No more Mr Nice Guy: how Hugh Grant transformed himself into an edgy national treasure | Movies

This week sees the release of Heretic, Hugh Grant’s 45th feature film. Few critics would have predicted that length of career after his pouting 1982 debut in Privileged, a pretentiously shonky whodunnit featuring several of his fellow Oxford students. For the next decade he wasn’t so much a fringe actor as an actor with a floppy fringe, invariably cast as a posh, slightly foppish Englishman, doomed to be forever brushing his lustrous hair back from his finely chiselled features.

Then 12 years on everything changed with the release of Four Weddings and a Funeral. More accurately, the floppy fringe remained, but now it was employed as comedy cover for a strikingly diffident kind of romantic hero. Overnight Grant was catapulted into the realm of international fame, going on to co-star with his haircut in a series of not wildly dissimilar romcoms.

A horror film, Heretic is a world away from all that. Grant is now 64, the curtain mop is long gone and the boyish charm has matured into something far more dangerously charismatic.

He plays Mr Reed, who is driven by a provocative yet pitiless logic, and betrays more than a touch of evil. It’s not his first bad guy. He’s been flirting with villainy for a while in films like Paddington 2 and Dungeons & Dragons, not to mention his suavely ruthless Jeremy Thorpe in the much-lauded TV drama A Very English Scandal.

Mr Reed, though, occupies much darker territory. Grant said recently that the role is part of “the freak-show era” of his career. The change in direction has suited him, not least because a roguish character, as he’s made a point of saying, is closer to his own.

The stammering toff who seemed to have fallen out of an early Evelyn Waugh novel was his party piece, and it was used to brilliantly subversive effect in Roman Polanski’s Bitter Moon, which predated Four Weddings. But it was perfected for Richard Curtis and it became his go-to public persona.

As he told the New York Times: “I thought if that’s what people love so much, I’ll be that person in real life, too.”

That job grew much more challenging after his arrest in June 1995 following a brief encounter in a BMW on Sunset Boulevard with sex worker Divine Brown. His timid romantic act appeared to have been dealt a fatal blow, but Grant doubled down, dealing with the fallout in character, as it were.

The nervous young man who squirmed in the Tonight Show armchair while Jay Leno asked: “What the hell were you thinking?” managed to perform a delicate piece of image repair. In this endeavour he was ably supported by his then girlfriend, Elizabeth Hurley.

With her photogenic looks and preference for well-ventilated clothing, Hurley had become a fixture in the UK press, making the couple a red-carpet dream team. The attention they drew would later have far-reaching repercussions when Grant discovered what press intrusion really entailed.

The sordid sex crisis deftly negotiated, Grant’s star continued to rise in a trio of Curtis-scripted films: Notting Hill, Bridget Jones’s Diary and Love Actually.

It was in the middle one, in which he played the caddish Daniel Cleaver, that Grant began to grow as a comedic actor, famously ad-libbing some of the film’s best lines. Next year he reprises Cleaver in the fourth Bridget Jones film, Mad About the Boy.

“I think he did feel apprehension about stepping out of that floppy, tongue-tied English character,” recalls Bridget Jones’s Diary director Sharon Maguire. “I remember him being really pleasantly surprised and relieved the first time he saw the movie at the New York premiere … and only a teensy bit jealous that Colin Firth got just as many laughs.”

after newsletter promotion

The making of that film coincided, roughly, with his breakup with Hurley. There followed a prolonged period of intermittent dating and an ever-more fractious relationship with the tabloids. The key text of this period is About A Boy, in which he plays a man in flight from romantic commitment. Grant acknowledged that he put a lot of himself into the role.

Yet suddenly, in his 50s, the confirmed bachelor contrived to father two children who are now 13 and 11 with the actor Tinglan Hong, and in between a son with Swedish TV producer Anna Eberstein, with whom he had two more children and to whom he has been married for six years.

