, as in The Canterbury Tales (1972) – her first etchings – and the Children of the Gods series (1988). The female body is rare in her work (I’ve yet to see a three-dimensional female form in her corpus), but when pushed by the demands of a narrative, Frink did occasionally depict women. It’s wonderful, then, to see her etching and aquatint of Hades and Persephone (1988) in the exhibition. The image is dominated by the horse drawing Hades’ chariot. In the upper part of the composition is Hades, his eyes blacked out, recalling Frink’s famous series of sculptures of men with goggles. He holds the naked, fragile form of Persephone like a rag doll. Frink is at her most unsettling when depicting the power imbalances between men and women. Persephone is helpless, as the god of the underworld thunders back to his realm holding her in his clutches.

Ganymede (1988), Elisabeth Frink. Photo: © Frink Estate; courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park

One of the joys of this exhibition is the way it presents work from different points in Frink’s career, across different media. We can see the breadth of her interests, from images of animals and insects, such as Carapace II (1963) to works on Christian religious themes, alongside figures from legend and history. Indeed, it is a striking feature of her work that she was so open to stories from such differing traditions. The show was put together from a large bequest to Yorkshire Sculpture Park from the artist’s late son, Lin Jammet. The exhibition in the Weston Gallery is accompanied by a display of Frink’s characteristic bronzes outside in the park itself. These are the life-size male figures for which Frink is most famous. Protomartyr (1976) has slender limbs, the figure’s arms half raised as he reaches his face skyward, his eyes closed in beatific calm. It is Saint Stephen who is often called the protomartyr or first martyr of Christianity (he died in c. AD 34). He is frequently depicted with a clutch of stones, alluding to his death by stoning. Nothing about this figure by Frink, however, suggests Stephen’s martyrdom. What did it feel like to be the first martyr? Transcendental, Frink seems to say. There is a marked difference between this work and Judas (1963), made more than 13 years earlier. While Protomartyr is smooth and sleek, Judas is clumpy and half-formed, with bulky shoulders and spindly legs. His head is helmet-like; his eyes are covered. Here – as in other works – figures with obscured eyes seem to symbolise some kind of ethical blindness.

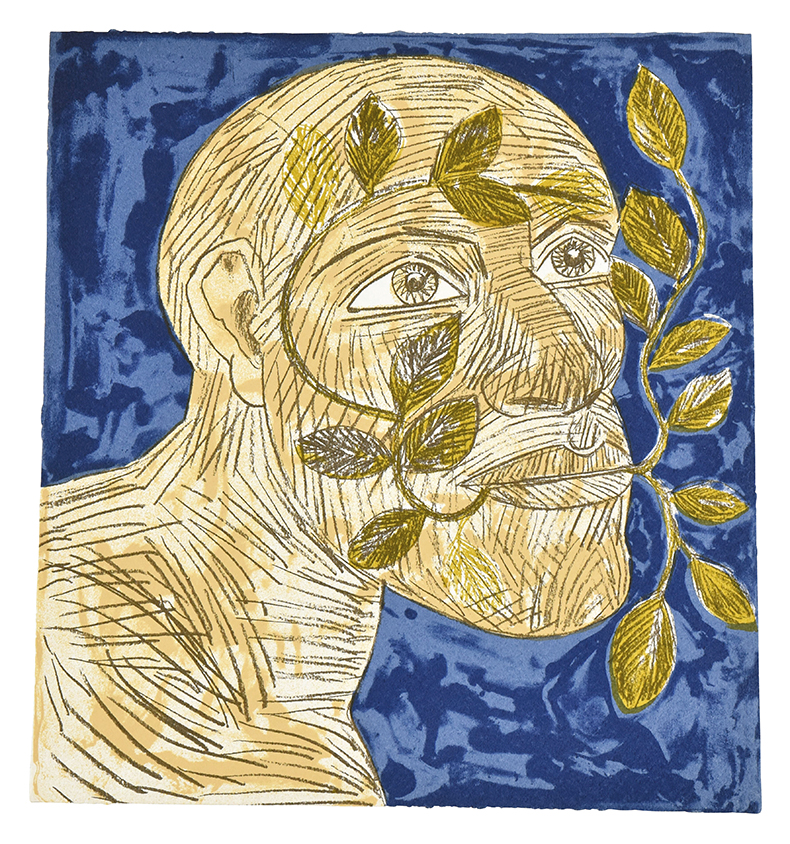

On my way home, I kept thinking about a plaster work called Green Man (1991) in the Weston Gallery. It’s a haunting piece, created after Frink had been diagnosed with a terminal illness. The Green Man, or the Woodwose, is an ancient English folkloric symbol of nature, fertility and renewal. Appearing carved into misericords and as a heraldic motif, and often composed of leaves, he is a creature of the woods, a bringer of chaos but also hope. Outwardly the form at Yorkshire Sculpture Park looks like a familiar Frink figure – big eyes, heavy chin, bald head. But up close, in the white plaster, you can see tendrils of greenery growing from his mouth and up over his head. This Green Man also appears in two screen prints from 1992. In both images the men cast their eyes towards the sky. The series was to be Frink’s last; she died in April 1993. In her final works, Frink reached back into the distant past to create images filled with quiet promise.

Green Man (blue) (1992), Elisabeth Frink. Photo: © Frink Estate; courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park

‘Elisabeth Frink: Natural Connection’ is at Yorkshire Sculpture Park until 23 February 2025.

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Precious Lives and Precious Things

A wall lay in ruins, and Ilit Azoulay salvaged what she could. It must have been a tough choice of what to save and what to let go.

