An Art Lover’s Book List

12 inspiring books to gift to the art-friendly people in your life this holiday season.

When considering gift ideas, a book—and not the digital kind, but a printed book with weight and texture that you can feel in your hands — will never go out of style. You can wrap a book in colorful paper and tie it up with ribbon. For artists and art lovers—and the parents or grandparents of future art appreciators—books remain a popular gift, both to give and receive. To make your holiday shopping easier this year, we’ve put together a list of book suggestions to suit all sorts of readers on your shopping list!

Art Books for Youngsters

A reading list for little folks with creative minds!

The Art Book for Children (Phaidon, 2024) is serious about art and assumes the parents or grandparents or other adults who buy this book for their kids are also dedicated to the subject. Phaidon, one of the most esteemed publishers of books on art, has released a newly revised edition of this popular series, which first published 20 years ago. It includes beautiful reproductions of iconic works of art like self-portraits by Frida Kahlo (1907–54) and Botticelli’s Primavera (1482). This is a book intended for adults and kids to read together. The publisher targets the content toward 7– to 12-year-olds, but adults will also find it fascinating and informative. It’s a gift under $25 that can make a lasting impact on a child’s imagination.

Dot, Scribble, Go (Chronicle Books, 2024) is a new hands-on activity book for kids by Herv Tullet, who has authored more than 80 books on art. Tullet starts with the premise that it’s part of human nature to want to make marks on paper (or any other surface for that matter), and that those marks, dots and scribbles can be a gateway to the imagination. His lighthearted and whimsical approach, while targeting the kindergarten and preschool age group, might also encourage adults to think about what it means to make art. At under $20, this gift is both fun and affordable.

What Is Color? The Global and Sometimes Gross Story of Pigments, Paint, and the Wondrous World of Art (Roaring Brook Press, 2024), by noted author and illustrator Steven Weinberg, is a delightful and educational mash-up of science, art, history, geology and anthropology, all in the service of helping us understand and appreciate the origins and meaning of color in our lives. Although targeted to 6- to 10-year-olds, you may want a copy to keep for yourself.

Books for Art History Lovers

Art history is a slow-moving story. These books are recent, but not brand new, and some are classics that have held up over time.

Traditionally art history has been taught chronologically, and most often from a European, male-dominated perspective. Thematically arranged by the staff at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City, Art = Discovering Infinite Connections in Art History from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Phaidon, 2020) uses more than 800 objects from the museum’s own collection to shake up our thinking about what art is and how it’s integrated in our lives. At $75, this is a high-end gift book that can be passed on and used as reference for years to come.

Women, Art and Society (Thames & Hudson, 2020), by author Whitney Chadwick, was one of the first books to present art history from a woman’s point of view. Now in its sixth revised edition, it reexamines the impact that new feminism has had on the way art history is taught and the way art is collected and exhibited in museums. It includes lots of color images of work by women artists from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance to today. Curator and professor Flavia Frigeri, a rising star in art history circles and a curator at the National Portrait Gallery, London, is an important contributor. A paperback edition is available for under $25.

Giorgio Vasari (1511–74) was an Italian Renaissance artist and biographer best known for the publication of The Lives of the Artists (Oxford World’s Classics), which is considered the bedrock reference for all art historical writing that has followed. This translation, re-issued in 1998, is a must-read for anyone interested in the way some of the greatest artists of the Renaissance period lived and worked. It includes details of the lives of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Michelangelo (1475–1564), among others. Now also available in kindle, audio and paperback editions for as little as $5, it could make a useful gift for the budding art historian in your life.

Books for Your Artist Friends

For your friends who know their way around a paintbrush, here are few instructional and career-minded reads to encourage their art practice.

Become a Great Artist: Gain Confidence in Your Art, Find Your Creative Voice and Launch a Thriving Career (Page Street Publishing, 2024) is a new book by Kristy Gordon, an accomplished painter and adjunct professor at New York Academy of Art. With a goal of helping artists overcome some of most challenging issues blocking their path to success, this is a guidebook for practicing creatives in all media. Learn how to develop long-lasting habits, incorporate techniques from prolific artists into your craft, pitch to art galleries, make a career from your art, and more! Available in kindle and paperback for under $25, this gift could be a game-changer for artists who want to grow.

Artists Lynn Sures and Michelle Samour partnered up to write Radical Paper: Art and Invention with Colored Pulp (The Legacy Press, 2024), a 440-page hardcover presentation of the many ways paper pulp has been used in art-making over the years. It includes intimate looks at the studio practice of many artists who’ve explored the varied uses of paper as a surface and as a medium, inventing new methods of art-making. It’s a pricey book, at $75, but includes more than 200 works of art by 73 groundbreaking visual artists, making it an exciting resource for artists, curators, collectors, art historians, and anyone who finds inspiration in the endless possibilities offered by paper.

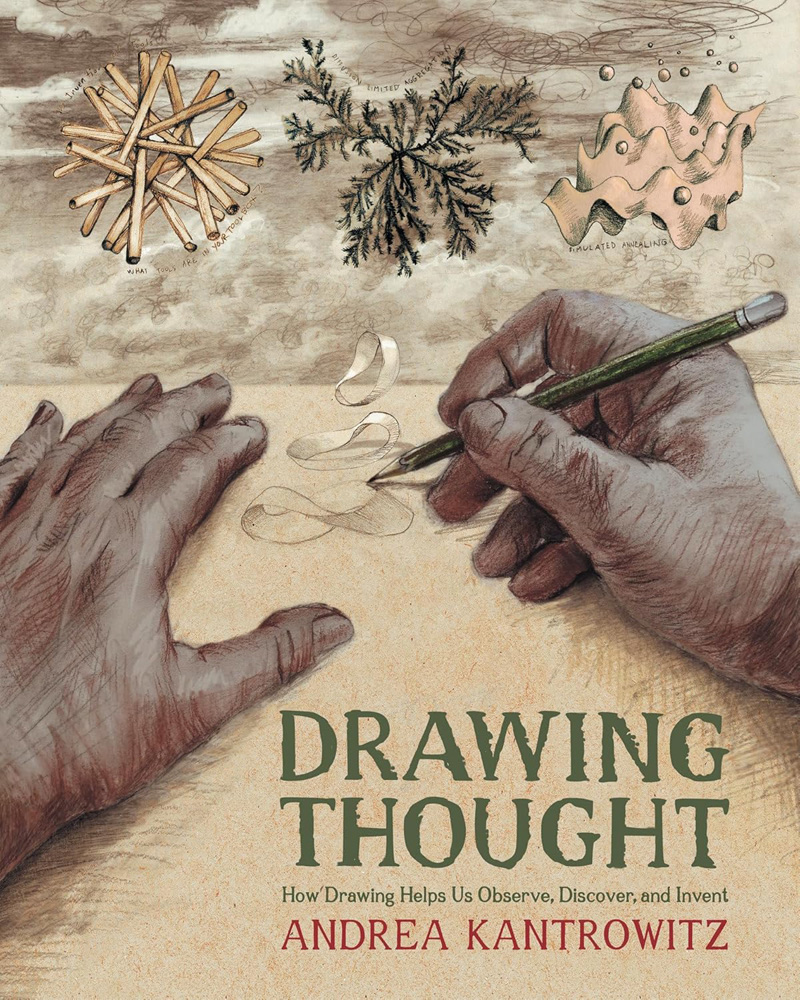

Drawing has been an expressive outlet and a path of creativity for humans since we first traced our hands on cave walls. In Drawing Thought: How Drawing Helps Us Observe, Discover, and Invent (Penguin Random House, 2022), author Andrea Kantrowitz, who holds an MFA in Painting from Yale and was a teaching-artist in the New York City public schools for many years, encourages readers to explore the development of their own ideas through the exercise of drawing. A paperback edition is available and priced under $25.

