Review: Dallas Theater Center’s ‘Dracula’ comedy is pleasurably silly – The Dallas Morning News

Review: Dallas Theater Center’s ‘Dracula’ comedy is pleasurably silly The Dallas Morning News

Source link

Grace Williams: Orchestral Works album review – vivid playing and striking drama | Classical music

Born in Barry, south Wales, in 1906, Grace Williams was part of the same generation of British composers as Imogen Holst, Elizabeth Maconchy and Elisabeth Lutyens. She studied at the Royal College of Music in London with Vaughan Williams and later in Vienna with the Schoenberg pupil Egon Wellesz, and, as this vividly played collection of orchestral pieces from John Andrews and the BBC Philharmonic illustrates very well, those very different influences continued to coexist in Williams’ music. The disc includes what has become the most frequently performed of her works, the Sea Sketches for strings, five miniatures completed in 1944 in which the string writing recalls early Tippett and Britten. Castell Caernarfon is a prelude and processional composed for the investiture of the Prince of Wales in 1969, but it’s the strikingly dramatic four Ballads, from 1968, and especially the 1939 Four Illustrations for the Legend of Rhiannon, based on an episode from the Mabinogion, and in which Sibelius seems to be added to her personal stylistic mix, that show Williams at her most distinctive.

Allow content provided by a third party?

This article includes content hosted on embed.music.apple.com. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as the provider may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click ‘Allow and continue’.

Listen on Apple Music (above) or Spotify

Philadelphia Ballet At 60, As Ángel Corella Completes Ten Years As Artistic Director

“‘They really flew,’ he said of the years. ‘I could think like a few days ago it was when I arrived, and a lot has changed since then. But I think that this year sort of represents the past, the present, and the future of who we are and where the company is heading.’” – The Philadelphia Inquirer (MSN)

The JF Apartment Merges Brutalism and Minimalism in São Paulo

The JF apartment in São Paulo, Brazil, reimagined by Zalc Arquitetura, represents an inspired blend of brutalist architecture and minimalist design, creating a home that is as much a gallery of art and ideas as it is a living space. Located in the Higienópolis neighborhood, known for its modernist architectural landmarks and cultural vibrancy, the 1,959-square-foot apartment transformation is more than just a renovation – it’s a statement of aesthetic and functional innovation tailored to meet the unique needs of the homeowners, an art-collecting couple with a passion for design.

The concept behind the JF apartment was to craft a space that merges the raw, monolithic nature of brutalism with the clean, uncluttered lines of minimalism. Brutalism, with its emphasis on unadorned concrete and stark geometric forms, is often considered austere, even imposing. However, in the hands of Zalc Arquitetura, the brutalist elements serve as the foundation of the apartment’s identity, while minimalist details elevate the atmosphere, making the space feel open, airy, and welcoming.

The marriage of architectural styles creates a sense of balance, where the rawness of exposed concrete slabs and beams is offset by the deliberate simplicity of the design. By stripping the apartment of unnecessary ornamentation, the architecture itself becomes the art, allowing the natural textures of the materials and furnishings to take center stage. Every element, from the materials to the layout, contributes to an environment that feels both powerful and serene.

One of the most significant changes in the redesign was the apartment’s reconfiguration, which reflects the studio’s commitment to creating a space that is both beautiful and functional. Originally, the apartment had a small service bedroom adjacent to the kitchen – a common feature in older Brazilian apartments. By removing this room, the architects were able to expand both the kitchen and laundry areas, making them more practical for modern living.

The layout now features an open plan that connects the social areas – such as the living room, dining space, and kitchen – while maintaining the privacy of the bedrooms and the suite. This sense of fluidity is enhanced by sliding steel doors that can be closed to delineate the different zones when needed, allowing the homeowners flexibility without sacrificing the overall sense of openness. The integrated design promotes interaction between spaces, making the apartment ideal for hosting gatherings and displaying the couple’s extensive art collection. At the same time, the private areas of the apartment remain secluded, offering a retreat from the more public zones of the home.

One of the standout features of the renovation is the restoration of the original marquetry wood floor. In its previous state, the intricate wooden flooring was hidden beneath layers of epoxy paint, a remnant of the apartment’s earlier design. Zalc Arquitetura saw the potential in this historical element and made it a priority to bring it back to life. The painstaking process of stripping the floor and restoring it to its original condition was not just a design choice but an environmental one. By preserving and revitalizing existing materials, the architects demonstrated a commitment to sustainability, reducing waste while honoring the apartment’s architectural history. The reconditioned flooring now serves as a warm, organic counterpoint to the otherwise industrial and minimalist surroundings, grounding the apartment in its historical roots.

The visual language of the JF apartment is defined by its use of a neutral, largely monochromatic color palette, which allows the natural textures of the materials to speak for themselves. Concrete is a dominant feature, forming the backbone of the apartment’s aesthetic. Exposed concrete slabs and beams lend the space an industrial quality, creating a striking visual contrast with the smooth, clean lines of the minimalist furnishings.

Another highlight of the new design is the incorporation of a curved steel and glass wall, which separates the bedrooms from the social areas. This gentle curve contrasts beautifully with the sharp, linear forms typical of brutalist architecture, softening the space and introducing a dynamic interplay between geometry and fluidity. The curved wall not only adds a sculptural element to the apartment but also redefines the spatial experience. It introduces a sense of movement, guiding the eye and creating a flow that counterbalances the otherwise rigid forms.