For Azoulay, trash can itself be precious, for it tells of the people who left it behind. And anything, no matter how revered and how precious, could one day soon end up in the trash. As the Jewish Museum has it, they are “Mere Things,” through January 5— and I work this together wish a past report on still life with thoughts of death by Rachael Catharine Anderson as a longer review and my latest upload.

and I work this together wish a past report on still life with thoughts of death by Rachael Catharine Anderson as a longer review and my latest upload.

Those ruins from Tel Aviv form the basis of Tree for Too One, as in (almost) “two for one” and “Tea for Two.” You can forgive Azoulay an easy pun and the old soft shoe. She puts things through a process very much like punning, which is to say art. It takes a museum wall to display them all, some on shelves and others transformed again by photographing them, before displaying the photos, too. This is both physical collage and photocollage, and it leans a magnifying class on one its pieces—to aid in looking or to put under scrutiny what she sees. Earth tones help unify the work and preserve its warmth.

Just how precious, though, is it? Azoulay is not saying, but a gasket can look like a wedding ring, and a tree (or whatever is left of it) grows right there, in a flower pot—falling to its right toward death. More objects rest in a display case a few feet away. That strangely human wish for meaning does the transforming, but so do snapshots salvaged from the site. They look all the more poignant for their bright smiles and clumsy prints, set amid a sophisticated work of photography. People, too, can become objects and images, but as testimony to lives.

This is not NIMBY—not a protest against construction in the country’s most cosmopolitan city. A pressing need for housing dates back even before the international accord that promised a state of Israel and a Palestinian state. Refugees to Israel knew all about displacement, much like art. Builders were so desperate, the museum explains, that they built walls from whatever lay at hand. And yes, that was another way of valuing and preserving trash. Azoulay need only reveal what walls once hid.

Museums go through a similar process of deciding what to value every day. No surprise then, if the rest of work since 2010 responds to museum collections. None is exactly site specific, because it is also continuing its transformations. Again and again, she seeks parallels among disparate objects, like a piper and a stone saint. A photocollage makes objects from the Jewish Museum itself take flight, as Unity Totem. Azoulay produced her most massive work while in residence at a museum in Berlin, where she lives.  As the title has it, there are Shifting Degrees of Certainty.

As the title has it, there are Shifting Degrees of Certainty.

Two more works start with photographs of objects in the Israel Museum and the Museum for Islamic Art, both in Jerusalem. No surprise there, too—not when Israel still seeks safety and Palestine its due recognition. No surprise as well if the first includes HVAC units and other museum infrastructure. That work includes a collage of human cutouts and stone, while fragments of Arab art become a magician’s robe. Once again people are the most precious object of all. As the work after the Israel Museum has it, No Thing Dies.

The curator, Shira Backer, stresses how much the artist relies on digital magic. “A pebble becomes a boulder, the handle of a ewer the scepter of a queen.” I was struck instead by the weight of images—not just the emotional weight, but the physical weight of museum objects. The eighty-five photos from Berlin have distinct shapes and separate frames, nesting together like a single precious structure. Born in Israel in 1972, she keeps returning to both her origins and Berlin. The work provides a tour of physical space as well.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.

The Paris Review – Dreaming Within the Text: Notebooks on Herman Melville

From Six Drawings by Robert Horvitz, a portfolio published by The Paris Review in 1978.

The following entries came from notebooks the writer and psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas kept between 1974 and 1977. These notebooks were not written or edited for publication–Bollas says they were more like “mental scratch pads where the author simply writes out what he is thinking in the moment without, ironically, thinking about it.” The entries touch on things Bollas was reading at the time, scenes he saw in London, what he was observing in patients–and, more often than not, the ways these all intersected in his thoughts. We selected these entries in part because they cover a period of time when he was reading and thinking on and off about the work of Herman Melville, alongside many other questions about character, the self, and others.

Undated entry, 1974

Let us imagine that all neuroses and psychoses are the self’s way of speaking the unspeakable. The task of analysis is to provide an ambience in which the neurotic or characterological speech can be spoken to the analyst and understood. It is not so much [a question of] what are the epistemologies of each disorder but what does psychoanalytical treatment tell us about them? We must conclude that it tells us that all conflict is flight from the object and that analysis restores the structure of a relation so that the patient can engage in a dialogue with the object.

The style of the obsessive-compulsive, for example, is in the nature of a closed cognitive and active world. If obsessive-compulsive behavior is memory, what is being recalled? It seems to me that obsessive-compulsive behavior is a mimetic caricature of rigid mothering. It is caricatured self-mothering which [may] recall [interpret] the mother’s handling of the child.

How else can we account for the shifts in disorders if we don’t take into account the paradigms which generate them? Insofar as we know that patterns of mothering vary historically, can’t we assume that each disorder remembers the primary object relation? Indeed, why else does psychoanalysis go back to childhood when presented with conflict? Because it is understood by most to be functionally derivative of infancy.

The only problem is that the philosophical assumptions of this hypothesis remain unappreciated, to wit, all disorders speak the individual’s past and they ultimately speak the subject’s interpretation of the past and therefore are a form of remembering. The advantage of this to the person is to value his disorder as a statement, not simply a dysfunction. This is the difference between the hermeneutic and functional traditions of psychoanalysis.

A symptom is a way of thinking. Remembering is a way of thinking. Symptoms are some form of the subject’s thinking about himself. Psychoanalysis is a way of two people thinking together about one person’s thinking.

A patient brings a mood, thought, confusion, a blank—collages of himself—and the analyst provides the space. The therapeutic alliance is simply: we are thinking and working together. The transference and countertransference: we are feeling for each other together.

