First Folios on the Loose, and Other News

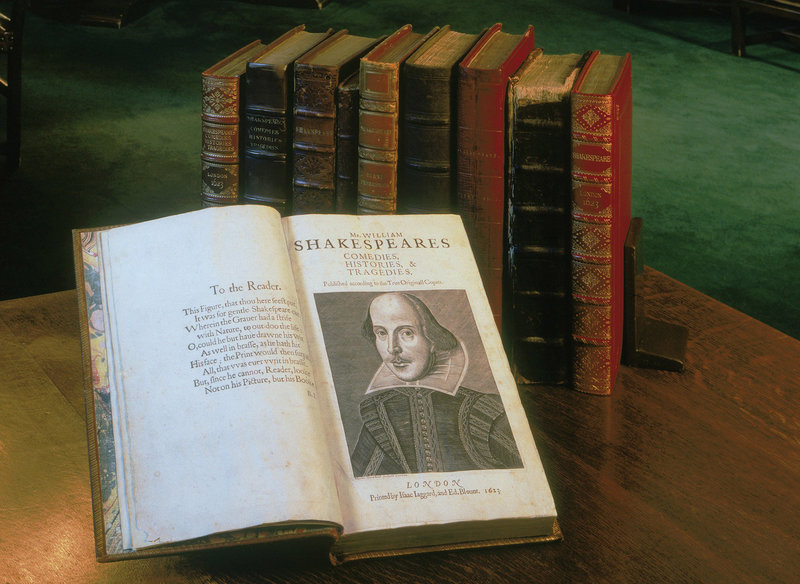

- To celebrate the four-hundredth anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, the Folger Library is sending Shakespeare’s First Folio to all fifty states. Good news for his fans, yes, but maybe for enterprising book thieves, too? “The Folger has eighty-two First Folios—the largest collection in the world. It’s located several stairways down, in a rare manuscript vault. To reach them, you first have to get through a fire door … (if a fire did threaten these priceless objects, it would be extinguished not with water—never water near priceless paper—but with a system that removes oxygen from the room). A massive safe door comes next—so heavy it takes two burly guards to open it, and then yet another door, which triggers a bell to alert librarians that someone has entered. After that, there’s yet another door and an elevator waaaay down to a vault that nearly spans the length of a city block…” No word on how many armed guards and armored trucks will accompany the Folios on their cross-country tour.

- Carlo Gesualdo died about four hundred years ago, too—but contemporary celebrations of his work tend to be overshadowed by a grisly episode from his biography: namely the allegation that he killed his spouse. “The idea of an aristocrat murdering his wife in flagrante has proved irresistible, and only very secondarily do people ask how such behavior may have been turned to creative ends. And when they do listen to the music, they very quickly find exactly what they expect: tortured, dissonant, disjointed (no pun intended) writing which obviously shows a psychopath at work … From the start the marriage was not a success, and soon there were stories of Carlo maltreating his wife. Within three months he was journeying back to Naples without her, and once back in his castle he descended into a kind of madness, which eventually extended to a court case. The records survive and give a flavor of what was under discussion: ‘Menstrual blood is a kind of poison which, if imbibed and not treated immediately, will eventually lead to a person’s death.’”

- Do you have one of the thousand hand-numbered copies of Theodore Roethke’s debut collection, Open House? It came out in 1941, and the Roethke House, in Saginaw, Michigan, is conducting a census to track down all the copies. One of them may be in the clutches of the Auden estate; he gave the book a glowing review: “Many people have the experience of feeling physically soiled and humiliated by life; some quickly put it out of their minds, others gloat narcissistically on its unimportant details; but both to remember and to transform the humiliation into something beautiful, as Mr. Roethke does, is rare. Every one of the lyrics in this book, whether serious or light, shares the same kind of ordered sensibility: Open House is completely successful.”

- When do we become adults, really? At what point can one say with certainty that one has sloughed off the last vestiges of youth? Wordsworth said the child is father of the man, which … doesn’t answer the question at all, actually. But others have tried to, even if the answer will never really come: “Steven Mintz writes that adulthood has been devalued in culture in some ways. ‘Adults, we are repeatedly told, lead anxious lives of quiet desperation,’ he writes. ‘The classic post-World War II novels of adulthood by Saul Bellow, Mary McCarthy, Philip Roth, and John Updike, among others, are tales of shattered dreams, unfulfilled ambitions, broken marriages, workplace alienation, and family estrangement.’ He compares those to nineteenth-century bildungsromans, coming-of-age novels, in which people wanted to become adults. Maybe an ambivalence over whether someone feels like an adult is partially an ambivalence over whether they even want to be an adult.”

- There’s another thing blurring the line between childhood and adulthood: kids and grownups both cuss. As a kid, Mark Edmundson swore with impunity, perhaps even with grace, and he wonders why adults are so often shocked by their foul-mouthed offspring: “When a mom overhears her beloved child swear for the first time, her heart contracts until it feels like it will disappear. But imagine how she feels when she overhears a son or daughter who not only curses, but is truly adept at profanity … What if mom hears her little boy, not long out of Pampers, still in shorts, reel off a euphonious string of curses that sounds like the work of a top sergeant in rage at his recruits? … A shrill cry of ‘shit!’ from your five-year-old suggests that even with all the preparation you had and all the thought and all the love you invested, you didn’t manage to get it right this time.”

SOURCE: The Paris Review – Read entire story here.