The Georgian Graffiti Artist Painting Through The Pandemic

Georgia started seeing its first cases of coronavirus at the beginning of March. The country announced a monthlong state of emergency on March 21 to prevent the spread of the virus and is considering an extension.

The numbers of sick people are not high yet but it is expected to get worse. The Georgian government has locked down four main cities to control the spread of the coronavirus: Tbilisi

The Dark, Eerie, and Beautiful Creations of Adam Riches

When I think about Adam Riches, I think about nightmares, the shadows, faces obscured and darkness revealed. These are all things Riches evokes, often through the use of nothing but a ballpoint pen on paper. Capable of great detail, Adam Riches has amassed a social media following that stretches into the hundreds of thousands. People flock to see the darkness as only Riches can reveal it to be.

Signature to Adam Riches’ style and the darkness he conveys is the simplicity with which he’s able to produce it, a process you can occasionally see first hand in videos posted to his Instagram. In these you are treated to the movements of Riches’ choice of color for his signature ballpoint pen as he seemingly scribbles out looseshapes of discordant lines. From there he builds within that loose structure with more dense shading, crafting an eerie face drawn directly from the surreal discordant shadows which preceded it. Riches shows impressive versatility in his ability to create shape from the shade with varying levels of detail as some of his figures retain the more scribbled quality of their origin, looking like vacant skulls with darkened features. Others are more detailed, taking on the shadow of a man with hair and lips that appears to be looking at you from the under world. It’s easy to imagine Riches has seen the river Styx itself. Whether you’re a lover of art and the power of simple techniques or are just drawn to the darker side of life, Adam Riches is your artist.

Protected Area

Awards:

Best in Show

Brunswick Art Works “ArtWorks ’14” Exhibition

Ohio Watercolor Society / Jack Richeson & Co., Inc. Award

The Ohio Watercolor Society Annual Exhibition 2013

Women, Oscars, and power (a repost)

Kathleen Kennedy on the 1 January 2013 cover.

Kristin here:

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1000+ entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed. The run-up to the Oscars seemed a good time to revisit this one.

Ever since the Oscar nominations were announced on Tuesday, January 23, social media and mainstream news outlets have been full of posts and articles about the “snubs” of female directors, notably Greta Gerwig and Celine Song. Even Hilary Clinton weighed in with some Barbie-love. Of course the failure to nominate many other people, male and female, also insired similar indignant tirades by fans. How could Alexander Payne be left out when virtually everyone who sees The Holdovers adores it? What about Leonardo DiCaprio? Or Greta Lee? Or fill in the blank?

This sort of kvetching goes on every year, when inevitably a large number of worthies fail to be nominated. This year was perhaps bound to produce more of these also-rans, since as many have pointed out, this year saw an unusual number of excellent films. Christopher Nolan, Wes Anderson, and Alexander Payne released films that are arguably among their best. Aki Kaurismäki, after a gap of six years, returned with the quietly excellent Fallen Leaves. Hayao Miyazaki came out of retirement with The Boy and the Heron. Outside the Oscar nominees, major veteran filmmakers contributed Close Your Eyes (Víctor Erice) and R.M.N. (Cristian Mungui). The list could go on.

Returning to the issue of female directors and actors being snubbed by Academy voters, a few people point out that Margot Robbie is nominated for “Best Picture,” having been one of the producers of Barbie. Emma Stone is in the same position with Poor Things (though she, of course, did get nominated for Best Actress). On the whole, however, being a woman nominated for producing a Best Picture gets little or no attention, even if it is arguably as prestigious, if not more so.

This strange imbalance has gone on for a long time. On October 23, 2017, I posted a blog entry on the topic. It was inspired by a Variety cover story on Kathleen Kennedy (above). I discussed the reasons why female producers are ignored by the public and by journalists. As I say below, that happens partly because there is no “best producer” category, and in the past, the names of the producers who would claim the statuette if their films won, were not listed. I see that this year, the Academy’s website does list all the names of the producers of the Best Picture nominees. Did they read my post? I’ll never know. I note that the suggestion made in my final paragraph has not been followed by the press.

The old post does give a rundown of female producers who were nominated and in some cases won, from the first in 1973 up to 2016, by which point women were commonly being nominated in this category. For 2023, eight of the 30 producers of Best Picture nominees are women.