Grant, whose father was an ex-army officer who worked in the carpet business and mother a French teacher, had originally wanted to be a writer. Although he more or less fell into acting, he’d always been a performer. Old schoolmates at Latymer Upper School in Hammersmith, West London, still talk of his mesmerising recital of Eliot’s The Waste Land.

But without formal drama training or a background in the theatre, Grant, even by the neurotic standards of most actors, nurtured a deep streak of professional insecurity – he has complained of being paralysed by panic attacks when filming.

“I got the strong impression,” says Maguire, “that Hugh was filled with loathing at his own acting and yet he was hugely conscientious about the process of acting, a perfectionist who often contributed gold in terms of the comedy and authenticity of a scene.” His exacting approach to work has not always won him friends on set. Robert Downey Jr called him a “jerk” after they made Restoration together in 1995. And Jerry Seinfeld, who directed him in Unfrosted, was only half-joking when, earlier this year, he described Grant as “a pain in the ass to work with”.

For all his self-criticism – he’s said that people were rightly “repelled” by his stumbling Englishman character – Grant also knows his own worth, not just financially but also in terms of industry longevity and position. The man who appears nowadays on talk shows with his well-honed anecdotes and waspish self-deprecation is a supremely confident veteran of the business of selling himself.

There’s also an added steeliness, a disinclination to suffer fools, that has been sharpened in the legal battles waged since he learned that his phone had been hacked by the now defunct News of the World. A leading figure in Hacked Off, the campaign group that seeks reform of press self-regulation, Grant settled a lawsuit with the Sun this year, having accused the paper of hiring a private investigator to break into his flat and bug him.

He said on X that he would have liked to go to court, but if he’d been awarded damages that were less than the settlement offer “I would have to pay the legal costs of both sides”, which he said could be as much as £10m, adding: “I’m afraid I am shying at the fence.”

Taking on Rupert Murdoch is one thing, but Grant is also not averse to showing his tetchier side to those lower down the media ladder. Last year his stilted interview with model Ashley Graham on the Oscars red carpet inspired almost as much condemnatory newsprint as his other Hollywood interaction three decades earlier with the unfortunate Brown.

When asked what he thought of the event, he compared it to Vanity Fair. He meant the Thackery novel, but Graham assumed it was the magazine after-party. The conversation only went downhill from there. Grant was derided as a snob and self-important, though it’s fair to say that some of his fanfare-deflating drollery was lost in cultural translation.

Then again, maybe he wasn’t just bored with banality but instead, with one eye on his career, he was establishing his new edge in the public imagination. With Grant it’s impossible to know. His real motivations and character are buried beneath geological layers of artifice, irony and a highly developed celebrity defence system.

He could probably write a wonderfully scabrous exposé of the film world and himself in the tradition of David Niven and Rupert Everett, but it’s far more likely he’ll concentrate on the job in hand: gradually occupying the position of a national treasure.

Web designers: tiny ‘peacock spiders’ depicted in all their glory – in pictures | Art and design

Australian Maratus spiders, which measure 3-5mm, are known as “peacock spiders” because of the extravagant colourings they display during courtship rituals and combat. Sydney-based artist Maria Fernanda Cardoso became fascinated with the tiny spiders, which she has depicted in the series Spiders of Paradise, in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Together with scientific imager Geoff Thompson and Queensland Museum entomologist Andy Wang, she created composite images of their distinctive patterns using more than 1,000 source photographs for each species. “They’re cute, they’re exclusively Australian,” says Cardoso of the spiders. “They’re incredibly expressive and very flirtatious. The male wants to get all the attention of the female, like birds of paradise.”