Artsy Books for Anyone

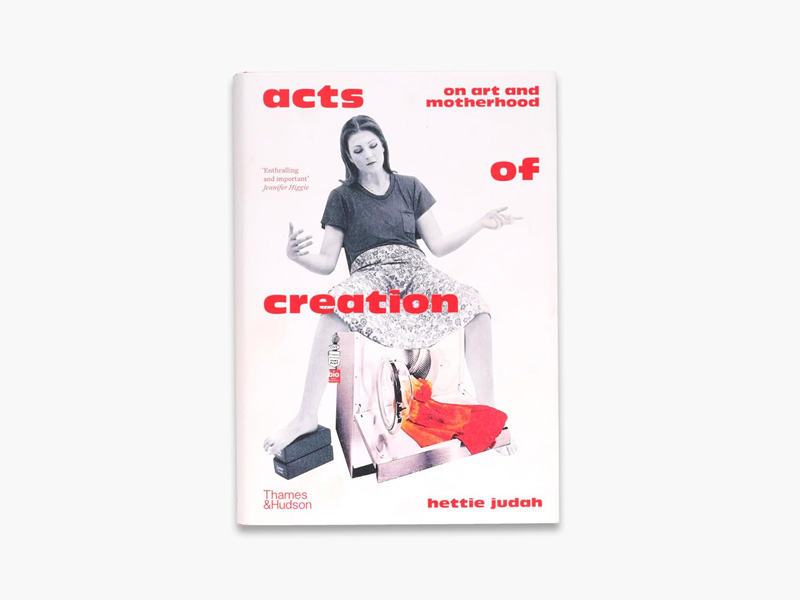

Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood (Thames and Hudson, 2024), by author/critic Hettie Judah, explores the image of motherhood created by artists throughout art history, while also delving into the real-life issues artists face in becoming parents. Judah includes the thoughts and work of modern and contemporary artists, such as Berthe Morisot (1841–95), Barbara Hepworth (1903–75), Jenny Saville (b. 1970), Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907), Betye Saar (b. 1926), Suzanne Valadon (1865–1938), Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1953), and many other artists whose views of motherhood (positive, ambivalent or outright hostile) infused their work. Mothers and fathers alike who are juggling creative careers while raising a family will find much to ponder in this groundbreaking book. A hardcover edition is available for under $40.

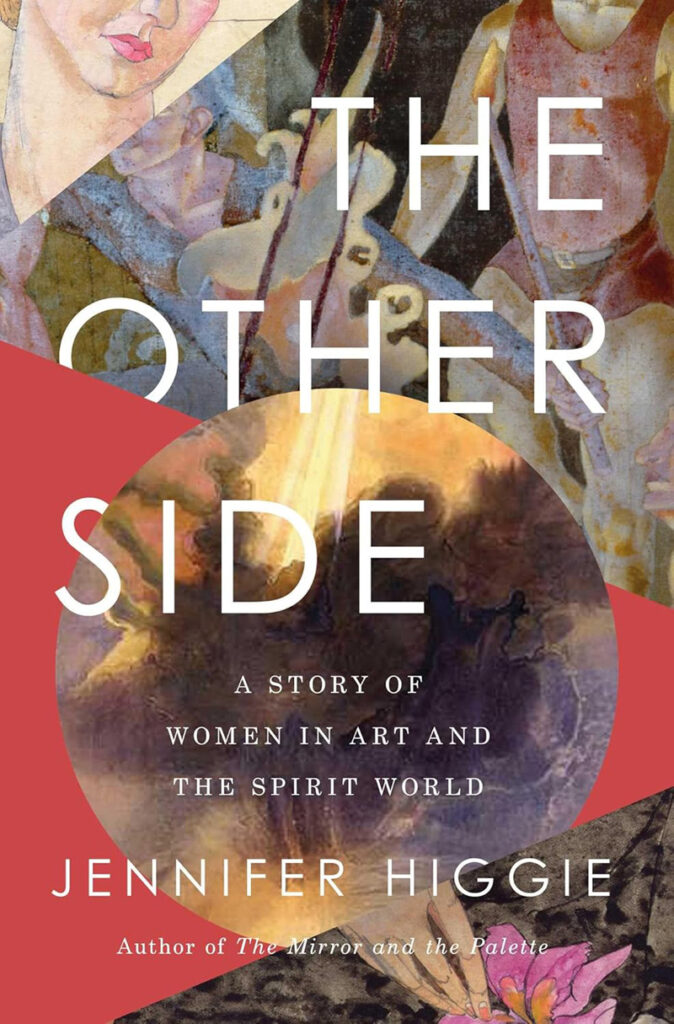

The Other Side: A Story of Women in Art and the Spirit World (Pegasus Books, 2024), by Australian writer Jennifer Higgie, explores the lives of previously marginalized women, like the early 20th-century Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), who has recently seen a surge of new interest, causing her work to be reevaluated by museums and collectors alike. Higgie, who also wrote The Mirror and the Pallette: Rebellion, Revolution, and Resilience–Five Hundred Years of Women’s Self Portraits, is an author whose work has changed the way I perceive the history of art. The Other Side discusses the solace of ritual, the impact of myth and the relationship of spiritualism to feminism in art, giving readers much to ponder. A hardcover version is available for under $20.

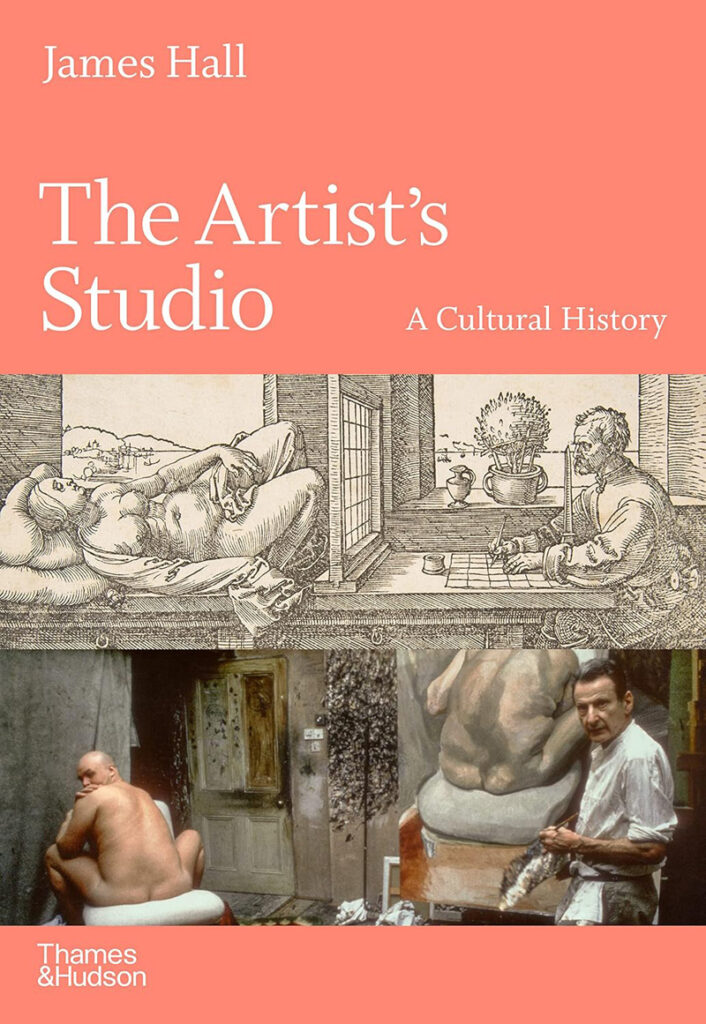

In The Artist’s Studio: A Cultural History (Thames and Hudson, 2023), author James Hall traces the history of art-making from the Renaissance to the present day by taking readers inside that mythical place, an artist’s most private domain—their studio. A color photo of the nearly unimaginable chaos of Francis Bacon’s (1909-1992) London studio, taken in 1998, precedes the introduction—a hint to the many surprises to come. The book provides a unique way to think about the way artists live in their own time. A hardcover edition is priced under $25.