The apartment’s subdued color scheme is punctuated by bold accent colors found in carefully selected pieces of furniture, art, and decor. These vibrant elements inject energy into the space, offering moments of surprise and contrast without overwhelming the overall minimalist tone. The thoughtful curation of artwork adds further depth to the design, as each piece is chosen not only for its aesthetic value but also for how it interacts with the space.

To see more projects from Zalc Arquitetura, visit zalc.arq.br.

Photography by André Mortatti.

The Paris Review – Making of a Poem: Sara Gilmore on “Safe camp”

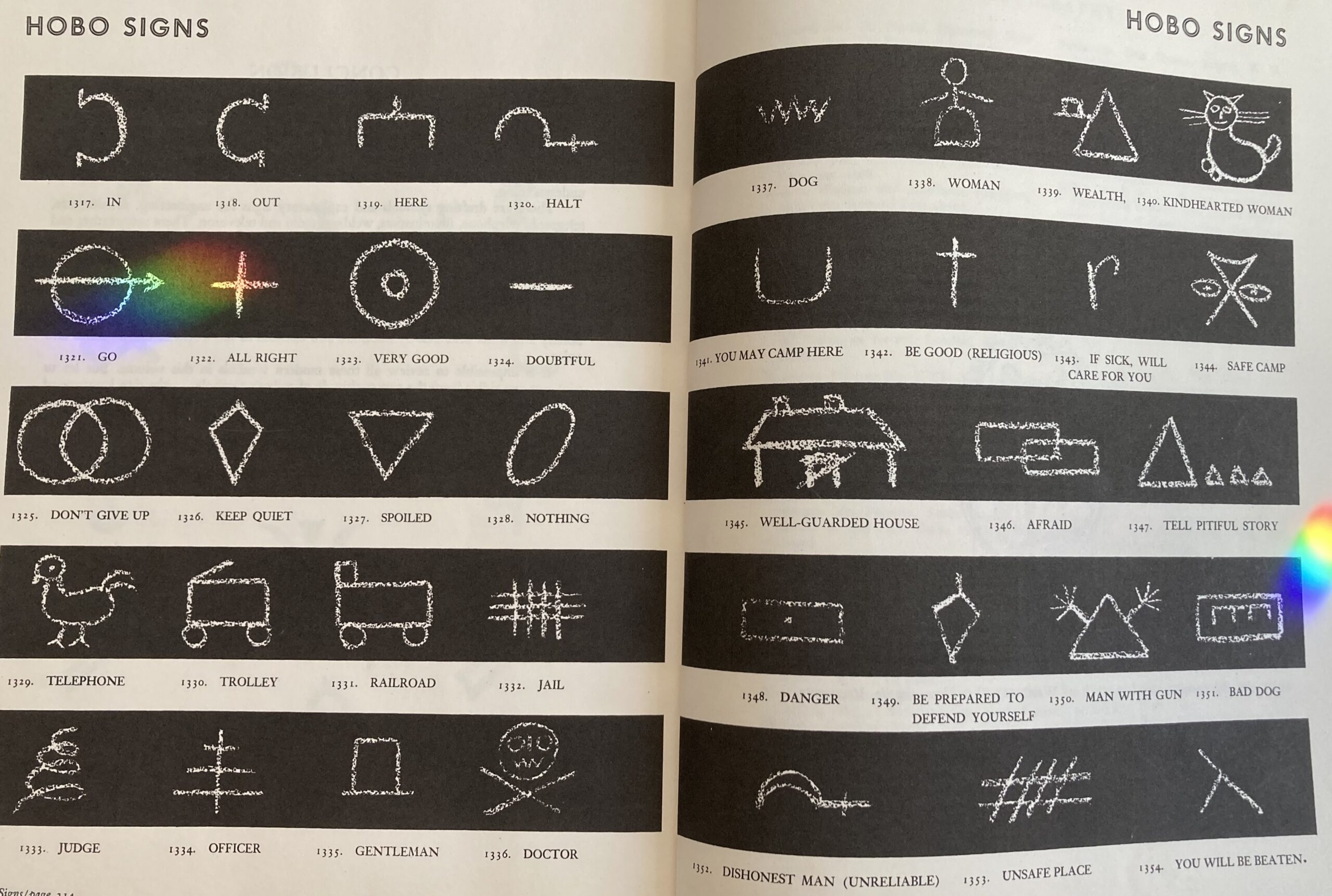

From Ernst Lehner’s Symbols, Signs and Signets.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Sara Gilmore’s poems “Mad as only an angel can be” and “Knowing constraint” appear in the new Fall issue of the Review, no. 249. The poem she discusses here, “Safe camp,” is published on the Daily.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