The original entry

We are now well into the season when award speculation begins. Well, actually Oscar speculation knows no season these days, but it snowballs between now and the announcement of the winners on March 4–at which point the speculation concerning the 2018 Oscar race revs up.

Among the issues that will inevitably come up is the question of whether more women directors will get nominated, especially following the critical and box-office success of Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman. It would be great to see more female nominees for Best Director, but the real problem is achieving more equity in the number of women being able to direct films at all. Unless more women direct more films, their odds of getting nominated will be low. Maybe the occasional Kathryn Bigelow will emerge, but overall the directors making theatrical features remain largely male.

Variety recently ran a story about initiatives to boost women’s chances in Hollywood. It stressed the low percentage of women in various key filmmaking roles:

The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University found that in 2014, women made up just 7% of the directors behind Hollywood’s top 250 films. Overall, of the 700 films the center studied in 2014, 85% had no female directors, 80% had no female writers, 33% had no female producers, 78% had no female editors and 92% had no female cinematographers.

Discouraging, except that there’s one figure that doesn’t support the lack of women. If 33% of films were without female producers, that means 67% had female producers–which is a lot better than in those other categories.

One thing that has struck me as odd is the lack of attention paid to the distinct rise in the number of female producers being up for Oscars in the recent past. This Variety article, however, is the first one I’ve seen offering numbers to show that women are doing a lot better in the producing field than in other major areas.

The missing names

Kathleen Kennedy, the lady illustrated at the top of this entry has produced seven films nominated as Best Picture, and she is considered one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. How could she not be? She produced Steven Spielberg’s films, alongside others, for many years and since October, 2012, she has been President of Lucasfilm in its incarnation as a subsidiary of Disney. She runs the Star Wars series.

In the Indie realm, producer Dede Gardner is on a roll, having since 2011 had three films nominated for the top prize in addition to wins in 2013 and 2016. Others, such as Megan Ellison and Tracey Seaward, have enjoyed multiple nominations. (I’m using the film’s year of release rather than the year when the award was bestowed.) As we’ll see, female producers are beginning to catch up to their male colleagues in number as well as prestige. Why no fuss about such important strides?

I think the main reason is that there’s no “Best Producer” category. If there were, I suspect our image of women in the industry would be very different. But there’s just a Best Picture one. In most cases neither the industry journals nor the infotainment coverage lists the producers alongside the titles of the Best Picture nominees. So who’s to know that the “Best Picture” race also is, faut de mieux, the “Best Producer” contest.

Another, perhaps less important reason why producers draw less attention is that because a film often has several producers. It’s more complicated to assign responsibility for who did what. Most people have a general idea of what directors do. They’re on set, they make decisions, and they supervise other artists. A female producer, like a male one, may have been included for many reasons. She might have done most of the work in assembling the main cast or crew members or she might have concentrated on gaining financial support. She might instead be termed a producer as a reward for crucial support at one juncture. We can’t know, and that perhaps makes it difficult for the public to get enthusiastic about producers. Of course, if journalists covered them more in the entertainment press, the public might gain more of a sense of what producers do.

Yet whatever their contribution, those producers played some sort of crucial role, and they are the ones who get up and receive the statuettes when that last climactic announcement of the evening is made. (Lately there has been a trend for the every member of the cast and crew and all their relatives present to rush onto the stage for a grand finale, but it’s the producers who give the thank-you speeches.) They can take those statuettes, with their names engraved on them, home and put them on their mantels or to their office to display in a glass case. Yet few have any name recognition outside the industry, the entertainment press, and a few academics.

Despite these producers’ importance, it’s difficult to find out who they have been over the years. Go to almost any website, including the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ own, in search of Oscar nominees stretching back through the years, and you will usually find names listed in all the other categories–but only the title of the nominated films in the Best Picture category. I finally found a complete list of Best Picture nominees’ producers compiled by an industrious contributor to Wikipedia. Going through and doing some counting and cross-checking, I have created and annotated my own list. With it I’ve tried to show the fairly steady progress that women have made in this category. I call them “nominees” below. Somewhat paradoxically, they win the Oscars, though technically the film is the official nominee.