About the Author

Cynthia Close earned an MFA from Boston University and worked in various art-related roles before becoming a writer and editor. She is a regular contributing writer to Artists Magazine.

Paintings by children from China and France celebrate diplomatic ties – SHINE News

Paintings by children from China and France celebrate diplomatic ties SHINE News

Source link

Favourite Films of 2023 | The Seventh Art

Each passing year seems objectively, measurably worse than the one before, at least on a world-historical level, unveiling new lows for evil, stupidity, hypocrisy and tyranny across the globe. I’ve done nothing to change any of it, but I’m glad that, unlike me, there are people who aren’t desensitized, wilfully blind or paralyzed by analysis fighting the good fight. More power to them.

The blog hasn’t been terribly active this year. In February, I started a curatorial section on the site to showcase work from up-and-coming filmmakers, but I haven’t been able to keep it up at a rate I would like. I hope I can resume the section in 2024, even if at irregular intervals.

The primary reason for the inactivity is that I made my first foray into festival programming this year. I was on the South Asia selection committee for the Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival (October-November 2023) as well as the upcoming Berlin Critics Week (February 2024). Both assignments meant six months of intense, non-stop film viewing. A revelation from my time on the MAMI committee is that South Asian cinema is absolutely exploding, with crazy, ambitious works emanating from unlikely corners of the subcontinent, made by passionate individuals with little institutional or industry connections, with private resources unrelated to traditional channels of funding. It was truly an eye-opening discovery. Exciting times ahead for South Asian cinema.

For the first few months, however, I had a voluntary, almost systematic immersion into the history of avant-garde film, especially works from North America. I watched over 700 titles, long and short, canonical and lesser-known. I complemented this with reading books on the subject: Sheldon Renan, Amos Vogel, P. Adams Sitney, A.L. Rees, Stephen Dwoskin, William C. Wees, Jonathan Rosenbaum. But the single most instructive source was Scott MacDonald’s A Critical Cinema (1988-2005), five volumes of magnificently detailed interviews with avant-garde filmmakers from across generations and geographies. These exhilarating, demanding months of watching and reading truly felt like a substantial phase of my cinephile education.

It was also the year I published by second book, Moving Images, Still Lives, a lavishly illustrated monograph on Amit Dutta’s film Nainsukh (2010), published by Artibus Asiae of the Museum Rietberg Zurich. (Readers in India may consider buying a copy off Amazon, where a very, very limited number is on sale.) This book was an opportunity for me to undertake a different kind of writing — less spontaneous but more scholarly, with arguments propelled more by citations than passion. Also, until now, my references in visual arts were almost entirely European and American. Writing on Nainsukh meant researching into Pahari miniature painting and the world it issues from — an exposure I’m really grateful to have gotten.

I had no greater experience this year than watching Lijo Jose Pellissery’s Nanpakal Nerathu Mayakkam (2022), a work I would without hesitation count among the ten or so finest films ever made in India. Heck, had I seen it a few months earlier, it would’ve made it to my ballot for Sight & Sound’s all-time poll. With age, I encounter fewer and fewer films capable of shaking me up the way Pellissery’s masterpiece has. It is one of the great spiritual works of the cinema.

I didn’t see as many commercial releases as I would’ve liked, and the ones I did weren’t too inspiring. I’ve consistently had problems with Martin Scorsese’s films set in cultures foreign to him, and despite the thrilling opening hour, Killers of the Flower Moon felt crippled by the same respectful distance that hamper Kundun (1997) and Silence (2016). I found Oppenheimer and Barbie equally tedious, both movies arriving with their own halo. Among Indian releases, I found things to like in several works, such as Thankam, Maaveeran, Kaadhal: The Core, Chithha, Jigarthanda DoubleX, Animal, Viduthalai Part 1 and Haddi, but few were convincing in their entirety. So the list below is entirely composed of titles I saw at festivals or as part of my programming work. They all had their world premieres in 2023 at the festivals mentioned. Needless to say, this is a somewhat arbitrary list, and I can count about seventy other films that could be here instead. But I’ll spare you the hand-wringing. Happy new year.

1. Kayo Kayo Colour? (Shahrukhkhan Chavada, India)

Rare are Indian films centred on marked Muslim characters, and rarer are those that don’t employ these characters primarily as objects of violence and social injustice. In Shahrukhkhan Chavada’s tender, trailblazing Kayo Kayo Colour?, Muslim bodies exist in an existential autonomy, untouched by dramatic aggression and capable of accessing a whole range of human experience. Chavada’s film depicts the everyday life of an extended working-class family in a Muslim quarter in the outskirts of Ahmedabad on a historic day. We see a woman waking up early to do household chores, her husband trying to procure funds to buy an autorickshaw, their children playing gender-segregated games. Public spaces come alive with shrieking middle-schoolers, a mother folds clothes with a daughter who has made it out of the ghetto, a girl sleeps over at her grandparents’ place—routines that become electrifying expressions of communal life. With striking passages of dead time and non-narrative digressions, the film creates space for its characters to breathe freely, to simply be. This is a work that opens up a new way of looking at life in India. In its wonderous gaze at the world, in its incredible generosity, in its profound humanity, there’s little I’ve seen of late that comes close. [World Premiere: International Film Festival Rotterdam]

Rare are Indian films centred on marked Muslim characters, and rarer are those that don’t employ these characters primarily as objects of violence and social injustice. In Shahrukhkhan Chavada’s tender, trailblazing Kayo Kayo Colour?, Muslim bodies exist in an existential autonomy, untouched by dramatic aggression and capable of accessing a whole range of human experience. Chavada’s film depicts the everyday life of an extended working-class family in a Muslim quarter in the outskirts of Ahmedabad on a historic day. We see a woman waking up early to do household chores, her husband trying to procure funds to buy an autorickshaw, their children playing gender-segregated games. Public spaces come alive with shrieking middle-schoolers, a mother folds clothes with a daughter who has made it out of the ghetto, a girl sleeps over at her grandparents’ place—routines that become electrifying expressions of communal life. With striking passages of dead time and non-narrative digressions, the film creates space for its characters to breathe freely, to simply be. This is a work that opens up a new way of looking at life in India. In its wonderous gaze at the world, in its incredible generosity, in its profound humanity, there’s little I’ve seen of late that comes close. [World Premiere: International Film Festival Rotterdam]