Undated, 1974

“American literature”

American writers speak the true self, while the country doesn’t listen. Melville tries to identify with this American false self—the external explorer and conqueror—but fails and the true self breaks through.

Undated, 1974

“Ahab”

What is absolutely essential is to keep in mind that Moby Dick is an invention, a projected object. The horrid irony of Ahab’s effort to break through the “pasteboard mask” is that he is the object behind the mask! He is the originating subjectivity. Does Melville make this irony specific?

The five phantoms loosed in chapter 47 are the loosening of Ahab’s internal objects: or the objectivization of internal selves. Rage permits the dissociations to be loosed though never integrated. Rage—especially in the search for the whale—is a loosening of or an exorcism of internal objects. The whole point of the trip is to exorcise the phantoms and to put them into the whale.

Undated, 1975

It is one of the ironies of existence that you can love the other only after you have lost the other. With ego development the fusion with the other is lost, a necessary precondition for recognizing the other’s separateness, but nonetheless a losing of one’s [fused] self.

Undated, 1975

“Melville’s ethics”

At a time when the other is sought outside, as a deity, an idea, or history, Melville’s hero points toward the struggle to find other as the unconscious self. In a sense as man has destroyed culture (collective dream/play space) he then assumes the responsibility of it and comes to a point of wisdom: culture always reflected him; he created it, it came from him. The sacred, profane, shared, etc., all experienced as outside; Melville says we must experience an inside other.

Thus he has in Mardi and in Moby-Dick a transitional metaphysical and psychical moment between other as outside (the whale) while Melville gently proves it to be inside the self. It is important to see this as Melville’s ethic. Outside, there is neither solution nor absolution; nor is either ever possible. Insight, the seeing into the self, to witness and behold the other as inside is the shock of re-cognition that Melville asks of us. It is the venue of the psychoanalyst as well, but the psychoanalyst after Freud’s metapsychological works processed the other and ethically disowned it.

Free association, which was a way of access, against the resistance of man, became a means of disowning the other by processing it. A novelist like Melville searches inside himself, comes to the point of seeing and holds the fundamental fact of the internal other.

December 10, 1975

“On good interpretation as poetry”

It is the form of an interpretation that is most effective. We must know that our best interpretations are poetic in their structure and delivery, so that the form holds words in such a way as to deeply affect the patient. In the same way, poetry rather than prose gets to us in a deeper way.

January 22, 1976

Out of the debris of our dying culture (early twentieth century) comes a new mythology and a new language. We see this early in Baudelaire who finds the symbolic inside the city; we discover it in Barthes (Mythologies) who creates a new mythology. It is godless. It is ordinary. As Barrett points out in Irrational Man, cubism is the ontologizing of the banal object, because out of the debris only objects are left.

The psychoanalytical experience is, in free association, the use of the ordinary (i.e., trivial language) to remythologize the person, to find his myth, his culture, through the debris. From the debris of his own words, which up till now he has found barren, a wasteland, he discovers meaning and then his own myth.

The analyst is the person, par excellence, who carries the person through the wasteland of the self, and who holds.

Where has the debris come from?

From an explosion in the nineteenth century of human value and belief. We are commodities, objects-to-ourselves, defined by use or function.

The death of culture. Debris. Playing with debris (Dadaism). Creating a new language.

The analytic process: death of the old self; debris and the sense of dislocation; playing with the debris; searching in anger, despair; through reflection, finding one’s self.

Barrett says that before man is a being, he is a “being-in” (111): taking Heidegger’s point about Being in the World. In modern man this Being in, or the essence of our being, has been lost. It can be re-found in psychoanalysis.

In Coleridge’s “Dejection: An Ode” and in Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts we see man expressing his sense of loss of being-in the actual world. We have seen this earlier with Pascal, though in his situation it was as much the losing of a spiritual world: being in a world of spirit. Being-in spiritually (mythically) and Being-in actually (materially) have been severed. It is this loss which writes the “Wasteland” and founds existentialism.

Out of this comes man and world as debris, cut up in Dada and Joyce, and now a new myth of man emerges. What is the new man?

The silence of the patient comes after despair over the word. They have said, perhaps, a great deal, but begin to have a feeling of despair over the word. This despair sponsors a silence; it is silence in the face of the unthinkable; the absence in the core of a person over a truly spontaneous sense of being-in the world. Their speech has been a narrative account, a construction, often beautifully or bravely rendered.

The patient of today can speak only for so long. Speech is an effort. It is an attempt to hold off the void. (Pascal.) The silence denotes emptiness and the absence of the other. The analyst must be absence coming eventually into presence through holding.

We focus on the mother as the cause, but in fact, she is all that is left of one who gives meaning, breathes life into the other, and so we focus on her. She can never make up for the void in the culture. Our search into this relation, solely, is a misdirected one.

Character and creation. Our being does have voice through character. To hear it is a task, painful, awful. It is the voice of our emptiness yet through the transference—the analytic paradigm—our character changes.

In Moby-Dick the myth explodes (capitalism, Protestantism). We are left with Bartleby, mute among the debris—dead letters. The Confidence-Man remythologizes by manipulating the ordinary into the fantastic. He picks up debris and maps the fantastic.

After 1914 man learns, according to William Barrett, that the solitude of being a self is irreducible regardless of how completely we seem to be part of a social milieu. Man is no longer contained in a social fabric. But with our patients the tragedy is that each must fashion a life out of a wasteland.

In the sixties, politics, group movements, the therapies, communes, etc., were all attempts to fashion cultures. The Beatniks (Kerouac, etc.) were the first.

It is silly to say “counterculture” as there was no culture there in the first place.