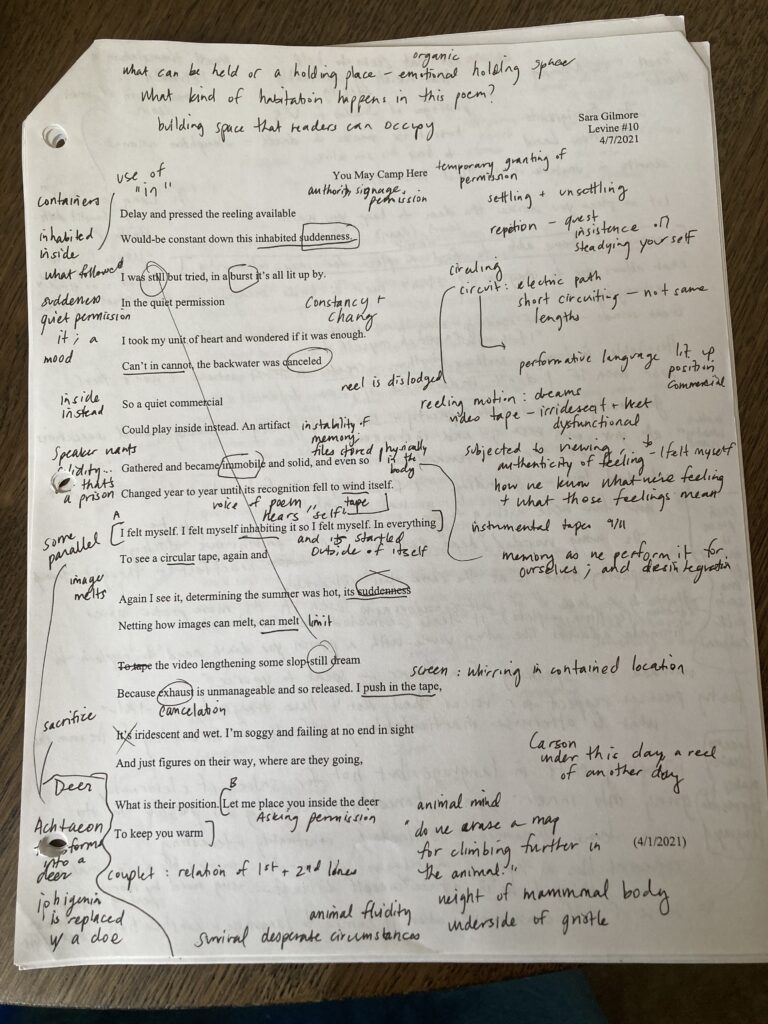

Originally this poem began with the lines “Delay and pressed the reeling available / Would-be constant down this inhabited suddenness.” It never troubled me that the words together didn’t make sense or that I didn’t yet know what they were pointing to—I thought of them as an assembly of beautiful raw material to work with.

As I continued to work on the poem, the image that rose to mind was a ditch along a narrow country road I often strolled down with my son near Mairena del Aljarafe when we lived in Spain. It was filled with trash and reels of unwound VHS tapes. We walked by it hundreds of times. The poem began to grow around the word “reeling”—the “real” along with everything the real is not, the dizzying motion of “reeling,” Anne Carson’s notion “under this day the reel of another day.” This figure of reeling gave into the poem’s circuitry as a whole—the way it shorts out as if its webbing could open to reveal layers underneath, suggesting a kind of sinkhole that either delivers us from or constricts us into a frame of reality that runs along our lives eternally. For me, these sinkholes are dangerous and fascinating.

This is one of the poem’s anxieties—the possibility of a circularity of circumstance or time in which what I’m living today could be the actual present, or a day I lived long ago, or a day I haven’t lived yet at all.

The poem surfaced into clarity in the lines that, in the version published here, appear first. “I was still but tried, in a burst it’s all lit up by.” I like to think the original lines are still there—what my friend Timmy calls the rungs of the ladder that we’re no longer standing on but got us here.

What were you listening to, reading, or watching while you were writing?

The day I started writing, I read Wallace Stevens’s “A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts” for the first time, my son’s stepbrother was born an ocean away, and I went on a walk with my son in Hickory Hill Park in Iowa City. It was April Fools’ Day, a year into the pandemic. My son made a set of cardboard claws to wear. That’s the day the poem emerged, but of course many other days and markers are also embedded into it. I date all the poems I write, maybe to have some anchor in what feels like a sway. I take pictures with my phone of the passages I read, the places I go, people I’m with. With all this underneath, the finished poem can seem like a little white flag waving surrender over a frighteningly infinite and invisible mountain—how do you get at that? I don’t know. I keep trying. What I like about “A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts” is the strength it finds in intimacy. It’s not afraid to say things like “In which everything is meant for you / and nothing need be explained.” In “Safe camp,” I think I got a little closer to conveying strong emotion and feeling outside explanation—strong love, strong belonging, without a tether to fixed place or meaning, the resistance to have those things outside any formal permission.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write? Are there hard and easy poems?

Writing a poem is the easiest and hardest thing in the world to do. Easy in the sense that it’s a human impulse, like singing in the shower, and difficult as far as the huge emotional and intellectual toll it takes. I wrote “Safe camp” quickly, first in my head and then on my phone. I repeated its lines over and over to myself. Two days later I had my second COVID vaccination in Washington, Iowa. When I drove back home, I had a sense of calm, and I knew the poem was good.

How did you come up with the title for this poem? Were there other titles you thought about? Why didn’t you go with them?

“Safe camp” belongs to a cycle of serial poems written around the symbols that itinerant communities have historically used in the U.S. After the Great Depression, as people (many of whom were teenagers) moved across the country looking for work, they would leave scratch marks or markings in chalk outside the places they visited, to tell others what those places were like. For many years I’ve had a copy of Ernst Lehner’s Symbols, Signs and Signets, which includes a catalogue of these visual symbols and verbal descriptions of their meanings: “Owner is in,” “Keep quiet, “Bad dog,” “Safe camp.” There’s something flat and solid about these descriptions that contrasts with the way I write.

So, I would write as I do but title the poems in the order the symbols appear in Lehner’s book. And I knew where I was. Placing any material or element next to one another generates a force field, which can be very unexpected and wonderful—like a safe camp, in fact. But that notion of safety also signals the privilege of authority, signage, the ability to grant permission. I think that bled into the line “In the quiet permission / I took my unit of heart and wondered if it was enough.”

I was also influenced by Joyelle McSweeney’s The Red Bird, which includes many different poems with the title “The Voyage of the Beagle.” This is something I stole from her—I actually have several poems titled “Safe camp.”