2. Mr. Junjun (Niu Niu, China)

In a masterpiece the world is sleeping on, Niu Niu forges a simmering, Dardennes-style character study of a middle-aged taxi driver on the brink of explosion. A fifty-year-old single man responsible for a recalcitrant, semi-paralyzed father, Mr. Junjun must recover his debts to get out of a deep financial hole, but every effort he makes in this direction pushes him further towards the point of no return. The cruel pleasure the film offers is in prolonging Junjun’s moment of rupture through a series of secondary errands that he must run order just to stay afloat: the picture of life passing by even before you can get a hold on it. And yet, this is no mean neorealist melodrama. We have very little access to the inner universe of the bespectacled Junjun, who is a pure man of action, filmed from behind, moving purposefully through the world if only in order to stay where he is. You sense that this man will break down any minute, yet there is tremendous tenderness and grace in him — and in the film, for him. Prepare to be knocked down by the most sublime ending of the year. [WP: Pingyao International Film Festival]

In a masterpiece the world is sleeping on, Niu Niu forges a simmering, Dardennes-style character study of a middle-aged taxi driver on the brink of explosion. A fifty-year-old single man responsible for a recalcitrant, semi-paralyzed father, Mr. Junjun must recover his debts to get out of a deep financial hole, but every effort he makes in this direction pushes him further towards the point of no return. The cruel pleasure the film offers is in prolonging Junjun’s moment of rupture through a series of secondary errands that he must run order just to stay afloat: the picture of life passing by even before you can get a hold on it. And yet, this is no mean neorealist melodrama. We have very little access to the inner universe of the bespectacled Junjun, who is a pure man of action, filmed from behind, moving purposefully through the world if only in order to stay where he is. You sense that this man will break down any minute, yet there is tremendous tenderness and grace in him — and in the film, for him. Prepare to be knocked down by the most sublime ending of the year. [WP: Pingyao International Film Festival]

3. Slow Shift (Shambhavi Kaul, India-USA)

The work of Shambhavi Kaul, which has a knack for transforming real landscapes into otherworldly vistas, finds its perfect subject in the medieval city of Hampi in Southern India. The seat of the Vijayanagara Empire in the fourteenth century, Hampi is today a World Heritage Site attracting tourists from across the globe. In Slow Shift, Kaul crafts a spectral, non-narrative travelogue of the site that unearths its historical, mythical, geological, ecological and cultural layers. Weaving together images of stately rock-cut monuments, precariously posed stone clusters and an army of langurs taking over the depopulated site, the film forges a post-human space eerily resonant with the barren cityscapes that became common during the pandemic years. In a manner reminiscent of Richard Serra’s monumental steel sculptures, Slow Shift strikes a precarious balance between majestic stasis and imminent collapse. By combining moments of instantaneous change in the landscape with more long-term transformations as evidenced by Hampi’s weatherworn structures, the film evokes the different time scales simultaneously at work in nature, reminding us that even the mightiest empire will turn to rubble one day. It’s truly a planet of the apes, and we’re only squatters. [WP: Toronto International Film Festival]

The work of Shambhavi Kaul, which has a knack for transforming real landscapes into otherworldly vistas, finds its perfect subject in the medieval city of Hampi in Southern India. The seat of the Vijayanagara Empire in the fourteenth century, Hampi is today a World Heritage Site attracting tourists from across the globe. In Slow Shift, Kaul crafts a spectral, non-narrative travelogue of the site that unearths its historical, mythical, geological, ecological and cultural layers. Weaving together images of stately rock-cut monuments, precariously posed stone clusters and an army of langurs taking over the depopulated site, the film forges a post-human space eerily resonant with the barren cityscapes that became common during the pandemic years. In a manner reminiscent of Richard Serra’s monumental steel sculptures, Slow Shift strikes a precarious balance between majestic stasis and imminent collapse. By combining moments of instantaneous change in the landscape with more long-term transformations as evidenced by Hampi’s weatherworn structures, the film evokes the different time scales simultaneously at work in nature, reminding us that even the mightiest empire will turn to rubble one day. It’s truly a planet of the apes, and we’re only squatters. [WP: Toronto International Film Festival]

4. Fauna (Pau Faus, Spain)

Aging shepherd Valeriano lives with his herd on the outskirts of Barcelona. With his children away and with a debilitating orthopaedic problem that requires him to hang his boots, he struggles to keep his profession alive. He supplies sheep to a high-tech laboratory next door, which runs tests on them as part of its research to develop a vaccine for the Covid19 virus. Except for animals brought in through carefully controlled doorways, the lab is hermetically sealed from all biological intrusions, while Valeriano makes periodic visits to the city hospital for his therapy. From this incredibly rich scenario, Pau Faus’ Fauna weaves an extraordinary, complex examination of the ways in which science, ecology and tradition prove inextricably linked in contemporary life. “I believe that truth has only one face: that of a violent contradiction,” these words from Georges Bataille form the epigraph to Faus’ deeply moving, frequently heartrending observational documentary. With equanimity and wit, the film shines a light on humankind’s curious tendency to accelerate change while also fighting it, to master nature and technology while also being overwhelmed by them. Fauna creates ample space for reflection and critique, but supplies no easy answers. [WP: Visions du Réel, Nyon]

Aging shepherd Valeriano lives with his herd on the outskirts of Barcelona. With his children away and with a debilitating orthopaedic problem that requires him to hang his boots, he struggles to keep his profession alive. He supplies sheep to a high-tech laboratory next door, which runs tests on them as part of its research to develop a vaccine for the Covid19 virus. Except for animals brought in through carefully controlled doorways, the lab is hermetically sealed from all biological intrusions, while Valeriano makes periodic visits to the city hospital for his therapy. From this incredibly rich scenario, Pau Faus’ Fauna weaves an extraordinary, complex examination of the ways in which science, ecology and tradition prove inextricably linked in contemporary life. “I believe that truth has only one face: that of a violent contradiction,” these words from Georges Bataille form the epigraph to Faus’ deeply moving, frequently heartrending observational documentary. With equanimity and wit, the film shines a light on humankind’s curious tendency to accelerate change while also fighting it, to master nature and technology while also being overwhelmed by them. Fauna creates ample space for reflection and critique, but supplies no easy answers. [WP: Visions du Réel, Nyon]

5. The Film You Are About to See (Maxime Martinot, France)

Maxime Martinot’s short essay is a brilliant investigation into the ways in which cinema exhibition and spectatorship are mediated by paratexts within and outside the films. Repurposing a range of verbal material intended to set context for viewing — disclaimers, introductory warnings, fourth-wall breaking intertitles, notices from theatre management — the film examines the fraught, slippery nature of the relationship between text and image in cinema. Systematically interspersed with these title cards are excerpts from across the history of moving images, arranged more or less in chronology. The Film You Are About to See cogently demonstrates the extent to which such title cards serve to fix the meaning and affect of images, and to counter, as Roland Barthes put it, “the terror of uncertain signs.” The disclaimers we see in the film have a striking resemblance to modern-day trigger warnings that seek to shield viewers from presumed psychic assaults. However, in its savvy assembly of ambiguous movie clips, Martinot’s film suggests that this is an ultimately futile enterprise, for images will always find a way to escape domestication and remain polysemous in the face of texts that seek to pin them down. [WP: Cinéma du Réel, Paris]