Each of us carries within our own debris. It is our past: a past not held within a familial, social, and cultural container to be given recurrently back to us. We don’t know our past. We only have images, memories, pictures etc. We bring this flotsam to the analyst who gathers the pieces; he gives form to our content—if we can trust him to do this—we find our past. This is the analyst as the transformational object: the one who gives form to our content and thereby transforms the content itself, by giving it meaning.

Out of the debris of our past emerges our own mythology. Why have I been so moved when on one bright day I witnessed from a 10,000-ft. peak of the Sierra Madre a tiny train thousands of feet below crossing the California desert? Why should this experience be so close to me, seem to hold me? It was a question, in fact, that I had never asked at the time. Its essence evaporated into the diversions of my life, though now and then I recovered it.

In analysis I found two things about myself. One was that, as my father had gone off to war when I was three months I did not see him until I was nearly two. I was overly eager not to see my mother disappear as well. At nursery school, it was my fate to stand up high on the steps of the slide—not to go down—in order to watch in the distance for the first sight of my mother who would come to collect me.

So being up high and searching for something vital and joyful was part of my personal idiom: the creation of my myth of significance and order.

The other mythical object was the train, which has always filled me with sadness and, strangely, contentment at the same time. So it was in my analysis that I discovered that it was by train that I left my birthplace and my father and also it was to the train station that every day my grandfather took me to see the train go by. Perhaps he did it out of his own love of trains or perhaps it was because I indicated my desire to see trains and he, in kindness, facilitated this wish. What the myth of trains gave to me in analysis, with the understanding of the essence of the aesthetic experience on the mountaintop, was how an experience visualised for me a deep myth: searching for recovery from my mother, longing to be reunited with my father. The experience of looking on the mountaintop was me.

May 9, 1976

“Metaphysical psychology”

Is it the eventual affirmation of the negative? Is Moby-Dick an affirmation of brotherhood, through the destruction of isolated fanaticisms? Ishmael lives to share a narrative with others, unifying men through discourse, while Ahab uses men to fulfill the fantastic demands of his private culture.

November 4, 1976

“On a character serving in a restaurant”

I am watching a young woman who is the waitress (wife) in an artificially lit Italian café that serves sandwiches to the English. The surroundings are without character, rather like the set of a television film, suggesting its impermanence. There is little here, except the come and go. The first time I ate here, she paid me no attention—flung the food on the table. Yet, tonight, I have discovered her use of herself as a character. She dissociates from the surroundings, defying the anomie by being a character. She throws her hands through her hair, punches out the orders, laughs or teases the locals—yet she is totally self contained. I find this interesting as I am reminded of Marx’s theory of alienation. She deals with it all by laboring her character: it becomes the surrounding of the self, and she looks no further.

Undated, 1977

“The text dreaming”

The text would have to undergo an experience of its own dream. Like the dreamer, the text would have to be confused. It is not simply the author who has the dream as the dream elements are already in the text at hand. With Stubb’s dream I must see what holds up to the dream and then what occurs after the dream.

The point is to establish the composition of the dream space, in literature or in life. It is an area of

1. Wonder or terror

2. Actualization

3. Enigmatic meaning

4. The place where the thinker is the thought of himself, or, the thinker the participant in the thought

The dream in literature must be a region of wonder, separate from yet reflexive to the rest of the text. It must be the dream’s text, as it must use and pit itself against the text, in order for us to consider it as a dream. A space in relation to the context of events in the fiction. Is it an allegory within an allegory?

What is the difference between a vision and a dream?

I am concerned with a text which has a dream, a moment when the continuity of its presence of mind is interrupted by a dissociation in its consciousness, in a space that I have called the dream space. The text can have its own dream if at this moment the cumulative experience of imagery-making, of plot construction, of characterization, breaks down into a self-reflexive dream process. This is rather like a breakdown, but a breakdown of a very special kind. In such moments the author yields, under the demand of the text’s unconscious logic, to the text’s (and his) need to share a dream with each other. (So, the author shares a dream with his text!) We could say that this moment will be more available in the modern novel, where the author already has found an intimacy of rapport with the text, where he uses more the idioms of his own internal psychic structures than the conventions of literary creativity. Even so, few authors—as Poulet insists—achieve a level of sincerity toward their own text. I should say, an intimacy where the text is the container of unintegrated subjectivity, and where the author’s Other is not an alienated moi, but a subjective object.

To the person writing or dreaming, writing (or textualization) and dreaming are processes of thinking about being, not products. We must, as E. Said argues, reacquaint ourselves with writing as a process, not a finished product.

This can also happen because an author, like Melville, needs to dream within the text; though the experience of the dream will be in the textual space, will use the history of the text for the dream material, and, as such, will be the text’s dream. If an author, like Melville, yields himself to the text, then we can say that the text will dream him, or dream about him.

April 26, 1977

“Melville”

The core fantasy seems to be of a desire for an object to be plundered. In Moby-Dick this was the whale, but this leads to annihilation. In “Bartleby” there is a desire for the experience to be provided by the other (the employer), with a dead ending in the brick-wall prison. In “I and My Chimney” there is an attachment to the object as inanimate and under the fantasy control of the self.

What can we call this cluster? It is a private phantasy: an autistic phantasy that materializes within the fiction, but isn’t made explicit as such. In “Bartleby” it is addressed to the other. In Pierre what do we make of the episode when the character crawls under the rock, to be born again? Is that another cluster? Is the fictional space a place where Melville can have this phantasy? An autistic voice?

May 2, 1977

“Melville”

Literary perversion.

Idiot event.

Burlesque.