To keep this list from becoming even longer, I’ve listed only nominated films which had one or more women among their group of producers. Up to 2008 there were five films each year. Starting in 2009 the number could be anywhere between five and ten, though it’s usually eight or nine. I give the number of nominated films starting in 2009. Assume any films not listed were produced by men. If you’re curious about who those men were, click on the link in the previous paragraph.

Here’s how things developed, including only years when female producers were “nominated.” (My comments in red.) Be patient. It gets off to a slow start, but things pick up.

And the nominees are …

1973 The Sting (WINNER) Tony Bill, Michael Phillips, and Julia Phillips.

Julia Phillips becomes the first female producer nominated since the Oscars began in 1927 and the first to win.

1982 E.T. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

The second female producer nominated.

1984 Places in the Heart. Arlene Donovon.

The third nominated female producer.

1987 Fatal Attraction. Stanley R. Jaffe and Sherry Lansing.

The fourth nominated female producer.

1989 Driving Miss Daisy. (WINNER) Richard D. Zanuck and Lili Fini Zanuck.

Lili Fini Zanuck is the second female producer to win.

1991 The Prince of Tides. Barbra Streisand and Andrew S. Karsch.

1994 Forrest Gump. (WINNER) Wendy Finerman, Steve Tisch, and Steve Starkey.

The Shawshank Redemption. Niki Marvin.

Wendy Finerman (right) becomes the third woman producer to win a Best Picture Oscar.

This is the first year when two women are nominated. From this point to the present, there has been no year without at least one female producer nominated.

1995 Sense and Sensibility. Lindsay Doran.

1996 Shine. Jane Scott.

1997 As Good as It Gets. James L. Brooks, Bridget Johnson, and Kristi Zea.

The first year when four women are nominated.

The first time two women are nominated for the same film.

1998 Shakespeare in Love. (WINNER) David Parfitt, Donna Gigliotti, Harvey Weinstein, Edward Swick, and Marc Norman.

Elizabeth. Alison Owen, Eric Fellner, and Tim Bevan.

Life Is Beautiful. Elda Ferri and Gianluigi Brasch.

Gigliotti is the fourth woman to win a producing Oscar.

1999 The Sixth Sense. Frank Marshall, Kathleen Kennedy, and Barry Mendel.

First year when a woman producer, Kennedy, is nominated for a second time.

2000 Chocolat. David Brown, Kit Golden, and Leslie Holleran.

Erin Brockovich. Danny DeVito, Michael Shamberg, and Stacey Sher.

For the second time, two women are nominated for the same film.

2001 The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2002 The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2003 The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. (WINNER) Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

Lost in Translation. Ross Katz and Sofia Coppola.

Mystic River. Robert Lorenz, Judie G. Hoyt, and Clint Eastwood.

Seabiscuit. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Gary Ross.

Walsh is the fifth woman to win in this category.

Walsh and Kennedy tie for the first woman nominated three times.

The second year when four women are nominated.

2004 Finding Neverland. Richard N. Gladstein and Nellie Bellflower.

2005 Crash. (WINNER) Paul Haggis and Cathy Schulman.

Brokeback Mountain. Diana Ossance and James Schamus.

Capote. Caroline Baron, William Vince, and Michael Ohoven.

Munich. Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy, and Michael Mendel.

Cathy Schulman is the sixth woman to win.

The third time four women are nominated.

Kennedy becomes the first woman nominated four times.

2006 The Queen. Andy Harris, Christine Langan, and Tracey Seaward.

2007 Michael Clayton. Jennifer Fox and Sydney Pollack.

Juno. Lianne Halfon, Mason Novack, and Russell Smith.

There Will Be Blood. Paul Thomas Anderson, Daniel Lopi, and JoAnne Sellar.

The first year in which five women are nominated in this category.

2008 The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Céan Chaffin.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

First time a woman, Kennedy, reaches a fifth nomination.

The third time two women are nominated for the same film.

2009 The first year of up to ten nominations. Ten films nominated.

The Hurt Locker. (WINNER) Kathryn Bigelow, Mark Boal, Nicholas Chartier, and Greg Shapiro.

District 9. Peter Jackson and Carolynne Cunningham.

An Education. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

Precious. Lee Daniels, Sarah Siegel-Magness, and Gary Magness.

Kathryn Bigelow becomes the seventh woman to win in this category. (Right, with her producing and directing Oscars.)