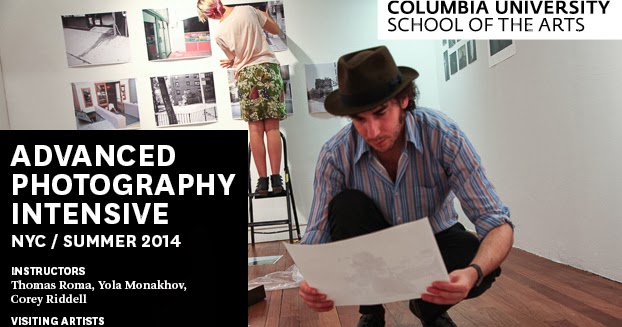

The Advanced Photography Intensive at Columbia University School of the Arts

Our partners at Columbia University School of the Arts have announced its Advanced Photography Intensive, which aims to engages students in all elements of photographic practice and the development of a portfolio. A combination of technical tutorials, individual meetings with internationally renowned artists and art professionals (Thomas Roma, John Pilson, Elinor Carucci, Michael Spano, Susan Kismaric and Vince Aletti), as well as a series of seminars and group critiques, provide students with the tools they need to advance professionally and further develop the core elements of their practice.

The Advanced Photography Intensive creates an exceptional workshop environment where students have 24-hour access to traditional and digital facilities, coupled with daily hands-on assistance from experienced faculty and staff, culminating in a group exhibition at the LeRoy Neiman Gallery. Students are expected to produce work independently throughout the six-week term and fully dedicate their time and efforts to the course.

The course is designed for several distinct types of students: exceptional undergraduates passionate about photography, college graduates preparing to apply for MFA programmes, experienced photographers looking to gain knowledge of the photographic tradition and its advanced techniques, and seasoned artists and teachers wishing to rigorously develop their practice through a critical dialogue with faculty and other students.

For more information on the features of the course, and how to gain admission click here.

Source link

Review: BEDROOM FARCE at Players Circle Theater – BroadwayWorld

Review: BEDROOM FARCE at Players Circle Theater BroadwayWorld

Source link

The week in classical: Wexford Festival Opera: Le convenienze ed inconvenienze teatrali; The Critic and more | Opera

Two hundred years before that hilarious farce The Play That Goes Wrong became a West End hit, Italian playwrights had come up with a similar comic formula, targeting the often disastrous nature of rehearsals before a show. Later, Gaetano Donizetti grabbed the idea and took it into the realm of opera, walking us backstage to witness the tantrums, jealousies, fist-fights and sheer panic that sets in when the clock is ticking inexorably towards curtain-up.

His two-act comedy Le convenienze ed inconvenienze teatrali this year joins a laudably long list of rarely heard works revived by Ireland’s Wexford Festival Opera since 1951. It’s a piece that fits perfectly into this season’s theme of “theatre within theatre”. Orpha Phelan’s brilliantly inventive new production, graced with a golden cast, has the whole house rocking with laughter from start to finish.

Canadian coloratura soprano Sharleen Joynt combines superb technique with great comic timing as the impossible prima donna Daria, who refuses to rehearse with a mere secondo soprano Luigia (Paola Leoci) – a decision that hastens the arrival of every director’s nightmare: Luigia’s domineering mother, Agata, played by the outrageous bass-baritone Paolo Bordogna. Agata steamrollers her way into the opera, shamelessly promoting her daughter, demanding cuts and rewrites and ignoring all objections. She can’t read music, sings badly, dances hilariously (even on pointe) and scatters cheerful catastrophe wherever she goes. It’s a wonderful performance.

Wexford’s new edition of this firecracker updates the 19th-century tradition of including in it music not written by the composer; the tenor Guglielmo (Alberto Robert) turns up thinking he’s rehearsing The Sound of Music. Later we get a very classy burst of Leonard Bernstein’s Candide. Amy Share-Kissiov devises some terrific dancing, and Danila Grassi conducts the festival orchestra with passion and precision. At the curtain call she wept as the opening night’s rapturous applause rang out; surely not the only tears of joy shed that night.

Compare Italian Giacomo Puccini and Anglo-Irishman Charles Villiers Stanford and they would seem to have nothing more in common than the year in which they died – 1924 – and yet both composers burned with a passion for opera. Puccini enjoyed wild success, amassing a fortune equivalent to $200m in today’s money, while Stanford found rejection, his works for the stage sinking almost without trace. You can hardly move for Puccini centenary revivals this year, but Stanford’s nine operas have had precious little attention. Justifiably so, some might say.