Maxime Martinot’s short essay is a brilliant investigation into the ways in which cinema exhibition and spectatorship are mediated by paratexts within and outside the films. Repurposing a range of verbal material intended to set context for viewing — disclaimers, introductory warnings, fourth-wall breaking intertitles, notices from theatre management — the film examines the fraught, slippery nature of the relationship between text and image in cinema. Systematically interspersed with these title cards are excerpts from across the history of moving images, arranged more or less in chronology. The Film You Are About to See cogently demonstrates the extent to which such title cards serve to fix the meaning and affect of images, and to counter, as Roland Barthes put it, “the terror of uncertain signs.” The disclaimers we see in the film have a striking resemblance to modern-day trigger warnings that seek to shield viewers from presumed psychic assaults. However, in its savvy assembly of ambiguous movie clips, Martinot’s film suggests that this is an ultimately futile enterprise, for images will always find a way to escape domestication and remain polysemous in the face of texts that seek to pin them down. [WP: Cinéma du Réel, Paris]

6. Valli (Manoj Shinde, India)

Valli is a man forced to be a Jogta, a living deity with a female form, believed to be capable of blessing those who worship and honour her. When he isn’t in his Jogta form, though, Valli is bullied by the village men for his feminine ways. The premise prepares you for an overwrought, sentimentalist work, yet Valli is anything but. Manoj Shinde’s stellar film is less about an individual trapped in a body than about a body trapped in a role, deified and debased, outcast and central to the social fabric at once. Valli takes an ultra-melodramatic subject and drains it off all excess, at times with the grace and wisdom of Hou-hsiao Hsien. The lead character is subjected to abuse and insult, but what we see as his reaction is defiance, contempt, indifference, anger, humour — everything that assures us that his dignity and integrity can’t be taken away. Vast passages of non-dramatic action allow the individual to just be. Delivering what is for me the screen performance of the year, Deva Gadekar is phenomenal as Valli, infusing every frame he is in with astounding bits of non-narrative magic, his androgynous body and its gratuitous gestures becoming transfixing without being fetishized. [WP: Singapore International Film Festival]

Valli is a man forced to be a Jogta, a living deity with a female form, believed to be capable of blessing those who worship and honour her. When he isn’t in his Jogta form, though, Valli is bullied by the village men for his feminine ways. The premise prepares you for an overwrought, sentimentalist work, yet Valli is anything but. Manoj Shinde’s stellar film is less about an individual trapped in a body than about a body trapped in a role, deified and debased, outcast and central to the social fabric at once. Valli takes an ultra-melodramatic subject and drains it off all excess, at times with the grace and wisdom of Hou-hsiao Hsien. The lead character is subjected to abuse and insult, but what we see as his reaction is defiance, contempt, indifference, anger, humour — everything that assures us that his dignity and integrity can’t be taken away. Vast passages of non-dramatic action allow the individual to just be. Delivering what is for me the screen performance of the year, Deva Gadekar is phenomenal as Valli, infusing every frame he is in with astounding bits of non-narrative magic, his androgynous body and its gratuitous gestures becoming transfixing without being fetishized. [WP: Singapore International Film Festival]

7. Camping du Lac (Éléonore Saintagnan, Belgium-France)

“I’d like to tell you an odd thing that happened.” So begins Éléonore Saintagnan’s gentle shape-shifting epic that metamorphoses from an understated fable to an absorbing myth to an startlingly immediate ecological parable. There will be no shortage of odd things in this one-of-a-kind film that revels in the power of invention and storytelling. Éléonore, played by the director herself, is stranded in Brittany, France, after her car breaks down on the way to the ocean. With little choice, she decides to lodge at a camping site by the Lake Guerlédan while her car is repaired. As she observes a host of characters at the camp, the film itself embarks on strange and beautiful narrative excursions. Together, these quaint detours, whose significance remains tantalizingly elusive, impart a starkly spiritual dimension to Saintagnan’s film, a sense of wonder at the various realities around us, visible and invisible. A gorgeously shot exploration of isolation and community, Camping du Lac may ultimately be about the ways we are (or fail to be) in communion with the mysteries of the world, and in that regard, this is a work wholly in tune with our times. [WP: Locarno International Film Festival]

“I’d like to tell you an odd thing that happened.” So begins Éléonore Saintagnan’s gentle shape-shifting epic that metamorphoses from an understated fable to an absorbing myth to an startlingly immediate ecological parable. There will be no shortage of odd things in this one-of-a-kind film that revels in the power of invention and storytelling. Éléonore, played by the director herself, is stranded in Brittany, France, after her car breaks down on the way to the ocean. With little choice, she decides to lodge at a camping site by the Lake Guerlédan while her car is repaired. As she observes a host of characters at the camp, the film itself embarks on strange and beautiful narrative excursions. Together, these quaint detours, whose significance remains tantalizingly elusive, impart a starkly spiritual dimension to Saintagnan’s film, a sense of wonder at the various realities around us, visible and invisible. A gorgeously shot exploration of isolation and community, Camping du Lac may ultimately be about the ways we are (or fail to be) in communion with the mysteries of the world, and in that regard, this is a work wholly in tune with our times. [WP: Locarno International Film Festival]

8. Mithya (Sumanth Bhat, India)

After the sudden death of their parents, eleven-year-old Mithya and his young sister are taken by their aunt and uncle to their home in Udupi, much to the exasperation of the boy’s paternal relatives back in Mumbai. While the two clans fight for custody, Mithya struggles to find his moorings in a new environment, his growing sense of security undermined by a creeping feeling of re-living his original tragedy. Engineer-turned-filmmaker Sumanth Bhat’s supremely assured first feature makes us intimate with the experience of its young protagonist while also keeping us at a critical remove from his thoughts. A work that trusts the audience’s capacity for imagination and empathy, Mithya equally respects the complexity of a bereaved child’s inner world, never giving into facile poetry or genre convention. The adults, too, are invested with great dignity even when they are flawed individuals; Mithya’s uncle gets possibly the most piercing line of dialogue I heard this year, one that reveals an entire childhood. With its magnificent child performances in long shots, bold sense of ellipsis, delicately sketched character motivations and unnerving editing associations, Mithya is a virtuoso work end-to-end, an exemplar of honest, personal filmmaking. [WP: MAMI Mumbai Film Festival]

After the sudden death of their parents, eleven-year-old Mithya and his young sister are taken by their aunt and uncle to their home in Udupi, much to the exasperation of the boy’s paternal relatives back in Mumbai. While the two clans fight for custody, Mithya struggles to find his moorings in a new environment, his growing sense of security undermined by a creeping feeling of re-living his original tragedy. Engineer-turned-filmmaker Sumanth Bhat’s supremely assured first feature makes us intimate with the experience of its young protagonist while also keeping us at a critical remove from his thoughts. A work that trusts the audience’s capacity for imagination and empathy, Mithya equally respects the complexity of a bereaved child’s inner world, never giving into facile poetry or genre convention. The adults, too, are invested with great dignity even when they are flawed individuals; Mithya’s uncle gets possibly the most piercing line of dialogue I heard this year, one that reveals an entire childhood. With its magnificent child performances in long shots, bold sense of ellipsis, delicately sketched character motivations and unnerving editing associations, Mithya is a virtuoso work end-to-end, an exemplar of honest, personal filmmaking. [WP: MAMI Mumbai Film Festival]

9. Dreams About Putin (Nastia Korkia & Vlad Fishez, Russia)

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the widely reported phenomenon of people dreaming about Vladmir Putin found a new life, with Russian citizens turning to social media to describe their nocturnal encounters with their dear leader. In Dreams About Putin, Nastia Korkia and Vlad Fishez put together a hypnotic anthology of such dreams, recounted by interviewees to the camera and subsequently rendered as oneiric mindscapes in a 3D video-game engine. Periodically woven between these animated passages are archival clips of the real Putin delivering a Christmas address, atop a glider or going on a hike. Are the interviewees dreaming, or are they being dreamt? A work perfectly reflective of a world of tinpot dictators, lopsided wars and generative AI, Dreams About Putin presents a stunning look into the deliriums of those in power and the powerlessness of those who can only be witnesses to it. Korkia and Fishez concoct a bleak vision of a Russia trapped in a megalomaniac’s nightmare in which even live-action footage of Putin’s macho outings acquires a thoroughly surreal quality. Simple, funny, entrancing, with an end sequence that is the most glorious dream of all. [WP: International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam]