Are there certain fantasies of the text that are not thoughts per se but ritual enactments of ego structures? Deep memories, paradigms, of the subject’s experience of the other?

Is an allegorical personification a character? Insofar as this structure speaks structurally, it is.

The idiomatic arrangement of character structures is the voice of character: the interpretation of self.

Does character speak in fiction more uniquely as the other becomes a phantom (death of God) eliciting a mute yell from the subject—as the voice of character? All character is utterance to an absent other, and with the death of God, this absence provokes deep language cries.

In some characterizations—especially sagas—we must ask, What is left out? The character may be noble, set against a surrounding world that is very violent. This is the split-off voice of character, which in the nineteenth century is joined to the self. Character defends the self against the internal world.

How does character relate—i.e., to us, the objects around it? Such use, does it reveal idioms?

The absence of a specific character language, particularly the person who seems to be strong and induces our projective identifications, creates a dream space for us. Character is the container of the reading subject’s pure self. We are Other.

May 3, 1977

“Character in fiction”

Does character in fiction depend on what the hero deals with or transforms? Where are the events of being? Character has to do with the idiom of transformation: an interpretation of the self. Where is the locus of transformation in fiction: in the author, or, is it yielded over to character?

What is the relation of character to the author’s use of character?

Character in fiction is a type of speech which may or may not occur in fiction. It is an interpretation of the self. If it is only a rhetorical device, it will only be interpreting the self as a rhetorical act. However, if the self experiences an internal world and relating, then character speech may occur as a reading of that self.

Rhetorical versus psychological character.

How do we experience the character in fiction? Or, how do others [other characters in a novel] experience the character in fiction? He is set up in others and in the reader. Is the text, the Other for the character? Does it reply to him or hold him?

Does character reflect the mental process of the text? Is character an interpretation of being inside the text? Where text is the psychical process, does character interpret this?

Undated, 1977

“Character”

Character in a text expresses something. Invariably, it is the discourse of structure, of handling by a self, and is a different hermeneutic. A character may say “I love you” but the formality of his being may say “Only at a safe distance do I love you.” This speech is the discourse of character and is a subjective interpretation of the self rather than the professed themes uttered by the subject. Think of Heidegger’s notion of the existence-structure of the self. Ishmael and Ahab transform the subject “I will hunt the whale” in different ways. Their style of handling is an interpretation of the self. It will speak fundamental paradigms of transformation of need, desire, fear, etc., of instincts and relating to the object. When an author releases different characters into fiction he is releasing varying ego structures in himself, different selves, to personify aesthetics of being.

“The Aesthetics of Being: Character as Discourse on the Self.”

We cannot decenter character from the crucial reality that there is an interpretive presence in character. The structures of character are idiomatic internalisations of self-object (and self as instinctual presence as object) relations. These are matters of choice. Ishmael and Ahab make choices derived from their different ego structures.

By releasing character the author uses different styles of transformation of desire and relating to the other.

In fiction, each character embodies a character memory.

Does any of it have to do with the experience of the text? In the sense that an author may release his internal world into the text, characters are different modes (ego structures) of handling and interpreting these themes. This handling (transformation) is the aesthetic of character.

Ego structure. The infant experiences the mother. On the basis of the infant’s experience of the mother he makes choices about handling the mother.

In Moby-Dick Melville puts one ill and one healthy ego structure alongside one another, in the juxtaposition of Ahab and Ishmael.

The mother’s handling of her infant is an aesthetic and points the way to her notion of the baby’s body and self. Her handling complements the baby’s emergent ego (handling) functions. As the mother handles instinct and impulse, so the baby internalizes her paradigms. This is the internalization of an interpretation of the self.

Undated, 1977

“Metaphor as secret”

Metaphor takes a word which applies to one thing and transfers it to another because it seems a natural transfer. This occurs in Melville’s pyramid fantasies where clusters of metaphor sequester hidden meanings. The chimney has hidden spaces and is a metaphor of secret places. Such an act is at the root of fiction. Keeping the source a secret, yet communicating from it. Is it some deep ego structure that finds symbolic equations for itself?

Undated, 1977

“Character versus subjectivity”

Character is memory. It is an aesthetic of being that forms and transforms experience according to an unconscious hermeneutic. It is mute in the sense that the receiver is absent (except in analysis) and the subject who enacts his character is blind and deaf to his aesthetic.

In a sense, character reserves an interpretation of being that may be at variance with the person’s subjective notion of their essence. It is a clash between the discourse of character—which speaks through the aesthetic of being—and the voice of desire: the subject’s play of the imaginative possibilities of self.

This is, perhaps, best illustrated in a person who is (as existent-structure) a certain way. He handles himself and others in a certain style. A syntax of being and relating. Now, all this may be unknown by the subject and, indeed, at wild variance with his own “internal world” or, at least, his experience of the world.

It raises the question: What is subjectivity? Or, can there be a genuine subjectivity without hearing from the discourse of character? I think the discourse of character is a mute speech. It means “listening” to one’s silent speech, almost as if we bear with us a shadow self who prints in an aesthetics of being a dialogue with an absent object. In psychoanalysis, this absent object may reappear in the transference.

In fiction, at least the modern novel, character may exist alongside consciousness; in particular, the consciousness of the author … or the world of the novel. What is the discourse of the self? Does the consciousness of the author grapple with the violence of character; or, is it remedied by superficial placing in indexical tongues (sociological matrices) rather than as an idiomatic—unconscious—discourse of the ego: the impersonal self?