Wexford disagrees, and is honouring the Dublin-born composer by reviving The Critic, Stanford’s 1916 reworking of Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s 1779 satirical play of the same name. Stanford’s biographer Jeremy Dibble has produced a new performing edition of this surprising curiosity, which fits neatly into the festival’s theatrical theme. What immediately becomes apparent is Stanford’s evident impish sense of fun. He believed wholeheartedly in opera but plainly was not above mercilessly lampooning its pretensions, plots and stars.

Sneer, the critic, has been invited to witness a rehearsal of Mr Puff’s absurd new play The Spanish Armada, which composer Mr Dangle has transformed into an opera. These speaking characters comment on the action while singers portraying figures from the reign of Elizabeth I strut around the stage making ludicrously pointless gestures and getting in each other’s way. Sneer (Arthur Riordan) is quick to spot a flaw in the creaking plot: Walter Raleigh (Ben McAteer) and his comrades have already captured Don Ferolo Wiskerandos (Dane Suarez), son of the Spanish admiral, even though the fleet is nowhere in sight. Puff (Mark Lambert) brushes this aside: he needs to create a love story between the hapless Spaniard and Tilburina, the improbably named daughter of the governor of Tilbury fort.

Stanford reserves his best vocal writing for Tilburina, which soprano Ava Dodd exploits to the full, while the choruses swell with typical Stanford grandeur. Musical gags come thick and fast. Quotations from Wagner, Elgar, Beethoven and Parry pepper the score, and the increasingly desperate plot includes a lost-orphan-found moment parodying both Mozart and Sullivan. There’s even a portentous, doom-laden orchestral introduction to a character who neither sings nor speaks.

Conductor Ciarán McAuley has a lot of fun with those name-that-tune moments, while also caressing Stanford’s often luminously lyrical orchestral writing. John Comiskey has designed a handsome theatrical set, and director Conor Hanratty follows to the letter Stanford’s imprecation that the piece be played in all seriousness. “Any attempt to treat it farcically only spoils the humour.”

The season opened with Pietro Mascagni’s Le maschere, his 1901 bid to escape the shadow of his hugely popular Cavalleria Rusticana by honouring two Italian institutions: commedia dell’arte and the operas of Gioachino Rossini. It doesn’t really succeed in either aim, but director Stefano Ricci and choreographer Stellario Di Blasi give it their best shot, moving the action to a very 21st-century wellness centre. The plot is stock Rossini: father wants to marry daughter to unsuitable man; she has other ideas. It takes far too long to tell a simple tale, but some of the singing is excellent, particularly from sopranos Lavinia Bini as daughter Rosaura, and Ioana Constantin Pipelea as Colombina. Francesco Cilluffo conducts with Rossinian brio.

The three main operas are accompanied by some 70 small-scale recitals, lectures and new pieces over the 16 days of this most friendly of festivals. Chief among them is a contribution from celebrated Irish writer Colm Tóibín, who, with composer Alberto Caruso, has devised a witty, biting, one-act opera about Dublin’s Abbey theatre’s 1911 tour to the US with JM Synge’s controversial work The Playboy of the Western World. Lady Gregory in America is a beautifully fluent, lyrical hour, cleverly staged by Aoife Spillane-Hinks. A young cast is led by mezzo Erin Fflur as the redoubtable Augusta Gregory, making her defiant stand for art against US puritanism, alongside a standout performance from soprano Jane Burnell as the spirited actor Molly Allgood. Today’s America needs to see it.