The fourth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2010 Ten films nominated.

Inception. Christopher Noland and Emma Thomas.

The Kids Are All Right. Gary Gilbert, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, and Celine Rattray.

The Social Network. Pana Brunetti, Céan Chaffin, Michael De Luca, and Scott Rudin.

Toy Story 3. Darla K. Anderson.

Winter’s Bone. Alex Madigan and Ann Rossellini.

The second year five women are nominated in this category.

2011 Nine films nominated.

Midnight in Paris. Letty Aronson and Stephen Tenebaum.

Moneyball. Michael De Luca, Rachael Horovitz, and Brad Pitt.

The Tree of Life. Sarah Green, Bill Pohlad, Dede Gardner, and Grant Hill.

War Horse. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Kennedy receives her sixth nomination.

The third year in which five women are nominated in this category.

The fifth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2012 Nine films nominated.

Amour. Margaret Mengoz, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, and Michael Katz.

Django Unchained. Stacey Sher, Reginald Hudlin, and Pilar Savone.

Les Misérables. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Debra Hayward, and Cameron Mackintosh.

Lincoln. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Silver Linings Playbook. Donna Gigliotti, Bruce Cohen, and Jonathan Gordon.

Zero Dark Thirty. Mark Boal, Kathryn Bigelow, and Megan Ellison.

Eight female producers nominated, besting the previous record by three.

The first year in which each of two nominated films has two female producers.

Kennedy receives her seventh nomination.

2013 Nine films nominated.

12 Years a Slave. (WINNER) Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Klein, Steve McQueen, and Anthony Katugas.

American Hustle. Charles Roven, Richard Suckle, Megan Ellison, and Jonathan Gordan.

Dallas Buyers Club. Robbie Brennert and Rachel Winter.

Her. Megan Ellison, Spike Jonze, and Vincent Landay.

Philomena. Gabrielle Tana, Steve Coogan, and Tracey Seaward.

The Wolf of Wall Street. Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, Joey McFarland, and Emma Tillinger Koskoff.

Dede Gardner becomes the eighth woman to win an Oscar in this category.

Megan Ellison becomes the first woman nominated for two films in the same year.

2014 Eight films nominated.

Boyhood. Richard Linklater and Cathleen Sutherland.

The Imitation Game. Nora Grossman, Ido Wostrowskya, and Teddy Scharzman.

Selma. Christian Colson, Oprah Winfrey, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

The Theory of Everything. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Lisa Bruce, and Anthony McCarten.

Whiplash. Jason Blum, Helen Estabrook, and David Lancaster.

2015 Eight films nominated.

Spotlight. (WINNER) Blye Pagon Faust, Steve Golin, Nicole Roaklin, and Michael Sugar.

The Big Short. Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, and Brad Pitt.

Bridge of Spies. Steven Spielberg, Marc Platt, and Kristie Macosko Krieger.

Brooklyn. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

The Revenant. Arnon Milchan, Steve Golin, Alejandro G. Iñárittu, Mary Parent, and Keith Redmon.

Blye Pagon Faust and Nicole Roaklin become the ninth and tenth winners.

For the first time two women win for the same film.

For the second time, two nominated films have two female producers.

2016 Eight films nominated.

Moonlight. (WINNER) Adela Romanski, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

Hell or High Water. Carla Haaken and Julie Yorn.

Hidden Figures. Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenro Topping, Pharrell Williams, and Theodore Melfi.

Lion. Emile Sherman, Iain Canning, and Angie Fielder.

Manchester by the Sea. Matt Damon, Kimberly Steward, Chris Moore, Lauren Beck, and Kevin J. Walsh.

Adela Romanski and Dede Gardner become the eleventh and twelfth winners.

For the second time, two women win for the same film.

For the second time, eight women are nominated, which so far remains the record.

Why should these names be hidden?

So we have overall 88 nominations for women, with twelve women winning Oscars for producing films. That compares with four nominations and one win for female directors. Women have not come all that close to parity with men in the producing category, but compared to the directors category, which people seem to take as a bellwether for the status of professional women in Hollywood, it’s spectacular. Moreover, we can see a fairly steady growth over the past twenty-three years, to the point where seven or eight producing nominations a year routinely go to women.