What novels do I know of where the subject grapples with character? Moby-Dick, Crime and Punishment. It means a conscious confrontation with the mute determinacy of one’s idiomatic discourse. Character is autistic, in that the receiver of the discourse is absent (the object of all characterological defenses) and the language is, thereby, a dead language. It is the fact that character is a dead language—a language no longer spoken between the original speakers—that gives critics the sense that character is conservative, or inhibiting.

Most novelists understand only the effect of character—that is, linking it with mute determinacy—and this principle is then reprinted in a novel, in social terms (cf. Goffman), but that is not the truth of character, which is deeply enigmatic and aggravating.

Many novels are an attempt to escape the enigma of character by a manic-omnipotent staging of character, giving to themselves a control over character—“characterization”—that is a denial of the very experiences of one’s character.

Recent psychoanalytical studies of the self—in particular, the borderline and narcissistic—are concerned really with a patient whose primary speech is character, whose “subjective” life is blank or chaotic and who refuses to be informed as a subject, of themselves as a character.

Character is destiny if understood, and fate if not understood.

Few authors permit this determinacy to be with them. Their act of omnipotent creation defies destiny. Yet some writers do: Melville, Shakespeare.

December 15, 1977

“Denial and paranoia”

A patient denies memory and both severs and dissolves linking, so he has no internal, accrued sense of self. He has no tradition upon which he can rest. His unconscious motivation is to deny the absence of a transformational object and to reject what is, to use the semiology of the self as a reproach to the other, who must feel guilt.

But, the attack on linking leaves him without structured psychological means of living-in-the-world. To survive, he uses paranoid vigilance—to scan the environment—instead of psychic insight, to know the self. Hence, paranoid thinking is a defense against anxiety surrounding survival of the self, that occurs when there has been an unconscious subversion of psychological insight. That is why he is not concerned with knowing himself or with insight, but only with how I feel about him and whether he is in trouble or not.

Christopher Bollas is a psychoanalyst and writer whose books include The Shadow of the Object, Cracking Up, and Meaning and Melancholia, among others. This extract is adapted from Streams of Consciousness: Notebooks, 1974-1990, which will be published by Karnac Books in England in October.

The city of Linz is all about the future – but that wasn’t always the case

From the November 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here. On 17 September 1979, officials from the Austrian city of Linz, including its mayor, congregated at the local airport. A red carpet had been rolled out in honour of a ‘special guest’ arriving from New Jersey to speak at the launch of Ars Electronica Festival the following day. His name was SPA-12, a robot with an orb-like head…

New York Art Reviews by John Haber

These have been tough times for art criticism. Just this spring and just here in New York, Roberta Smith announced her retirement from The New York Times. Not two years before, in October 2022, Peter Schjeldahl died of lung cancer at age eighty.

The double blow means so much more coming from such prominent and reliable writers at essential publications. Smith has been co-chief critic at The Times since 2011, where she has built a top-level roster, but no one cuts to the quick like her. Schjeldahl began writing for The New Yorker in 1998. Each had come to the right place. How many other newspapers have taken daily or weekly criticism as an imperative, and what other magazine would give a critic a two-page spread as often as he liked? The loss of their most influential voices should have anyone asking what else has changed.

They have left behind a changing critical landscape—one that they could never have foreseen or intended. It values artists more than their art, as seeming friends and real celebrities. It covers the business of art, without challenging art as a business. It cares more about rankings than seeing. It gives all the more reason to look back and to take stock. Good critics, when you can still find them, are looking better and better.

Peter Schjeldahl could see his death coming—clearly enough that he announced it himself, in place of a review, as “The Art of Dying.” It shows his insistence on speaking from his perspective while demanding something more, about art and language, and it lends its name to one last book of his criticism. He had been a poet, fans like to point out, and he must have seen the same imperative in poetry as well, just as for William Wordsworth reaching for first principles on long walks across north England’s Lake District. Schjeldahl quickly took back his finality, perhaps overwhelmed by letters of sympathy and offers to replace him. Death was not so easily dissuaded.

He was a stylist, but not to call attention to himself. He was not one to wallow in the first person at the expense of art. Rather, his point of view helped him engage the reader and to share his insights. One essay described his “struggles” with Paul Cézanne, which must sound like sacrilege in light of the artist’s place in the canon. And then one remembers that Cézanne painted not just landscape, portraits, and still life, but his struggle with painting itself—what Maurice Merleau-Ponty called “Cézanne’s Doubt.” Schjeldahl, too, had his doubts, and they led him to unforeseen conclusions.

He was most at home with someone like Cézanne, at the birth of modern art. Still, his interests ranged from Jan van Eyck, in a memorable article on restoration of The Ghent Altarpiece, to art in the galleries. Roberta Smith, in turn, was mostly content to leave art history to her fellow chief critic, Holland Cotter. I shall always remember her instead as literally climbing over contemporary art, in a photo together with Kim Levin from their days at the Village Voice. It gets me going each year through my own self-guided tours of summer sculpture in New York’s great outdoors. Smith, though, never does get personal, and she is not just out for a good time.

She had a way of landing at the center of things, going back to jobs at Paula Cooper, the first gallery in Soho, and The Times, where she had freelanced before coming on staff in 1991. She promises to keep going to galleries, too, “just to look.” Yet she has a way of expressing her doubts, serious doubts, about what she praises and what she seeks out. All that “on the other hand” can make her a less graceful writer, but it keeps her open-minded and critical.  It is particularly welcome at a publication eager to suppress doubts in favor of hit counts. But I return to trends at The Times and elsewhere in a moment.

It is particularly welcome at a publication eager to suppress doubts in favor of hit counts. But I return to trends at The Times and elsewhere in a moment.