Star ratings (out of five)

Le convenienze ed inconvenienze teatrali ★★★★★

The Critic ★★★★

Le maschere ★★★

Lady Gregory in America ★★★★

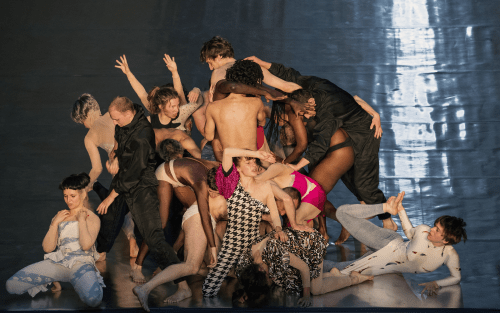

Why art’s obsession with dance endures

Choreographic details are not the only things that can get lost in the theater: contemporary/modern dance history can dissolve into obscurity due to its innate ephemerality and the industry’s preference for creating new live work over preserving the old. As such, the fact that art museums – houses of preservation by nature – have an increasing interest in dance is a great help in the quest to capture, document, and share lesser-known performance histories. The current Edges of Ailey exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, which celebrates the legacy of pre-eminent African-American dancer, choreographer, and civil-rights activist Alvin Ailey, is a prime example. It’s an ‘important political move’ according to Lewis, since postmodern dance figures, such as the Judson Dance Theater collective, who enjoyed a retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) back in 2018, have been the artworld’s key reference point for dance for too long. ‘Historically, Black dancers have been written out of that trajectory, so it’s super important to have someone as iconic and influential as Ailey [celebrated in an art context],’ she says. ‘Finally we can break with a really reductive idea of what dance is.’

While not as easy as acquiring inanimate art objects, museums have become more skilled at collecting and conserving dance over the years. ‘A flat documentation of a great dance piece doesn’t cut it,’ says Wood. Instead, methods such as showcasing products of collaboration between dancers and artists from other disciplines or certifying dancers to serve as living archives of specific works are becoming more common. Carmela Hermann Dietrich and Sarah Swenson, for example, are instructors of Italian-American choreographer Simone Forti’s seminal Dance Constructions (1960–1), which were acquired by MoMA in 2015. Likewise, Wookey is a teacher of Rainer’s Trio A, and was responsible for staging the aforementioned performance of the work in Berlin. Alongside colleagues, she’s currently investigating how the unique verbal lexica choreographers use may be helpful in the conservation process. ‘There’s this old idea that dancers use their body but not their voice, but [they] are incredibly articulate. I have hundreds of note cards capturing [Rainer’s] language,’ she says, explaining that the words she used to talk about dance would be wildly different to someone like Martha Graham. ‘Words [in choreography] are fascinating and open up worlds.’

Richard Parr on His Favorite Bag, Inspiring Art + More

It was clear that Richard Parr was destined to be an architect, putting his visions to paper early on. In elementary school, the left side of his English lesson book was filled with his stories – and a low mark for his less than stellar spelling. On the right side, however, were meticulous drawings of structures, just one example of his love of the built environment. “I drew buildings everywhere, and made them out of LEGO and clay,” Parr says. “I always enjoyed playing with and making spaces.”

His self-education included visits to places in Italy and England steeped in history. When Parr stepped into Basil Spence’s Coventry Cathedral, it was a seminal moment, and he still has the guidebook from that day. Completed in 1962, the new cathedral was built to replace the 14th-century St. Michael’s Cathedral, destroyed in an air raid during World War II. Spence took elements of the past to reinvent the future. For Parr, it represents what he constantly strives to achieve.

Richard Parr Photo: Mark Cocksedge

The architect founded Richard Parr Associates three decades ago, with an emphasis on timeless spaces, created by merging craft traditions and technology. He also appreciates hospitality, and can often be found cooking and entertaining. In the London studio, dubbed the People’s Space, there’s even a bar and a main kitchen. The staff regularly share meals and conversation because they consider breaking bread the ultimate act of giving.

Parr divides his time between two locations where his life and studios are. While he’s energized when working in the city, he disconnects as soon as he arrives at his farm in the Cotswolds. He takes every opportunity to enjoy nature and tend to his kitchen garden.

Parr regrets that he missed out on both A-level art and a foundation year, and he would like to explore different mediums, particularly painting. He’s content though, and like all exceptional leaders, he knows which role each person will thrive in, himself included. “I like to think that I have tapped into most of my usable talents, and seasoned enough to recognize where I am not going to flourish,” Parr notes. “Even within the practice, I am happy to delegate where others can do better than me.”