When did you know this poem was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished after all?

This iteration of the poem is probably finished. I read Benjamin Krusling’s Glaring many times around the time I wrote “Safe camp.” He has a gorgeous poem at the end of that collection that begins, “first there’s love…then there’s synchronized time.” And, in Triple Canopy, another poem that begins “it’s love , but there’s no time.” In both poems, variations on the lines are repeated in different orders. I asked Krusling, during a Q&A after one of his readings, about the relationship between these two poems, and he had this beautiful idea of a poem’s mutability—that it should never become an artifact, closed-off, museum-displayed. And that the most important things must be said many times in many ways. I’m interested in how this idea contrasts with the fixity that the page and publication provide.

Poems can also gather great force in their immutability, like the transformations produced by the repetition in chant. That’s what I was thinking about in the lines “An artifact // Gathered and became immobile, and even so / Changed year to year until its recognition fell to wind itself.” “Fell” then shifts to “felt” in the lines “I felt myself. I felt myself inhabiting it so I felt myself.”

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends or confidants? If so, what did they say?

I workshopped this poem with ten other poets one week after I wrote it. My notes from that session have fragments like “voice of poem hears ‘self’ and is startled outside of itself” and “memory as we perform it for ourselves, and disintegration,” “whirring in contained location.” There is something about an “animal mind” and reference to the “weight of mammal body” and the “underside of gristle.” There are recommendations for other poets, like Wyatt and Petrarch, who wrote poems including deer. Talking about this poem with those poets was like becoming aware of the aliveness of a shared mind.

Sara Gilmore is a poet and translator. She teaches at the University of Iowa and works as a phlebotomist.

Legal Considerations for Murals and Public Art

Murals and public art can significantly enhance an urban landscape, making art accessible to the entire community as well as serving as markers of community identity. But the creation and installation of these works of art comes with a complex web of legal considerations. Artists, property owners, and local governments must navigate the myriad legal issues and concerns applicable to public art projects. This article outlines some of the key legal considerations relevant to murals and other public art.

-

Copyright Ownership and Permission

One of the fundamental legal questions in public art is ownership. The first step in any public art project is to secure the rights to the wall or other space where the work will be placed and displayed. Before work begins, the artist or sponsoring organization and the owner of the property on which the art will reside must enter into a written agreement providing explicit permission to use the property for public art, among other issues, including:

- Any maintenance and repair obligations,

- Ownership of the work of public art (typically held by the property owner),

- Ownership of the underlying intellectual property (typically retained by the artist),

- Plans for what happens if the physical location or building is sold (does the agreement run to the new owner, effectively acting as an easement on the property?),

- Consideration of whether the property owner can alter or destroy the work,

- The specifications of the work of public art, including size, medium, and any content restrictions (i.e., no religious content, no sexual content, etc.),

- Agreement on how long the work will stay up, and

- The dates and times set for installation of the work, among other issues.

-

Photo by Mohan Nannapaneni from Pexels Moral Rights

Artists in some jurisdictions throughout the world have robust moral rights, which protect the artist’s personal and reputational interests in their work. In the U.S., though, moral rights are somewhat limited. However, in addition to copyright, thanks to the Visual Artists Rights Act (“VARA”) and common law, when it comes to public art, artists do have strong moral rights. These rights typically include:

- Attribution: The right to be recognized as the creator of the work.

- Integrity: The right to object to any derogatory treatment of the work, including destruction or mutilation.

Artists should be aware of their moral rights and negotiate their inclusion in licensing agreements when working on public art projects, with specific reference to VARA.

-

Zoning and Permitting

Public art installations may require compliance with local zoning laws and permitting processes. Many municipalities have specific regulations governing public art, which may include:

- Permits: Some cities require artists and property owners to obtain permits before installing murals or other public art. This process may involve submitting designs for approval to ensure they align with community standards.

- Zoning restrictions: Local zoning laws may dictate where murals or other public art can be located, particularly in historic districts or residential areas.

- Content restrictions: Different local rules may apply depending on whether the public work touts a business or brand or if the work is purely artistic.

Artists and property owners should consult local government websites or offices to understand the necessary permits and zoning regulations before starting a project.

-

Photo by Nilda Guzman from Pexels Funding and Sponsorship

Many public art projects are funded through grants, sponsorships, or crowdfunding. Each funding source may come with its own legal considerations:

-

Grant Requirements

When applying for grants, artists must adhere to specific guidelines that may include:

- Reporting requirements: Grantors often require detailed reports on the project’s progress and outcomes.

- Intellectual property rights: Some grants may stipulate ownership of the final work or require the grantee to license the work back to the grantor for promotional purposes.

-

Sponsorship Agreements

If a business sponsors a mural, a formal sponsorship agreement is highly recommended. This document should outline the expectations of both parties, including:

- Financial contributions: Clearly state the funding provided.

- Branding and promotion: Specify how the sponsor’s brand will be represented, if at all.

-

Community Engagement and Controversy

Public art is inherently a community endeavor, and engaging with local stakeholders is crucial. However, it also opens the door to potential controversies, especially if the artwork addresses sensitive social or political issues. Be prepared to engage on these matters. Art is subjective and is unlikely to please everyone.

-

Image courtesy of Canva Community Input

Some cities require public input for art projects, particularly those funded by taxpayer money. This process may involve public meetings or other processes providing public input. Failure to engage the community may lead to backlash, vandalism, or legal challenges.

-

Controversial Works

Artists must consider the potential for controversy. While artistic expression is protected under the First Amendment, local governments may have the authority to remove or cover works that are deemed offensive or inappropriate. Artists should discuss potential content sensitivities with stakeholders to minimize the risk of backlash.