Of course, Oscars are not the only or the most objective way of measuring women’s power in Hollywood. One could try a similar examination of the number of women producing Hollywood’s top box-office films over the years. I assume there would be a similar growth in numbers, but the measurement would probably be a little more nuanced. That would be a much bigger project than would fit in a blog entry–even entries as long as the ones we occasionally favor our readers with. The San Diego State University study I mentioned earlier took an approach of this sort, and I’m sure there is deeper digging to be done among the statistics revealed by such research..

Given the way the Oscars have captured the public’s and the industry’s imaginations, however, the growing number of female producers being honored is a good way to point out that things may be better than they seem when one focuses narrowly on the directors category.

After all, the prescription for putting more women in the director’s chair and behind the camera and so forth is always that more female producers and writers are needed, making films for women and by women. This seems reasonable, and yet the question remains, if women are doing so well, relatively speaking, in rising to the top as producers, why, over the twenty-three years since 1994 haven’t they hired more women at every level for their film crews? (Of course, some of them have acted as producer-directors on their own projects.) Why hasn’t Kennedy, who has been firing and hiring male directors for Star Wars projects lately, ever given a female director a shot at it? Maybe she will at some point, as the evidence grows that women can create hits.

Perhaps most women producers are constrained by their fellow producers on projects, who are often men. They may feel pressured to reassure studio stockholders and financiers by sticking with the tried and true. And yet there do finally seem to be signs that studios are looking beyond the obvious pool of talent. Patty Jenkins, an indie filmmaker, directs Wonder Woman to unexpected success. Taika Waititi, a Maori-Jewish indie filmmaker from New Zealand, suddenly finds himself directing Thor: Ragnarok, which shows every sign of becoming a hit. With luck, the effect of the rise of female producers, as well as of more broadminded male ones, will finally have a significant impact on both gender and ethnic diversity in Hollywood filmmaking.

In closing, I would suggest to the press that it would be helpful for them in writing their endless awards coverage to list more than just the titles of the Best Picture nominees. Add the names of their producers, who are in effect nominated for Oscars. Treat them more like stars, the way you do with directors. I realize that there are often lingering disputes over which of the many producers attached to some films are actually the ones eligible to accept Oscars for them. But once such disputes are resolved, these “nominees” should be listed, and certainly after the awards are given out, they should be part of the historical record of Oscar nominees and winners. This would help both the public and the industry to get the big picture, not just the Best Picture.

[Oct. 24, 2017: My thanks to Peter Nellhaus for pointing out Julia Phillips’ win for The Sting in 1973. I have corrected the text accordingly.]

The Shawkshank Redemption (1994).

This entry was posted

on Sunday | January 28, 2024 at 11:49 am and is filed under Awards, Hollywood: The business.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

bright red steel frame outlines pritzker military archives center by jahn/ in wisconsin

jahn/’s State-of-the-Art Hub for Preserving Military History

Jahn/ has completed the Pritzker Military Archives Center, a state-of-the-art facility designed to house and expand the collections of the Pritzker Military Museum & Library. Relocated from Chicago to Somers, a village in Kenosha County, about 30 miles outside of Milwaukee, the 15,000-square-foot facility features exhibition space and below-grade archival storage, providing an immersive museum experience for Wisconsin visitors and residents alike. The center supports the organization’s mission to enhance public understanding of military history, celebrate the role of citizen-soldiers, and strengthen the connection between the armed forces and the people they protect. ‘We are proud to have been part of the collaborative team that brought our client’s vision for the Pritzker Military Archives Center to life,’ said Evan Jahn, President of Jahn. ‘From start to finish, our design has been shaped and informed by our shared commitment to the center’s mission of learning from past conflicts so we can help prevent future ones.’

the cantilevered roof frames an outdoor exhibit space | all images by ©Tom Rossiter

steel and high-performance glass wrap Pritzker Archives Center

The Pritzker Military Archives Center employs a 36-foot structural grid system where 390-foot trusses act as bearing walls, providing roof support and lateral stability. The cantilevered roof frames an outdoor exhibit space, creating an open and inviting presence that stands out in the landscape. The elevated roof and expansive interior maximize both functional efficiency and visual impact, providing optimal working conditions for staff and an inspiring environment for visitors. The structure’s design, inspired by World War II landing craft, features a bright red steel frame symbolizing courage and is clad in high-performance glass.