Today, Richard Parr joins us for Friday Five!

República Dominicana, Facultad de Ingeniería y Arquitectura (FIA), 2022, oil, beeswax, and powdered gold pigment on canvas

Rogelio Báez Vega, whose work I encountered in NADA in Miami in 2022. The pieces are depictions of modernist buildings. The modernist movement is an area of fascination and interest to me. The impact of the ‘International Style’ and its application across the world is a theme that I engaged with when discovering Rogelio’s work. I enjoy seeing the artist exploring the relationship this architecture has in different geographies and politics and I have several works in my collection from diverse areas of the world, exploring the societal dialogue with a built environment that has become universal. As with anything the universality becomes local and it’s the conversation in specific context that interests me.

Many years ago, I encountered the designer Massimo Alba from Milan. His annual collections are a treat and his approach to fashion… the fabrics, colors, texture and cut marries with my own love of comfortable and understated ‘sprezzatura.’ His mandarin collared jackets, which are as European as anything else have become the core of my wardrobe. They are more than they seem, with (like everything he designs) an understated quirkiness that combines the relaxed style of Italian tailoring with interesting and clever fabrics. I wear his linens in summer and his tweeds in winter, velvets, and cord as well. Every year I visit his Brera showroom and make an annual addition.

Photo: Courtesy of The Modern House

Pep and Cuca’s gallery embodies and combines everything I love. Firstly, the very existence of this gallery in Tetbury is a joy and 10 minutes’ drive from home. The combination of contemporary art, 20th century furniture, some extraordinary antiques from both Spain and the British Arts and Crafts movement means I could happily own most of what they have in the gallery! I spent many years living in Spain and the fusion of contemporary architecture with history is something I learnt there and why their choices resonate and works so well for me. Among a number of pieces I have acquired from them are works by Chillida, the Mallorcan artist Guillem Nadal, and a number of pieces of furniture. I bought an Eames coffee table from the 1940s, which is one of the most enjoyable pieces I own and used daily.

My Porter-Yoshida bag goes with me everywhere. It’s the perfect design and could have been tailored for me. I never lose anything into it yet I throw my life into it! It holds everything from my laptop to crayons and is a smart but relaxed non statement piece.

I have chosen something garden related. Gardening or my garden is my escape and where hours of time are expended. My kitchen garden at home fills what was once a concrete yard between my house and my studio. I can find something to eat in it on every day of the year. Spring time seed buying is a ritual and I discovered Vital seeds a few years ago. They sell organic seed and I have a great success rate with everything that I have bought from them.

Works by Richard Parr:

Photo: Gilbert McCarragher

Jodorowsky’s Santa Sangre: Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way

For the writer of these lines there is hardly anything more nightmare-inducing than a circus. With horrific clowns, knife-throwers, dwarves dressed in humiliating costumes and sad-eyed caged animals, the circus somehow manages to encapsulate and represent everything that is wrong and amoral about spectacle, mass entertainment and hierarchical collectives. It comes as no real surprise, then, that Alejandro Jodorowsky picked up such carnivalesque context to stage the traumatic childhood events that unfold into the full adult horror that is Santa Sangre (Holy Blood). This work, which marked Jodorowsky’s return to film making after a 9 year hiatus triggered by the fiasco of the Dune project (which, as we all know, ended up in David Lynch’s hands) and the commercial failure of Tusk, is, however, a story of redemption. The surprisingly optimistic message that emerges amidst this clammy landscape of gruesome murder, orphanhood and paranoia is that, no matter how low one falls, there is always the possibility of starting anew through love, regret and self-awareness. Even the name of the protagonist, Fenix (Phoenix), points to the act of rebirth, the celebration of a new self born from the ashes of a damaged, exhausted carcass.