-

Vandalism and Maintenance

Public art is often exposed to the elements and potential vandalism. Legal considerations regarding maintenance and restoration can arise and should be addressed in the agreement between the artist and the property owner.

-

Liability Issues

Property owners and artists should clarify liability responsibilities in their agreements. For example, if a mural is vandalized, who bears the cost of repair? Who is liable if an individual brings a right of publicity claim because they are depicted in a mural with an arguably commercial message without their consent? These details should be explicitly outlined in the agreement between the artist and property owner to prevent potential misunderstandings.

-

Preservation Laws

Some public artworks may fall under preservation laws, especially if they are deemed historically or culturally significant. Artists and property owners should be aware of any legal protections that may impact maintenance, restoration, and removal of the work.

-

Insurance and Liability

Artists and property owners should consider obtaining insurance to protect against potential liability associated with public art projects. This may include:

- General liability insurance, which covers injury or damage that occurs as a result of the art installation.

- Property insurance, which protects against damage to the mural or public art itself.

-

Indemnification Clauses

In contracts, indemnification clauses can protect one party from liability resulting from the actions of another. For instance, if the artist’s work leads to damage or injury, the property owner may seek indemnification from the artist. Indemnification provisions must be carefully considered.

Conclusion

Murals and other public art offer significant benefits to communities, but also come with a range of legal considerations. From ownership and copyright to government permitting and community engagement, artists, property owners, and other stakeholders must navigate these complexities carefully. By understanding and addressing these various legal issues, public art can thrive and be a significant source of community pride.

________________________

Authors bio:

Co-founders of intellectual property law firm Crown® LLP, Elizabeth J. Rest and Owen Seitel have a passion for Advising Creativity®. Elizabeth is a brand builder and portfolio protector, focused on trademarks and copyrights, and Owen has more than 30 years of experience with commercial endeavors, transactions, and disputes involving intellectual property and broader business matters. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].

This Artist Creates Incredible Sketchbook Sized Replicas of Gothic Architecture

Alex Pantela is an incredibly talented artist from Leeds who focuses on patience and attention to detail. Truly, his shop for artwork is even called The Store of Detailed Drawings. And that’s exactly what you’ll find there, immaculate handdrawings of Gothic, Renaissance and Victorian architecture that gets every detail right. That’s because Pantela is willing to take his time. Although his pieces are sketchbook sized, Pantela puts up to twenty hours into his drawings, making sure to catch every last inch of the architecture he’s recreating on paper.

Throughout Alex Pantela’s Instagram, you can see his work as it goes through stages of sketch and levels of detail until, in many cases, you get to see the finished product held up to the real thing and marvel at the uncanny resemblance shown to scale. Pantela’s black and white pieces are all finished in black ink and feature deft shading contrasted with the bold features of his subject. It’s amazing to see Pantela’s hand holding an exact miniature drawing of Westminster Abbey directly in front of the real Westminster Abbey as it pokes out over the sketchbook. Alex Pantela does this for many landmarks including Barcelona Cathedral, King’s College and Arco de Triunfo. He works in large, building scale as well as capturing the finer details of a building by focusing solely on a door handle or the ornamental iron work across a window. His ability to draw things as they are, strives towards the Platonic ideal of representation. Not only can I imagine having his skills, I can hardly imagine having his focus. It’s amazing, the kind of art that makes you look at the details of the world around you with fresh eyes.

Ice-T: ‘Anybody that thinks controversy is a way to make money, it’s not. You need lawyers!’ | Ice-T

Was there ever a moment during the furore over Cop Killer when you were feeling the heat and/or questioning yourself over releasing it? Sophisticles

I never really questioned myself, but the heat came when they started sending bomb threats to Warner Bros. I threw the rock, that’s my heat. But when other people could get hurt, that’s nerve-racking. But I got news for people: anybody that thinks controversy is a way to make money, it’s not. You get a lot of buzz, but now you need lawyers. So don’t just say something stupid and then back-pedal – if you’re going to say something, stand on it.

Is Body Count in the house? IvanBunin77

Yeah, definitely. We’ve been back in the house ever since [2014’s] Manslaughter. Once we connected with [producer] Will Putney we caught our second wind. We had a low moment because we lost some band members and that’s going to hurt any band, but we got our groove back.

How did it feel to put yourself in the shoes of a psychopath for your new album’s lead single? VerulamiumParkRanger

That song sounded like I imagine a psychopath’s brain would sound: very erratic, very crazy. One of the things I’ve always loved to do is become people in my songs – like rapping from the perspective of a cop killer. So I just sat back and I tried to think like a psychopath. It wasn’t really hard.

What was it like working with Motörhead for Born to Raise Hell? Did you keep in touch with Lemmy? AllThisRunningAround

The fact Lemmy even knew who the fuck I was was dope. Lemmy was cool, but I really didn’t get to kick it with him. But the fact that he’d requested me for the track – that’s all I needed to know. He was a legend.

Usually our collabs come from knowing people and being friends. Like Amy Lee from Evanescence came about because Vince [Price, bass] was working with them on the road. Having Dave Gilmour on the new record was a long shot, though. It started with me wanting to do Comfortably Numb, because I believe right now we are all comfortably numb – you can watch someone get set on fire on television and then just start watching the football game. We did the song and Pink Floyd’s publisher just said “no, no way”. My manager reached out to David Gilmour, and the next thing we get a call saying: “I want to play on the record.” I’m sure there’s purists that might hate the song, but fuck them.