Inside, a partial-height glass partition allows the public to observe the work of curators and archivists, offering a rare view into the preservation of military history. Spanning 17.5 acres, the grounds of the Pritzker Military Archives Center reflect a deep commitment to environmental preservation, with less than 4% dedicated to structures. The surrounding landscape, designed by O2 Design, includes green walking and biking trails and dedicated picnic spots while ensuring the protection of nearby wetlands. Sustainability is central to the project. Rainwater is harvested for irrigation and a 50,561 kWh solar field provides electricity for the entire site. Chicago-based firm Jahn/ collaborated with consultants at Cyclone Energy Group and contractors at Pepper-Riley Construction to achieve a high-performance building that not only serves as a repository of military history but also demonstrates the close integration of architecture and engineering, which has defined Jahn through its 60-year legacy.

390-foot trusses act as bearing walls to support the roof and provide lateral stability

the building demonstrates the close integration of architecture and engineering

the exterior presents an open and inviting image to visitors, creating a striking presence in the landscape

O.P. Sharma Photography: Pioneering Indian Pictorialist’s Artistic Vision and Legacy | Retrospective Exhibition 1950s-1990s – Frontline

O.P. Sharma Photography: Pioneering Indian Pictorialist’s Artistic Vision and Legacy | Retrospective Exhibition 1950s-1990s Frontline

Source link

Story of the Week: Fleetwood Mac Sound Engineer Sues Stereophonic Playwright

(© Julieta Cervantes)

On Tuesday, attorneys representing Kenneth Caillat and Steven Stiefel filed a lawsuit in the United States Court for the Southern District of New York against playwright David Adjmi and the Broadway producers of Stereophonic, winner of this year’s Tony Award for Best Play.

The complaint alleges that Stereophonic is an “unauthorized adaptation” of Caillat’s 2012 memoir, Making Rumours: The Inside Story of the Classic Fleetwood Mac Album (which he co-wrote with Stiefel) about his time as a sound engineer (later promoted to co-producer) of one of the most popular albums in history. Caillat and Stiefel are seeking damages and a possible injunction on performances.

Story of the Week will take a deep dive into the suit and its prospects for success. But first, a quick refresher:

What is Stereophonic?

David Adjmi’s drama is about a band comprising two Americans and three Brits. It’s 1976 and they’ve settled into a Sausalito recording studio to lay down their forthcoming album, which takes over a year to record. Seated on the other side of the control panel, we witness their personal trials and professional triumphs as the band becomes increasingly famous. As far as three-hour hyper-naturalistic dramas go, it’s absolutely riveting — made even more delightful by Will Butler’s original music.

The play debuted last October at Playwrights Horizons off-Broadway and the similarities to Fleetwood Mac were immediately apparent. “Adjmi’s five-member band is made up of two couples, who are loose stand-ins for John and Christine McVie, and Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham, as well as a Mick Fleetwood-esque drummer,” TheaterMania critic David Gordon wrote in his review, which, like almost every other review of the play, was glowing.

The show transferred to Broadway’s John Golden Theatre in April 2024, opening in time to be considered for the Tony Awards — and boy was it ever. The show received 13 nominations, more than any other play in history. It went on to win five Tonys on June 16, including the all-important Best Play Award, which our team unanimously predicted.

(© Julieta Cervantes)

It was several weeks before that, in May, when critic Hannah Gold first noted the similarities between Stereophonic and Making Rumours in the New York Review of Books. She writes, “Caillat also claims that Buckingham once pressured him to record over a guitar riff in the hopes that his next take would be even better. Caillat did what he was asked. Then Buckingham decided he liked the previous take after all, but it no longer existed, so he vented his frustration at Caillat by screaming in his face — an exchange nearly identical to one in the play between Peter and Grover.” Grover is the character played by Eli Gelb in Stereophonic, whose journey from sound engineer to co-producer seems to mirror Caillat’s.

Last week, the New Yorker published an article by Michael Schulman in which Caillat attends a performance of Stereophonic — his very first Broadway show! His review? “I feel ripped off!” In retrospect, this article was a harbinger of the lawsuit to come.

What does the lawsuit claim?