Jodorowsky is not only celebrated for the bizarrely sublime visual universe he brought to life in films like The Holy Mountain, Fando y Lis or El Topo. He is also well-known as a comic and book author, as a committed tarot reader and also for his development of an alternative therapy he called “psychomagic”, which blends devices from psychoanalysis with esoteric and mystic beliefs and a penchant for implementation through actions (known as “psychomagic acts”) that, seen in another light, could very well be considered performance art. Santa Sangre, filmed in 1989 when Jodorowsky had just turned 60, became the perfect vehicle to explore his particular mélange of interests, turning eventually into a very personal exploration of his relationship with his family, as he himself has acknowledged in several interviews.

Despite having become a slightly facile tool in film studies, a psychoanalytic approach seems unavoidable here. To begin with, the character of Fenix, both as a child and as an adult, are played by Jodorowsky’s sons Adan and Axel (aka Cristobal). Their uncanny likeness reinforces the continuity and credibility of the character as he navigates the narrative’s timeline. Moreover, both actors strongly resemble their father, so every frame oozes a disturbing autobiographical aura. Jodorowsky’s parents never ran a circus in Mexico City, to be sure, only a small shop in Santiago de Chile, but the stifling and overprotective behaviour displayed by Fenix’s parents in the film somehow brings to mind what Jodorowsky reveals of his own progenitors in his autobiography The Dance of Reality, which was first published in 2001. Reading the chapters where he examines his childhood (a period he dramatically entitled “The dark years”) the reader infers that Jodorowsky grew up feeling incredibly frustrated by his parents’ mediocre existence and their desires for him to follow their path, choosing instead to hide in a world of fantasy he eventually materialised through the creative work he came to be known for. Throughout Santa Sangre, Fenix also struggles to rebel against what his parents want of him. As a child, he becomes the collateral damage of his philandering and murderous father’s actions. As an adult, the ghost of his assassinated mother, who visits him in the form of a terrible psychosis, orders him to slaughter every female who flaunts her sexual organs and appetites, and thus embodying the Tattooed Woman, that member of the circus who stole Fenix’s father from her mother and got her killed. Santa Sangre is the story of Fenix’s bitter battle with these demons which, by the end of the film, he miraculously manages to overcome.

Oedipal symbols succeed one another in a constant stream. In one particularly powerful scene, the young Fenix performs his daily illusionist act, transforming his sweetheart, the tightrope walker mute girl, into his own mother. It doesn’t really get more Freudian than that, does it? Also, the Tattooed Woman, Fenix’s foe, is the surrogate mother of the mute girl, Fenix’s good fairy, in case you were wondering. The overbearing mother figure has indeed had a stellar trajectory in the history of horror films. There is nothing like a castrating woman to launch a successful serial killer career. Examples range from Norma Bates in Psycho to Carrie’s mother, Margareth White, with a special mention to Pamela Vorhees of Friday the 13th, who inverts the Oedipal paradigm by becoming a killer mummy herself in order to avenge her son’s brutal death. Along with the sexy, nightgown-clad damsel in distress, the smothering mother is perhaps the most resilient and ingrained psychological fixation that sustains the (horror) genre’s alignment with “patriarchal” female/male archetypes.

As with much of Jodorowsky’s production, Santa Sangre defies classification. It is indeed a horror film, full of spurting blood and gory murder (not in vain was it produced and co-written by Claudio Argento, producer of most films directed by his older brother Dario and of various jewels of the genre such as Dawn of the dead). But Santa Sangre is also a social satire that wittily problematises the manipulation intrinsic to religions and cults, psychiatric wards and other social collectives (who else but Jodorowsky would dare to shoot a scene involving two gay youngsters with down syndrome kissing and being forced to snort cocaine on a trip outside the asylum gone horribly wrong?). Santa Sangre is also a dramatization of real events, namely the gruesome murders and posterior rehabilitation of the first known Mexican multiple killer: Goyo Cárdenas. Finally, with its lush and oneiric use of the streets and architecture of Mexico City, as well as the colours, sounds and gestures typical of the country, this film can be also be seen as a moving image version of its famous ex-voto paintings: tableaux vivants depicting prosaic miracles attributed to the Virgin Mary and other saints. The Mexicans have always had a fondness for finding the miraculous in the everyday, just like Jodorowsky. But while some call it religion, others prefer to call it (psycho)magic.