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the widely reported phenomenon of people dreaming about Vladmir Putin found a new life, with Russian citizens turning to social media to describe their nocturnal encounters with their dear leader. In Dreams About Putin, Nastia Korkia and Vlad Fishez put together a hypnotic anthology of such dreams, recounted by interviewees to the camera and subsequently rendered as oneiric mindscapes in a 3D video-game engine. Periodically woven between these animated passages are archival clips of the real Putin delivering a Christmas address, atop a glider or going on a hike. Are the interviewees dreaming, or are they being dreamt? A work perfectly reflective of a world of tinpot dictators, lopsided wars and generative AI, Dreams About Putin presents a stunning look into the deliriums of those in power and the powerlessness of those who can only be witnesses to it. Korkia and Fishez concoct a bleak vision of a Russia trapped in a megalomaniac’s nightmare in which even live-action footage of Putin’s macho outings acquires a thoroughly surreal quality. Simple, funny, entrancing, with an end sequence that is the most glorious dream of all. [WP: International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam]

10. Berlin (Atul Sabharwal, India)

Few Indian filmmakers have a firmer command over vernacular genre filmmaking than Atul Sabharwal, who is at the top of his game in Berlin, a scintillating spy thriller revolving around sign language (!) in which we become, as one character puts it, outsiders who feel like insiders. 1993, New Delhi. The Indian Intelligence Bureau has arrested a deaf-mute man suspected of plotting the assassination of Russian president Boris Yeltsin, who is in the country to renew diplomatic ties after the fall of the Soviet Union. They recruit Pushkin, a sign-language instructor, to help them with their interrogation, but the translator is soon nudged out of his neutrality by a rival governmental organization. Berlin, named after a café that was a safe trading post for spies of all stripes, finds Pushkin, as well as India, at a moment of swaying allegiances. A masterclass in staging what is essentially an extended, talky interrogation, Sabharwal’s super-smart, giddily plotted film sweeps us into a treacherous terrain of self-preserving intelligence agencies competing for legitimacy in a new world order. Come for the spectacle of Rahul Bose chewing scenery, stay for an exquisite treatise on the slow demise of the Non-Alignment Movement. [WP: Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles]

Few Indian filmmakers have a firmer command over vernacular genre filmmaking than Atul Sabharwal, who is at the top of his game in Berlin, a scintillating spy thriller revolving around sign language (!) in which we become, as one character puts it, outsiders who feel like insiders. 1993, New Delhi. The Indian Intelligence Bureau has arrested a deaf-mute man suspected of plotting the assassination of Russian president Boris Yeltsin, who is in the country to renew diplomatic ties after the fall of the Soviet Union. They recruit Pushkin, a sign-language instructor, to help them with their interrogation, but the translator is soon nudged out of his neutrality by a rival governmental organization. Berlin, named after a café that was a safe trading post for spies of all stripes, finds Pushkin, as well as India, at a moment of swaying allegiances. A masterclass in staging what is essentially an extended, talky interrogation, Sabharwal’s super-smart, giddily plotted film sweeps us into a treacherous terrain of self-preserving intelligence agencies competing for legitimacy in a new world order. Come for the spectacle of Rahul Bose chewing scenery, stay for an exquisite treatise on the slow demise of the Non-Alignment Movement. [WP: Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles]

Special Mention: The Other Profile (Armel Hostiou, France-DRC)

Favourite Films of

2022 • 2021 • 2020 • 2019 • 2015 • 2014 • 2013 • 2012 • 2011 • 2010 • 2009

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie review – snapshots of intimacy | Autobiography and memoir

In 2021, the renowned French author Annie Ernaux published Exteriors, a random selection of journal entries written while she lived for a time in the Parisian suburb of Cergy-Pontoise. It stands apart from the books that have made her reputation as a fearless chronicler of her own life and relationships – the likes of Simple Passion (1993), Happening (2001) and A Girl’s Story (2020) – eschewing the unflinchingly intimate and semi-autobiographical approach that helped earn her the Nobel prize in literature in 2022. Instead, as its name suggests, Exteriors is detached and outward-looking. Her aim, she said, was to “describe reality as through the eyes of a photographer and to perceive the mystery and opacity of the lives I encountered”.

Despite its oddly academic-sounding title, The Use of Photography – note the singular – bears little relation to its predecessor, being a return to the intensely personal style for which Ernaux is revered. The difference here is that, although the lens is once again turned on herself, her reflections – on desire, illness, memory and encroaching mortality as well as photography – are juxtaposed with those of her former lover Marc Marie, a journalist and photographer with whom she had a prolonged and passionate love affair in 2003. Rather than dilute the intensity of her prose, their to-and-fro conversation somehow works.

The arc of their relationship is sketched in a series of 14 snapshots that are, in essence, 14 variations on a single subject: their discarded clothes and shoes lying in a tangled jumble across the floors of various apartments and hotel rooms. On first encountering these scattered remnants of the fumbled and hurried prelude to their lovemaking, Ernaux was overcome, she writes, by “a sensation of beauty and sorrow” and immediately went to find her camera lest “this arrangement born of desire and accident” would simply disappear if not recorded.

Certain elements recur throughout: her fashionable mules, his unlaced work boots; her unfurled stockings, his crumpled denim jeans. (Oddly, the photos are printed in black and white throughout, despite there being several references in the texts to the colour of clothes and objects.) Blessedly, the sexual act itself remains out-of-frame throughout, both of them no doubt aware of French philosopher Roland Barthes’s insistence that, in photography, the erotic should be “a kind of subtle beyond”, evoking desire most powerfully by what it suggests rather than what it shows.

Intriguingly, Ernaux’s initial essay is a response to a photograph that she took but has chosen not to include: a closeup snapshot of her lover’s erect penis in which the camera flash “makes a drop of sperm glisten at the tip of the glans, like a bead”. The primary reason for the absence of visual evidence, it turns out, is privacy rather than propriety – “I can describe it, but I could not expose it to the eyes of others”.

The purpose of the almost mundane images that Ernaux and Marie chose to include – their primary use as intimated in the book’s definitive title – lies to a great degree in the prose they have inspired. They are not so much aide-mémoires as melancholy traces of their once fervent but now dissipated desire, which Ernaux retrospectively interrogates in her inimitable way. At one point, Marie compares them to a diary of “love and death”, but it is through the writing about them – melancholy, insistent, self-questioning – that the darker themes of mortality and loss fully emerge.

“When we started to take these photographs, I was undergoing treatment for breast cancer,” Ernaux tells us, matter-of-factly, in her short introduction. A few pages later, in the first essay proper, her forensic eye reveals the starkly intimate details of their first night together, which, like every aspect of her life at that time, existed in the shadow of her illness. “I didn’t take off my wig in bed. I didn’t want him to see my bald head. As a result of chemotherapy, my pubis was bald too. Near my armpit was a sort of protuberant beer cap, under the skin, a catheter implanted there at the start of treatment.”