The complaint calls Stereophonic a “flagrant and willful infringement of [Caillat and Stiefel’s] copyrighted work.” It lays out in detail the similarities between the book and the script, often presenting the texts back-to-back in a manner that is uncommonly theatrical (and devastating) for a lawsuit.

In addition to the above-described scene, in which Peter screams at Grover for taping over his guitar solo, the complaint cites the scene in which Holly screams at Grover, “You start paying attention to the tempo and the key and the instruments and give us a little fucking help,” comparing it to a similar line uttered by Christine McVie in Making Rumours: “We want you guys to start paying attention to tempos and keys and tuning and other important things to help us out here.”

There are others, including a scene in which Peter decides to record a bass part for Reg that parallels an anecdote in Making Rumours, in which Buckingham records a bass part for John McVie. There’s the passage about the Sausalito Houseboat Wars, which comes as an odd digression in Stereophonic, and is also a subject covered in the book. The suit also notes references to Tony Orlando and Grover’s use of the phrase “wheels up” to indicate the start of recording — the exact phrase Caillat used during the recording process of Rumours.

Cleverly, Caillat and Stiefel’s lawyers anticipate a potential defense that worked for Adjmi in a suit brought against him by the rights holder of the sitcom Three’s Company concerning his play 3C. A court found that play, a parody of the original sitcom, fell under the “fair use” doctrine, which is meant to prevent rights holders from using their copyright to stifle criticism. “The case of Stereophonic is very different because the show is not a parody or other fair use of Making Rumours,” the suit contends, “Indeed…Mr. Adjmi denies that he used Making Rumours at all, so he cannot claim fair use of the book.”

If Stereophonic had quietly played out its run at Playwrights Horizons and never transferred to Broadway, I wouldn’t be writing about this lawsuit today, because I doubt anyone would have discovered the similarities (off-Broadway is, to my eternal frustration, a passion for a very boutique audience). But again, Stereophonic is the most Tony-nominated play in Broadway history and, according to the complaint, “has grossed more than $20 million since opening on Broadway in April 2024.” Caillat and Stiefel obviously want some of that bounty, but the far bigger prize seems to be the potential future of the property.

“The Stereophonic show is harming the downstream market for adaptations of Making Rumours,” the suit contends. It notes that Adjmi has discussed a film adaptation with Deadline, and that Caillat is engaged in “ongoing efforts” to adapt his book into a movie. “A movie version of Stereophonic would not only continue to infringe on Plaintiffs’ copyright,” the complaint reads, “but also undermines the potential for Plaintiffs to make their own film.”

(© Tricia Baron)

Will we see Stereophonic in court?

It’s certainly possible, but I suspect Adjmi’s co-defendants (a group that includes Playwrights Horizons, John Johnson and Sue Wagner, Seaview, Sonia Friedman Productions, and the Shubert Organization) will see the writing on the wall and quietly seek a settlement. It’s hard to imagine a court injunction shuttering an ongoing Broadway play (as the lawsuit threatens), much less one that has been so laureled. Why slaughter the goose when there’s still so much more gold to enjoy?

Caillat and Stiefel may be satisfied with a “based on” credit and a big fat check. They might even happily consult on the film — for a fee. Because in Hollywood, we really can have “Happily Ever After.”

TheaterMania reached out to the Stereophonic team for comment but has not heard back as of publication. However, responding to the plagiarism allegations in the New Yorker article, Adjmi said, “When writing Stereophonic I drew from multiple sources — including autobiographical details from my own life — to create a deeply personal work of fiction. Any similarities to Ken Caillat’s excellent book are unintentional.”

He’s obviously read it, and “excellent” might make a lovely cover blurb for the second edition.

While similarities in storytelling and songwriting are endemic to the creative process, that kind of unintentional plagiarism is often sorted out by lawyers (poor Anton Bruckner is dead, lawyerless, and in the public domain).

In this case, it’s hard to believe so many exact similarities are the product a creative mind playing tricks on itself. But who knows? Adjmi may choose to keep singing that song.