–

This text was commissioned in 2013 by the artist Darren Banks for his project The Annotated Palace Collection, a weekly blog post inviting writers to respond to one of the fifteen horror films that make up the Palace Collection.

ART TREKS: De Young Museum—Tamara de Lempicka

About the exhibition

Where: Legion of Honor (100 34th Ave., San Francisco, CA 94121)

When: Now through Feb. 9, 2025

Hours: 9:30 am-5:15 pm, Tuesday through Sunday; Closed on Mondays

Tickets: $20 for adults, $17 for seniors (65+), $11 for students (w/ valid ID), Free for youth (17 and under) and Legion of Honor members

Tamara de Lempicka is the first scholarly museum retrospective of the artist’s work in the U.S., exploring Lempicka’s artistic influences and revealing the process behind works that have become synonymous with Art Deco.

After its presentation at the de Young, the exhibition will travel to Houston and be on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, March 9 through May 26, 2025.

PRO TIP: Skip the line and book your tickets online https://www.famsf.org/visit/de-young-tickets-hours

Pejac is DOWNSIDE UP

Pejac is an artist best known for his elusive creation of socially and environmentally-charged work, such as his recent series in a Palestinian and Syrian refugee camp in Jordan.

He will open his first ever major exhibition at the London Newcastle Project Space from July 22-31st; in the lead up to this, he has created an installation, DOWNSIDE UP, on three locations in Shoreditch, London (Redchurch Street, Shacklewell Street and Granby Street).

Check it out.

Cheers.

Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

A migrant agricultural worker in Marysville migrant camp, trying to work out his year’s earnings. Taken in California in 1935 by Dorothea Lange.

In the 1930’s The Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information (FSA-OWI) hired photographers to travel across America to document the poverty generated by the Great Depression, hoping to build support for New Deal programs being championed by President Roosevelt. Marvellous photographers like Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Arthur Rothstein were among the photographers who took part. In all 170,000 photographs were taken and lodged with The Library of Congress. A link to these LC webpages for FSA is to be found in Cardiff Met Electronic Library>Databases A-Z>Farm Security Administration (Cardiff Met password required).

Now Yale University has launched Photogrammar, a platform for organizing, searching, and viewing these historic photographs.

The Photogrammar platform gives you the ability to search through the images by photographer and alsoprovides an interactive map twith geographical information about 90,000 photographs in the collection.

A Painting Today: “All the Fashion”

6 x 8″

oil on panel

sold

The artist Jacques (James) Tissot had an eye for beauty and fashion, the son of parents in the fashion and designer hats business. At a young age, he’d paint clothing in fine detail, a style surely influenced by what surrounded him. He also knew at a very young age he wanted to pursue a career in art.

Allow me to tell you about the woman in Tissot’s painting Mavourneen (Portrait of Kathleen Newton) – raised in England and Agra, India – her father rose from an Irish army officer to chief accountant for the East India Company, and worth mentioning, a strict Catholic. When she was 16, her father arranged for her to marry a surgeon in the Indian Civil Service – she embarks on a trip to her wedding on a ship, where the Captain became obsessed with her and gets his way once they arrived. She married the surgeon, hadn’t consummated the marriage yet – felt guilty – went to a Catholic priest for advice – he told her to fess up to her new husband – he was enraged – filed for divorce – ship Captain said he’d pay for her trip back to England but if, and only if, she was to be his mistress. She gets pregnant, refused to marry the Captain and ran off to live with her sister.

That’s where James Tissot comes in. They meet, he falls madly in love with her – she gives birth to another child said to be his – they live together in domestic bliss for a few years until she contracted tuberculosis. Tissot suffered through her illness, she couldn’t bear it all and overdosed on laudanum and died. Tissot was so distraught, he laid next to her coffin for four days. A true Greek tragedy.