This could be a time not to mourn or to bury writers, but to celebrate. There have been worse in the past, and there will be strong voices in the future. Those old enough to remember Hilton Kramer at The Times will still cringe at his dismissal of postwar American art. His colleague, Grace Glueck, dutifully soldiered on despite obstacles to women. (John Russell brought a welcome change, and I still consult his survey text in The Meanings of Modern Art.) Besides, no critic can make or break a publication.

Smith had already brought on Jason Farago, who revives an old approach to art history going back to John Canady in the 1960s, walking a reader through a painting one detail at a time. It works well with interactive Web pages in the present. Cotter remains as well, at least for now, free to focus on what matters most to him—diversity in artists, especially gays and Latin Americans. With its typical care, The New Yorker took more than a year to come up with a successor to Schjeldahl, and it did well. Jackson Arn teems with insights, enough to have me wondering what is left for me to say, and, like Schjeldahl, he is not above telling one-liners. And yet something else, too, has changed that could defeat them all—and that is so important that I leave it to a separate post next time and to my latest upload.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.

The Paris Review – New Books By Emily Witt, Vigdis Hjorth, and Daisy Atterbury

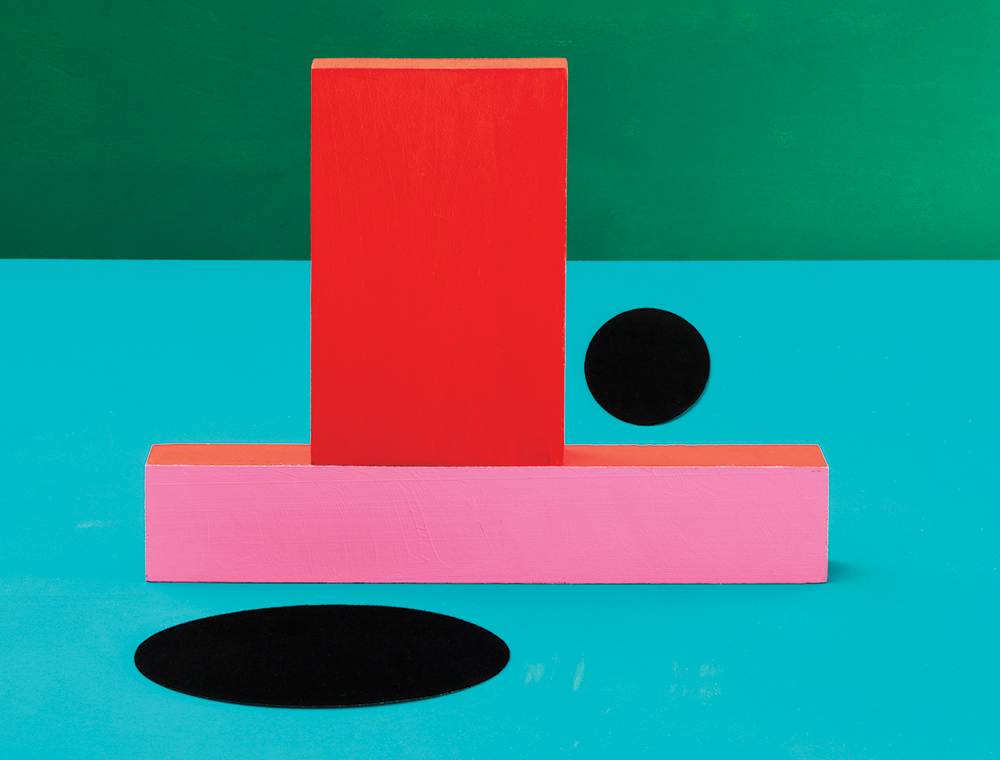

Erin O’Keefe, Circle Circle, 2020, from New and Recent Photographs, a portfolio in issue no. 235 (Winter 2020) of The Paris Review.

I did not have a good time reading Vigdis Hjorth’s novel If Only. I felt, in fact, kind of abject—but something about the novel compelled me forward, in a way that sometimes actually confused me. I found myself reading fifty pages, putting it down, picking it up a week later and once again being unable to stop reading, then abandoning it for another week. It was a discomfiting instance where in returning to the bleak narrative world of the novel I felt almost like I was mirroring the behavior of its main character, Ida, who returns again and again to a love affair that seems to offer her nothing but pain. Why was I reading this book that made me so angry, uncomfortable, irritated? Because it was, maybe, the kind of discomfort that can reconfigure certain aspects of the way you see the world, whose insights or the shadows of them seem to recur long after you’ve closed the book—and so they have, as I thought last night of an image from it, Ida and her lover at a restaurant in Istanbul, gorging on champagne, telling the waiter they were just married even though they weren’t.

If Only—published in Norwegian in 2001, but published in English translation by Charlotte Barslund for the first time this month—is a novel about obsessive love. It is one of a spate of recent novels that take all-consuming desire as a theme: Miranda July’s All Fours and Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos both deal with a passion that veers into misery at times, the kind of passion that is transformative only because it shatters lives. But If Only is by far the bleakest of these; in fact, it is one of the bleakest depictions of a relationship I have ever encountered. The affair obliterates Ida; it cuts her off from the people around her, including her young children; it makes her act erratically and occasionally dangerously. The relationship has many of the same qualities as prolonged substance abuse—and it is no coincidence that Ida and her lover constantly binge on alcohol, too. The novel offers neither redemption nor transcendence as its resolution. And yet Hjorth makes this relationship and its aftermath legible to us as a part of the human experience—one that we can’t extract from the type of love we do consider desirable or healthy. At the end of the book, we might find ourselves wondering, as Ida does: “If only there was a cure, a cure for love.” And we might realize, even as we wish this, that we don’t actually mean it at all.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