When you founded Body Count, a Black man performing heavy metal was pretty rare. Have you enjoyed the growing crossover between hip-hop and heavier music in recent years, and the increasing diversity in genres such as hardcore and metal? MrPleebus

I didn’t really care, I was just trying to do me. Of course, yes, it feels good to see the genre merge and change, but that wasn’t my agenda. My agenda was simple: to play in a band with [guitarist] Ernie C. Touring in Europe with Public Enemy, I’d noticed the kids would mosh off of fast rap and that’s what sparked the idea to do Body Count, to do a fast rock band. It wasn’t like, “Let’s get Black people in.” It was just … I’m going to do this shit.

On your debut Lollapalooza run you regularly performed Sly & the Family Stone’s Don’t Call Me N*****, Whitey with Jane’s Addiction. Has the time passed when Black and white artists can duet on such a culturally weighted song? McScootikins

I don’t really fuck around with people that are worried about getting cancelled. Somebody once said: “Ice-T is the only person who does things that totally jeopardise his career just to stay awake.” But if we’re not going to push the line, then why even make the song? It should rub some people wrong.

Do you have Charlton Heston pompously reciting Body Count lyrics – as he famously did at that Warner Bros shareholders meeting – as your ringtone? Haigin88

Fuck him. You know what we did? We made a gold record for him. We thanked him for talking shit because it got us a lot of attention.

How did you go from rapper and rock musician to Law & Order: Special Victims Unit? EnriqueCortesRello

My first acting job I had to play a cop for New Jack City and I was dropping an album called OG Original Gangster – I thought it was career suicide, but people accepted it and none of my peers had anything bad to say. They called me to do four episodes, and it just kept on giving, 25 years later. Hip-hop was doing this paradigm shift away from acts like me, Public Enemy and Ice Cube into this weird other world where I wouldn’t have survived. So maybe it was like a lifeboat pulling up next to me. Like, OK: time for you to change your main hustle. It’s been a good ride, and it keeps me contained – when you’re a musician and only a musician, you got a lot of free time, and that free time can get you in trouble.

How much do you miss [Law & Order co-star] Richard Belzer? CoveRoad

I really miss Rich. He passed the same week I got my star [on the Hollywood walk of fame], so that was a bittersweet moment. Belzer was my OG. He was the guy who showed me the ropes. He taught me it’s not who has the most scenes, but who has the most memorable scenes – when you’re in, make sure those scenes are memorable.

I thought you were excellent in [2001 crime drama film] ’R Xmas. What was it like working with Abel Ferrara? Drea de Matteo seemed to suggest it was a chaotic yet creatively satisfying shoot? penny_lane00

Abel Ferrara, he’s a wild man, he was all over the place. Schoolly D worked with him on King of New York, and he told me: “Abel is a great guy, he taught me a lot about the film business. Although he did also introduce me to heroin.” Then he says – and this is my favourite quote: “One thing about Abel is he will never lie to you. Unless he’s lying to you.”

So, anyway, after the movie’s done, I say: “Abel, I want to go to the screening.” I show up at his apartment on the Lower East Side, thinking we’re going to a place to see the movie. He’s got a little TV with a VCR at the bottom of it, sitting on his kitchen table. His boy is laying on the couch with his sock hanging off his foot, and Abel’s in the back with some chick. He tells me, “The movie’s right there, just watch it.” I say, “On this screen?” And he says, “Yeah, that’s how most people are going to see it anyway.” So I sat in his kitchen while he was doing who knows what in the bedroom, his boy’s on the couch asleep, and I watched the whole movie right there in a crazy Lower East Side apartment. So my experience with Abel is just as wild as anybody else’s. But the movie came out dope, and I would work with Abel again. He’s a rite of passage if you’re a New York actor.

What were your first thoughts when you read the script for Johnny Mnemonic? arashikage

William Gibson wrote that, and I knew he was an incredible sci-fi writer. Keanu Reeves was just coming off Speed, so he was hot as fuck. Henry Rollins and Dolph Lundgren were in the movie. Plus the offer was good, so I really didn’t give a fuck about the script. It was a fun ride, and I’m proud of that movie.

I became good friends with Henry Rollins when we were on Lollapalooza together. I learned a lot about being a lead singer from seeing him come on stage barefoot with “Search & Destroy” on his back. I was like, this motherfucker’s bad – I gotta be bad like him. It was a sense of just being true to yourself: to be and do what the fuck you want, because if you’re really a leader you dictate what the fucking culture is, you don’t let the culture dictate to you.

Where do you stand on AI technology? Should there be limits? RDMiller

I don’t think there’s anything we can do to stop technology coming to eat us. Have you ever seen a movie about the future where it was happy?

Helsinki Design Week 2024: Anni Korkman on the Festival’s Mission of Inclusivity and Sustainability

Anni highlights the transformation taking place in the design field, emphasizing a shift from focusing solely on end products to exploring the design processes themselves. “This year, the focus is on design processes: how ideas are developed, how materials are used and reused, and how design can reflect a deep respect for the environment, especially considering the current geopolitical and climate crises”, she explained. Her vision centres on the idea of creating design that serves the city and its people, emphasizing that it’s not just about making more but about making better for the community.

Rethinking the festival’s format was also on Anni’s checklist going forward. “It’s important to reconsider and redefine the format of the event, suggesting that such festivals should tell stories not only about designers but also about their practices.” This perspective not only encourages a broader conversation on the impact of design, but explores its significance not only on a local level but also within a global context. “It’s almost an invitation to understand what it really means to be a designer today—a journey that combines personal growth with a deep sense of social and environmental responsibility.”

artphotocollector:Have Tuk-Tuk will travel… “Let serendipity be…

Have Tuk-Tuk will travel…

“Let serendipity be your muse…”

In a new Broadway revival of ‘Yellow Face,’ Daniel Dae Kim explores racial identity

A revival of the play “Yellow Face” will make you laugh despite the fact that it examines some hefty topics: cultural appropriation, racial identity and representation in the theater, to name just a few.