Their love affair is punctuated with visits to the Institut Curie and the book details visceral descriptions of her physical and psychological condition, her punishing treatments and her acute sense of death’s imminence. Throughout this heightened interregnum, their intense couplings become a kind of defiance of the same. Self-pity, it goes without saying, is not her style. “I had told very few people about my cancer,” she writes at one point. “I wanted no part of the kind of sympathy which could never conceal, whenever it was expressed, the obvious fact that for others I had become someone else. I could see my future absence in their eyes.”

Against these passages of insight and stark revelation, Marie somehow holds his own as a collaborator. His writing is attuned to the formal aspects of the photographs, but also their limits in terms of what they can describe or evoke. Often they awaken fragments of memory from his own childhood. “My clothes are nowhere to be seen,” he writes of one image. “It’s as if I weren’t there, as if I were absent from the world as I was from all those joyless Christmases.” It was only when I retrospectively read his single line author biography at the start of the book, in which he is referred to in the past tense, that I realised Marie is no longer with us. He died in 2022. (The book was first published in France in 2005.) Ernaux recently told an interviewer: “I was notified of his death by a letter sent to me by his cardiologist.” His absence lends another layer of melancholy to their shared remembering.

Towards the end of the book, Ernaux asks herself the impossible question: “How do I conceive of my death… my non existence?” That, in turn, precipitates a short philosophical meditation on the unimaginable. “None of what awaits us IS thinkable,” she reflects, “but that’s just the point: there’ll be no more waiting. Or memory.” It is this “shadow of nothingness”, she concludes, that informs The Use of Photography and, indeed, all her work. Without it, she asserts, “writing, even of a kind most acquiescent to the beauty of the world, doesn’t really contain anything of use to the living”.

Maciej Pestka

All images © Maciej Pestka

Brad Feuerhelm rubs shoulders with Maciej Pestka’s self-published photobook The Life of Psy and gets a glimpse into a hilarious case of mistaken identity.

Maciej Pestka’s The Life of Psy is a brilliant navigation between the borders of fame, photography, and the complexities of credence sought through images. During Barcelona Fashion Week in 2013, Korean-born, French-raised Dennis Carre attended a whole host of parties and events in which people throughout the fashion and beauty industry wrongly identified him as K-Pop singer, Psy of ‘Gangnam Dance’ fame. Quick to capitalise on the doppelganger syndrome he represented, Carre’s appearance takes on a surreal façade as he tangos and kisses his way through a bevy of fashion mavens at various parties, where his image or rather the image of an international superstar administer Carre attention to acts of debauchery and trickery.

Maciej Pestka’s photographs themselves are event-type images where the rules of composition and pictorial photographic systems are reduced to a pop-and-flash candid mimicry much en vogue in fashion circles at present. But the point is not really about the quality of the photograph itself, but that of the embrace of spectacle and fame. Clever not to present Carre’s audience as too vacuous or vain, the photographs become a totem of celebration and “I was there” type of infamy. Brilliantly paced throughout the book are shots of Carre at work, partying and living up someone else’s life. Added ephemeral documents such as ‘cease and desist’ letters from Psy’s management add further umpf to the joke and bestow added value to the book as spoof and document of the existential trauma of where belief and need reside.

‘Play It Straight’ spins traditional theater in a modern way – The Connection

‘Play It Straight’ spins traditional theater in a modern way The Connection

Source link

From Here to the Great Unknown by Lisa Marie Presley and Riley Keough review – a book built on grief | Autobiography and memoir

What to expect from Lisa Marie Presley’s memoir? Some sanitised, cagey reminiscences, dutifully studded with anecdotes about her father, Elvis, the king of rock’n’roll, who died aged 42 in 1977? Instead, it’s a warts and all jaw-dropper. The marriages (including Michael Jackson and Nicolas Cage). The drugs (Lisa Marie spiralled into opioid addiction after a caesarean section to deliver her twins). And that’s before the revelations about her son Ben Keough’s 2020 suicide (she kept his body on dry ice in her California home for two months). When her actor daughter, Riley Keough (from Daisy Jones & the Six), writes that she wants Lisa Marie to emerge from the pages of the memoir as a “three-dimensional character”, she’s not kidding.

The book is co-authored by Keough from in-depth taped interviews with her mother just before her death aged 54 in 2023 (from cardiac arrest and a small bowel obstruction caused by complications from bariatric surgery). Keough’s own words appear throughout (in a different typeface), especially frequently towards the end.

First, though, we’re transported to Presley’s childhood as the overindulged princess of the Memphis, Tennessee mansion Graceland, with a hamburger-shaped bed and a plane named after her. A daddy’s girl, even after Elvis’s divorce from her mother, Priscilla, she would ride around the grounds in her own golf cart and threaten to get staff sacked.

Elvis looms large in these passages: taking his daughter on a rollercoaster with a gun in a holster; shooting snakes in the grounds. He was a long-term prescription drug addict and Lisa Marie would sometimes find him passed out on the floor. She watched Elvis carried out of Graceland the day he died: “I saw his head, I saw his body, I saw his pyjamas, and I saw his socks at the bottom of the gurney.” She was nine years old.

What would that do to a child? In subsequent years, she responded with the standard teenage cocktail of cynicism and rebellion: any drugs, bar heroin (“anything I could swallow, snort, eat, sniff”); terrible boyfriends, one of whom orchestrated a paparazzi set-up. She had howling insecurities as the daughter of the “king”. When Presley eventually made music, she resisted pressure to sound like her father.

Nor did she feel close to her mother. Elvis met Priscilla when she was 14 (“it was a different time”, writes Lisa Marie, brusquely noting they didn’t have sex until her mother was 18). Priscilla springs from these pages like some southern belle ice queen. After Elvis’s death: “It was a one-two punch: he’s dead and I’m stuck with her.” When they both became Scientologists, Lisa Marie felt Priscilla was “dumping” her there. Later there was a truce, but you don’t sense a real reconciliation: “People think I’m a bitch because unfortunately I have my mom’s chilly thing.”

Her healthiest relationship was with Riley and Ben’s father (Danny Keough), and they remained lifelong friends. While the Cage union is dealt with relatively swiftly and politely, the mid-90s marriage to Jackson gets the full candid treatment. She brushes aside the child molestation accusations (“I never saw a goddamn thing like that. I personally would’ve killed him if I had”). He told her he was a virgin (“He said Madonna had tried to hook up with him once, too, but nothing happened”) and was interested in her sexually (“He said: ‘I’m not waiting!’”). Later, Presley would start to doubt Jackson, who also had drug problems and his own anaesthetist. She also suspected he would dump her if she had his much-wanted children: “He was very controlling and calculating.”

There is lots more going on too, as she succumbs to opioids, drifting in and out of rehab. But it’s the passages about her son’s body that make you wonder if you’re hallucinating (“I think it would scare the living fucking piss out of anybody else to have their son there like that. But not me”) – especially when she shows a tattooist the tattoo she wants by displaying it on Ben’s dead hand.

Reading this, an uneasy thought occurs. Presley may have been happy to do the tapes, but would she have wanted it all published? We’ll never know. Certainly, it’s clear that Presley was nothing if not radically honest. It’s also striking how Keough seems to almost plead with the reader to understand and love her mother as much as she does. Ultimately, this is a book built on grief: Lisa Marie Presley’s for her father and son, but also a daughter’s for her mother.

Who Has Been Voted Off Strictly Come Dancing in Week 4 ?

Nick Knowles is the third celebrity to depart the dancefloor in Strictly Come Dancing 2024

Nick and Luba have left the Strictly Come Dancing competition following a dance off against Shayne and Nancy during the third Results Show of the series.