I want to recommend the final, fourth volume of Michel Leiris’s autobiographical project, The Rules of the Game: Frail Riffs, recently published by Yale’s Margellos series. Lydia Davis—whose fiction, essays, and translations of Proust and Flaubert amaze me—rendered the first three volumes; volume four is excellently translated by Richard Sieburth. Alice Kaplan has written an incisive essay on Leiris, and Frail Riffs, for the current issue of The New York Review of Books. Alice K. is another international treasure whose books will be known by anyone who reads The Paris Review, I would guess. Especially, but not only, The Collaborator, which summons so much about the political winds of the twenties and thirties blowing through the Parisian literary world, and about the postwar epuration in France, which Céline eluded by fleeing to Denmark, and which Robert Brasillach didn’t. Elude, I mean. (Whether this “fine literary writer” should have been executed for treason or not is, for me, a question one could settle one way at breakfast and the other way at dinner. Sartre or Camus, take your pick.) Anyway: Leiris, who writes the most pellucid and persuasive sentences. Whose abjection I welcome more than anybody’s egotism. His writings a bonanza of formidable insights conveyed with the unrushed elegance of a Saint-Simon. Leiris is incomparable, a Vermeer in a world of Han van Meegerens. Frail Riffs is pure pleasure, in the way Proust is pure pleasure—you can open to any page and just surrender yourself to the music of time that saturates it. The early entry in Frail Riffs, describing the prologues of Goethe’s Faust and their effect upon him as a teenager, is enough to turn any reader into a Leiris devotee.

—Gary Indiana

Emily Witt’s Health and Safety begins in Gowanus in 2016, where the Future Sex author is set to give a lecture called “How I Think About Drugs.” She speaks from a Google slide about Wellbutrin, which she used to take, and the distinction between “sort-of drugs” (pharmaceutical) and “drugs” (illegal). After quitting Wellbutrin, at thirty-one, Witt broke a yearslong illicit-substance fast by smoking DMT at Christmastime. This was the beginning of a drug journey of sorts, one involving ayahuasca retreats in the Catskills with her then boyfriend, a sensory-deprivation-tank attendant, and a large dose of mushrooms taken in a Brooklyn apartment. After her speech she meets Andrew, a Bushwick DJ. He soon introduces her to another context for and type of drug-doing: raving. She falls in love. They soon move in together at Myrtle-Broadway.

“Being in love made me happy,” begins chapter five, “and I lost interest in channeling all of my knowledge about nutrition, disease, and medicine into a life of perpetual risk management.” Witt began to see her former orientation toward health and wellness as narrow and individualistic, whereas raverly values were collectivist, abolitionist, and harm reductionist. To be one of techno’s real appreciators meant thinking through its lineage in Black American Detroit and how it morphed in Berlin clubs; it meant learning about Afrofuturism, Deleuzian metaphysics, and Narcan administration. It could all feel overly theoretical, because the real point of doing ketamine at Nowadays is having fun, but even the most pretentious scene fixtures were interesting in their own ways. Witt is intrigued by techno’s embrace of pessimism as praxis: a deep-house artist named DJ Sprinkles uses part of their set to drive home why they use the term transgendered instead of transgender, then tells their audience they’re all a bunch of normie losers. Sprinkles is compelling because their unapologetic manner gets at realer issues than does the tone-deaf #Resistance-era small talk that was unavoidable at the time in New York.

Witt’s partying coincides with Trump’s election, the beginning of the #MeToo movement, Parkland, Kenosha, the protests in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, January 6. The Trump administration disturbed many Americans’ sense that we shared a definite political reality; our widened Overton window, at least, began to reveal the racial and socioeconomic injustices that white, middle-class liberals had claimed ignorance of. During this period, Witt joined The New Yorker as a staff writer while attending Black Lives Matter protests on the side with Andrew. Health and Safety poses sharp questions about what it means to watch history unfold versus to participate in its making, and about what it means to write about brutality when your friends are in harm’s way. These questions don’t resolve, as if to remind that discourse has little impact on the machinations of capital and state violence.

Witt’s reflections on the loop of reporting assignments—like being sent to watch Lizzo play a Shake Shack–sponsored set at a D.C. March for Our Lives rally—and sleepless nights at Bossa Nova Civic Club that comprised her pre-pandemic life are spectacular. So are her extremely specific notes on tripping: “I just saw some patterns that faintly buzzed in the marker colors of my childhood—the ‘bold’ jewel-toned spectrum that Crayola started selling in the early 1990s.” While reading Health and Safety, I couldn’t stop thinking about how the defamiliarizing effects of psychedelics are not unlike those of a well-constructed sentence, the kind that catches you off guard with its accuracy.

—Signe Swanson

The Kármán line, in astronomy, is the definition of the edge of space: the line at which Earth’s atmosphere ends and outer space begins. It’s a geopolitical rather than physical definition—it’s about fifty miles above sea level, though it is not sharp or well defined, and below the line, space belongs to the country below it, while above it, space is free. Daisy Atterbury’s new collection of poetry, The Kármán Line, to be published by Rescue Press next month, describes the line’s psychological import, characterizing it as a clearly defined yet impossible-to-name boundary between the known and the unknown. From the poem “Sound Bodily Condition”: “I want to learn how to get at the thing I don’t yet know, the blank space in memory, the experiences I should have language for and don’t.” Atterbury’s book is at once a math-inflected lyric essay; a rollicking road trip; a field guide to Spaceport America, the world’s first site for commercial space travel, located near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico; and a collection of intimate poems.