The play written by David Henry Hwang centers around a fictionalized playwright named DHH, who has made a name for himself fighting against yellow face — the practice of using white actors to play Asian roles — in the theater. That mirrors events from Hwang’s real life: In the 1990s, he led the protest against “Miss Saigon” for casting a white British actor (Jonathan Pryce) in a lead role, playing a Eurasian character.

In “Yellow Face,” DHH (Daniel Dae Kim) runs into a problem when he accidentally does the same: He casts a white man in a role he wrote for an Asian actor. Instead of admitting his choice, DHH tells the world his actor is a Siberian Jew, and Siberia is in Asia.

The whole thing comes to a head when reporters and the government start investigating Chinese Americans for spying and money laundering. That includes the actor and DHH’s father, a wealthy businessman who loves the U.S. – but does the U.S. love him back?

“Yellow Face” first premiered in 2007 at the Public Theater, and the revival opened last week to rave reviews. Hwang and Kim joined Alison Stewart on a recent episode of WNYC’s “All of It” to discuss racial identity, Rachel Dolezal, ambitious flops and more. An edited version of their conversation is below.

Alison Stewart: David, I’ve heard you describe “Yellow Face” as a mockumentary, like “Spinal Tap.” Some things are true, some things are turned up to 11, some things are false. Let’s start with the true stuff. What made you decide to protest “Miss Saigon”?

Hwang: I owed my career to an earlier yellow face protest, people who protested in front of the Public Theater 10 years earlier, which led Joe Papp [founder of the Public] to start to look for an Asian playwright, and that was me. And so when the “Miss Saigon” protests came around, it just felt like someone had paid it forward to me, and I needed to be part of that.

This was all happening when you were starting out in your career. What did you think about the protests, Daniel?

Kim: I remember thinking that they were necessary because, as a young Asian actor, I knew what a dearth of opportunities there were for us. And when you have a chance to play a lead on Broadway, and that is no longer there for these kinds of reasons, it’s problematic. At the same time, I also sympathize with my friends, who also said, “Well, when else are we going to be on Broadway in a supporting role, other than in a show like ‘Miss Saigon?’”

It represents one of the few opportunities we have to do anything, even in the ensemble. I had some mixed feelings about it, but there’s no question that David was on the right side of history there.

It was a big story. The point was made, and it was bypassed. The play came to Broadway. In response, you set out to write “Face Value,” with a white actor cast in the Asian role, and it was originally a farce. What part of it made you think, “Oh, I’ll write a farce?”

Hwang: After the protest, which was sort of an early culture wars event, and being caught in the middle of that and arguably being a little bit canceled by mainstream media and opinion, I felt traumatized, and I needed to process that. So I decided to write a comedy of mistaken racial identity about the question: What does it really mean to play a race, to play one’s own race? But I wrote it as a door-slamming farce and it became one of the biggest flops in Broadway history.

You say that with such joy, in a way. When you think about it now, would it be a flop now?

Hwang: Oh, yes. I can have some joy about it, because after 20 years, the story has a happy ending.

What?

Hwang: Well, in the sense of taking that concept again – a comedy of mistaken racial identity – and coming up 15 years later with “Yellow Face,” a different way to approach the same idea.

Daniel, in “Yellow Face,” your character is DHH. How would you describe him?

Kim: He is a man who is wrestling with this idea of who his authentic self is and what are the masks that he’s developed over the years to try and protect who he really is, and what does it require for those masks to come off? Even though he has the best of intentions, there are other parts of his personality that serve as obstacles to him being his true self.

What are DHH’s flaws?

Kim: I would say a little bit of hubris, a little bit of narcissism, a little bit of inability to acknowledge mistakes until the consequences get so high that he’s forced to acknowledge them.

Hwang: I feel like Daniel’s being a little kind because I’m also in the studio, but I would say a lot of hubris, really, and really trying to protect his reputation as an Asian American role model after making mistake after mistake after mistake in this play.

Are you really self-aware? I mean, when you write something like this, you had to write your own flaws into your play.

Hwang: There are a lot of autobiographical works. It’s just that usually, the author doesn’t name the main character after themselves. In this case, I found, well, once I did that, I really needed to make him a character. So yes, there are ways in which he’s like me, and then there are things that happen because it helps the plot and it helps the character have an arc and some redemption at the end.

Kim: I give David a lot of credit for not making himself a very shiny hero in his own work. He’s very human. More than human. I’m not sure what that means exactly.

People get it.

Kim: He presents himself as the butt of many of the jokes in this piece. It takes a very healthy sense of self to allow people to laugh at you openly.

Apparently, this script has 30 minutes knocked off the length from the original 2007 version. Intermission is gone. What did you do?

Hwang: After a certain amount of time has passed, both Leigh Silverman, the director, and I were able to look at the piece with a little more objectivity. We had originally intended it to be an intermission-less evening, but the show was just too long. And I think most of the changes that have happened between 2007 and the ’24 version just involved cutting and shaping and polishing. There was stuff that we got rid of and then we didn’t miss it.

In “Yellow Face,” DHH casts a white actor to be the lead in his play. It’s pre-Internet, so he can’t really check him out. Why do you think DHH goes along with the white actor? Why doesn’t he just say, “Wait. No, we need to stop.”