Both couples performed their routines again; Shayne and Nancy performed their Cha Cha to Ain’t No Love (Ain’t No Use) by Sub Sub feat. Melanie Williams. Then, Nick and Luba performed their Charleston to Rain on the Roof from the film Paddington 2.

After both couples had danced for a second time, the judges delivered their verdicts:

- Craig Revel Horwood chose to save Shayne and Nancy.

- Motsi Mabuse chose to save Shayne and Nancy.

- Anton Du Beke chose to save Shayne and Nancy.

With three votes in favour of Shayne and Nancy, they won the majority vote meaning that Nick and Luba would be leaving the competition. Head Judge Shirley Ballas also agreed and said she would have decided to save Shayne and Nancy.

When asked by Tess about their time on the show, Nick said: “I’ve really, really been surprised by how much I’ve loved doing it and by two things that happen. One is how much you care each week, and the other is how much you don’t want to let down your partner. The only reason I could do this is simply because of Luba’s changes, she’s been amazing.”

Luba said: “I’ve never met someone as determined as you, and I remember you saying that if you do your best, you’ll be very happy. I think you did more than your best. Thank you.”

When asked by Tess about his partner Luba, Nick said: “Luba’s been amazing and just been so fabulous every day. And I should say thank you also to all the background staff, the physios, all the people that have actually got me through this week, and to all of my fellow competitors who have been absolutely astounding, beautiful people. There are some amazing dancers up there, and I will love watching the rest of the series.”

Sunday’s Results Show also featured a special routine from our fabulous professional dancers to Taylor Swift’s Wildest Dreams, choreographed by Mandy Moore and starring Nikita Kuzmin and Karen Hauer as the leads. Plus a show stopping musical performance of Everything’s Here and Nothing’s Lost from Snow Patrol.

The remaining 12 couples will take to the dancefloor next week when Strictly Come Dancing returns on Saturday 19 October at 1825 with the results show on Sunday 20 October at 1920 on BBC One. Both of this weekend’s episodes are available to watch now via BBC iPlayer.

Nick and Luba will be joining Fleur East and Janette Manrara for their first exclusive televised interview live on Strictly: It Takes Two on Monday 14 October at 1830 on BBC Two and BBC iPlayer.

For all the Strictly Come Dancing news, click the image below

The Met Tackles Paul Rudolph in Rare Architecture Exhibition – Architectural Record

The Met Tackles Paul Rudolph in Rare Architecture Exhibition Architectural Record

Source link

Top Of The World

I recently came back from a trip to Vancouver, and while there, I took a few day trips up in the mountains. If you’ve never been, I suggest you go. The views are spectacular.

.

6 Legal Must-Dos for Artists with Kiffanie Stahle – How to Sell Art Online

Welcome to season five, episode 26 of The Abundant Artist, the show that dispels the myth of “the starving artist” and shares how you can live an abundant life as an artist and make a living from your talent, one interview at a time.

Joining Cory in today’s podcast is Kiffanie Stahle, the “friendly” lawyer who helps artists get the legal side of their art businesses in order. A firm believer in focusing on the “why” rather than the “what”, Kiffanie advises artists to first decide what they actually need to meet their business goals, rather than just investing big in legal matters that may not be required at all in their specific circumstances.

“I have always felt responsible for saying that if we’re going to spend a thousand dollars on the trademark, it needs to be worth it. It needs to move our businesses forward.” — Kiffanie Stahle

In this episode, Kiffanie spells out the six basic rules that every professional artist must adhere to, to avoid getting caught in the legal net. She mentions some free templates available on her website that may be a good starting point for artists just beginning their art career. Kiffanie also talks about how easy it could be to gather tax and other legal information in your state – often just a phone call away.

Tune in to today’s episode for more legal insights, a bit about Kiffanie’s minimalist life traveling the western US since 2020, and her goal to make life easier for small creative businesses. Well, legally at least.

In this episode:

[1:12] Cory asks Kiffanie to tell the TAA audience a little about how she started her journey as a lawyer helping artists with legal dos and don’ts.

[3:00] Kiffanie reminisces about how she founded the artist’s J.D. as a place to provide legal tools and resources for artists, and how it has now evolved into a membership community, offering books, courses and templates.

[4:38] How the year 2020 made a big life change for Kiffanie, and how her minimalist lifestyle impacted her legal thoughts.

[6:39] Is getting a trademark necessary?

[7:00] Kiffanie believes that there are only six things that are required of artists when it comes to the legal side of their small creative businesses.

[9:49] Kiffanie explains how a simple email can also be a valid contract in the eyes of the law.

[11:39] Cory asks Kiffanie how Entrepreneur Magazine has a trademark, given that a business name that merely describes what you do is not eligible for a trademark.

[16:15] When do you need to do more legal stuff, if you have covered the six necessary tasks already?

[17:54] Kiffanie has a free template on her website which artists can use to create a really simple, easy and readable privacy policy and terms of service.

[20:04] Cory asks Kiffanie to quickly define GDPR and CCPA.

[22:02] If your creative stuff is primarily targeted at children, there’s a whole lot of separate laws that you will need to be cognisant of.

[23:25] Cory asks Kiffanie to explain what one needs to do to comply with the various tax requirements.

[24:18] Kiffanie often recommends her clients to get in touch with their respective Chambers of Commerce for understanding the tax rules and regulations applicable to them.

[31:39] At what point should artists start reviewing their tax affairs on a regular basis?

[33:30] Who are enrolled agents, and how are they different from CPAs?

[35:35] To decide what legal tasks you must complete, you must know where your business is going.

[37:29] Kiffanie has been out of social media for three years now – this is one of her experiments in life minimalism.

[38:22] Cory asks Kiffanie how artists would get in touch with her if they are curious to learn more about legal matters or need legal help.

[40:06] What is Kiffanie’s takeaway from spending so much time working with creative people?

[42:08] Cory thanks Kiffanie for a super-informative episode!

Resources mentioned:

the artist’s J.D.

Stahle Law website

Kiffanie’s Website Policy Mad Libs

Kiffanie’s Legal Roadmap book

Kiffanie’s Join me for coffee each Friday

About the guest:

Kiffanie Stahle AKA Kiff is the friendly legal eagle behind the artist’s J.D. A place designed to add ease to the legalese of running your art business. She’s a firm believer that you can protect your ass(ets) without legal confusion. When she’s not geeking out on the law, you can find her and her pup Ozzy puttering around the western United States in their travel trailer. And spending lots of time sitting on her “porch”, hiking, mountain biking, birdwatching, knitting, working on her National Park cross stitch collection or badly singing while playing the ukulele around the campfire.

Kiffanie Stahle AKA Kiff is the friendly legal eagle behind the artist’s J.D. A place designed to add ease to the legalese of running your art business. She’s a firm believer that you can protect your ass(ets) without legal confusion. When she’s not geeking out on the law, you can find her and her pup Ozzy puttering around the western United States in their travel trailer. And spending lots of time sitting on her “porch”, hiking, mountain biking, birdwatching, knitting, working on her National Park cross stitch collection or badly singing while playing the ukulele around the campfire.

The Georgian Graffiti Artist Painting Through The Pandemic

Georgia started seeing its first cases of coronavirus at the beginning of March. The country announced a monthlong state of emergency on March 21 to prevent the spread of the virus and is considering an extension.

The numbers of sick people are not high yet but it is expected to get worse. The Georgian government has locked down four main cities to control the spread of the coronavirus: Tbilisi