Kim: I think for him, there’s too much at stake. As David mentioned, there’s protecting his reputation, especially as someone who protested the casting of a white actor previously. And again, hubris, this idea that he can get away with it if he chooses to make these choices. I think we’ve all been in positions where we have to make choices and sometimes the honest choice is the one that comes at the greatest cost.

Well into the play, DHH is having a fight with the white character, and you call him a racial tourist. What does that mean to you?

Hwang: Ethnic tourist. The line is, “You come in here with that face of yours and everyone falls at your feet, you ethnic tourist.” In the play you have the white actor, Marcus. David gives him an Asian identity, which is invented, but then Marcus runs with that and becomes an Asian activist of the sort that David is not willing or able to be at that point in the story. David is saying he just skims the cream and gets to have the advantages without any of the real consequences.

Kim: Which I think is very funny, too, because he’s criticizing Marcus in that moment for a mantle he could be taking, and he’s criticizing the very creature he created.

It’s interesting because the white actor is saying, “I like being part of something.” “As a ‘Eurasian’ actor, I can be part of this.” When you think about it, is he wrong?

Kim: No, absolutely not. I think that’s what makes this play so human and universal. We all want to find a place of belonging. We all want to be validated in some way and just because you’re of one particular race or another race doesn’t change that need. We all are looking for our home and our community, and I think that’s what makes Marcus sympathetic.

Hwang: I would also add it’s complicated because his need to be part of the community, or his justification, is based on a lie. He’s not actually a mixed-race Asian. Hopefully, it gives the audience stuff to chew over and discuss after the show.

I wrote “Rachel Dolezal” across the top of my notes. She was a white woman who portrayed herself as a Black woman, headed the local NAACP, and there was a big hoo-ha. I’m wondering what you thought about that.

Hwang: It happened after the original production, and so I guess I thought in the original play, “It seems likely to me that this sort of thing is going to happen as we move forward as a more multicultural and more diverse society, and that passing might end up going both ways.” So yes, when Rachel – I don’t even know how to pronounce her last name — came around, and there are a couple of others that have come up since, particularly in the publishing world, it’s been, I don’t know, either gratifying or horrifying.

Kim: By the way, you don’t have to not be a member of a particular ethnic group to start using the emphasis on identity and inclusion as a mask. There are a lot of Asian Americans who never cared about this issue until very recently, and then suddenly they’ve taken up the mantle and the question is: How genuine is that or how much is that just going along with a rising tide?

Then to add another layer to it, in your cast, you have people playing against type. You have a woman playing a man. Marinda Anderson plays Jane Krakowski. Kevin del Alguila plays Ed Koch. How does this set up the audience to maybe understand the play better?

Hwang: Well, in the original production, the casting was essentially binary. It was just Asians and white people. And because society has moved on in some good ways, by the time we get to 2024, we wanted this production to be more inclusive. Then there was the question of: Okay, what does it mean – I mean, now we’re pretty used to actors of color playing white people.

“Hamilton” certainly has mainstreamed that, but what will it mean for actors of color to play other characters of color, not of their own ethnicity? We try to be very mindful about the choices that we made. But to me, in a good and fun way, maybe it pushes the envelope a little more and it’s something that people can talk about, too.

Daniel, what is DHH having a hard time understanding about his dad?

Kim: Well, I think as a second-generation immigrant or a 1.5-generation immigrant, there are expectations, I think, speaking as a 1.5-generation, there are expectations that we could have of our country that sometimes recent immigrants do not have. What I mean by that is, for instance, my parents, when they came here, they thought of themselves as visitors to this country. They didn’t think to question the issues that are problems in the country as much as to say, “We’re lucky to be here. Take what you’re given and work hard. Put your head down.”

As a person who’s grown up with the issues in our country, there’s more of a sense of ownership, and I’ll just speak for myself. And so when I see problems, I want to raise my voice and say, “This place is not perfect. I 100% choose to live here and love this country, and at the same time, I can be a voice that helps shape this country.”

When I went to the theater on Saturday, I saw a lot of Asian Americans in the audience everywhere I went. What did they get to see?

Kim: First of all, they get to be entertained and I love that most of all because our job, first and foremost, is to entertain. When there are people in the audience who wait for me backstage or outside the stage door and they say to me, “This is the first Broadway show I’ve ever seen.” That is one of the biggest compliments that I can receive because it tells me that we’re expanding the number of people who come to the theater.

I think that couldn’t be more important for a new generation of theatergoers to know that that’s part of the entertainment landscape. I would also say that I think it’s really important for young Asian Americans in particular because this show is about our history. And those who don’t know who David Henry Hwang is and don’t know what the controversy around “Miss Saigon” was, it’s important that they do because very often we are considered the silent minority, that we do not speak up for ourselves.

We did have pioneers all throughout history who did that and there are very necessary chapters of our history that are included in this play. By the way, this is not just Asian American history, this is American history. I think if it spurs people to say, “Who was Wen Ho Lee?” then I think we’re serving a dual purpose.

Did you want to respond?

Hwang: Well, it’s needless to say, we are very fortunate to have Daniel, because there are a fair number of Asian Americans – and people in general – who come to see Daniel. Broadway is looking for new audiences, and that isn’t going to happen as long as we keep appealing only to a narrow slice of the demographic. Pieces like “Yellow Face” but also pieces about other communities that have been marginalized in the entertainment world, are so important in expanding our audiences as well as our definition of what constitutes the American theatrical canon.

“Yellow Face” is playing at the Roundabout Theater on 42nd Street until Nov. 24.