The Long View | Gardiner’s farcical comeback shames us all

Florence Lockheart

Friday, October 11, 2024

Andrew Mellor argues that allowing the disgraced conductor to gazump his former ensembles is a damning indictment of our industry’s unwillingness to change

Don’t miss out on our dedicated coverage of the classical music world. Register today to enjoy the following benefits:

-

Unlimited access to news pages -

Free weekly email newsletter -

Free access to two subscriber-only articles per month

Parris Goebel Is Changing the Way Rihanna, SZA and Other Women Dance

In February 2023, Rihanna took the field during the Super Bowl LVII halftime show for her first performance in five years. As the opening notes of “Rude Boy” played, a group of dancers in identical puffy white suits and sunglasses clustered in the middle of the stage, moving with forceful precision as the music intensified.

As the music gathered momentum, the camera raced through the crowd of scowling dancers until, finally, Rihanna appeared. Their movement was sensual but assertive, bordering on violent, flitting between slow body rolls and athletic thrusts. It was sexy — hands stroking, chests heaving — but strange.

The choreographer behind this viral performance, 32-year-old Parris Goebel, has established herself as one of the music industry’s most innovative and in-demand artists. She has choreographed tour routines and music videos for the likes of SZA, Doja Cat, Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande.

Rihanna’s Super Bowl halftime show, 2023.

Justin Bieber, “Sorry,” 2015.

SZA, “Hit Different,” 2020.

Goebel caught Rihanna’s attention after one of her dance crews performed a routine in 2015 choreographed to the song “Bitch Better Have My Money.” The singer was amazed at how Goebel’s work reimagined her own song. “It blew my mind!” Rihanna said in an email. “Every formation came out of nowhere, the movement was incredibly sharp and in sync, the viciousness in the faces of every dancer and the way the music was reimagined … It all just took my breath away, and I hadn’t felt something like that before through dance.”

There’s a raw, instinctive quality to Goebel’s routines: The dancers look as if they aren’t just dancing but are following an elemental urge. Over the last decade, pop stars have sought out this off-kilter vision of how female bodies can move. As a result, Goebel is reshaping what pop choreography looks like — and exploding our ideas of what makes a femme body desirable.

This style is a far cry from the sexual provocation of the early 2000s. There were notable exceptions, including choreographers like Fatima Robinson and artists like Missy Elliott, who was a source of inspiration for Goebel from a young age.

But unambiguous sexuality was often equated to female empowerment in videos for songs like Britney Spears’s 2001 hit single “I’m a Slave 4 U,” Christina Aguilera’s 2002 “Dirrty” or Rihanna’s 2005 “Pon de Replay,” in which she appears loose-limbed and sinuous, wearing scant clothing.

Rihanna, “Pon de Replay,” 2005.

Christina Aguilera, “Dirrty,” 2002.

Britney Spears, “I’m a Slave 4 U,” 2001.

Tate McRae, “Greedy,” 2023.

These videos underline the idea that female power derived from sexual appeal. It’s not as if this overt display of sexuality has vanished from contemporary pop choreography. Take Tate McRae’s recent video for “Greedy,” in which McRae writhes around an ice rink.

But Goebel’s routines push past titillation into startling, even disturbing territory. At times, the moves feel like something pulled from a martial arts movie. Her choreography conveys formidable power and aggression — yet it’s still playful and lighthearted. In a routine she choreographed for Nike during Paris couture week, the dancers rolled and thrust their chests forward in a unsettling, Frankenstein-ish lurch, before leaping from the stage and strutting forward, arms crossed, like something Gene Kelly might do in “Singin’ in the Rain.”

The Nike Paris couture week performance.

“Singin’ in the Rain,” 1952.

Even movements that feel familiar (as when her dancers lay on their backs, legs scissoring open in the classic strip-club pose) are immediately transformed into something borderline animalistic. Soon after, the dancers growled at the audience as they drove their sternums to the sky. Goebel’s artistry lives in these juxtapositions — in the reshaping of something recognizably erotic into something strange and surprising.

Raised in Auckland, Goebel began choreographing at 10. Her mother is Samoan Chinese, and Goebel was exposed to many genres of dance, including traditional Polynesian and hip-hop, from a young age. Her routines won local talent competitions, and she taught her first class at 13. In 2007, she dropped out of high school. Two years later, she founded the Palace dance studio, now home to the championship-winning dance crews the Royal Family and ReQuest.

In 2011, when Goebel was 19, she got a call: Someone on Jennifer Lopez’s team had seen Goebel’s work on YouTube and was inviting her to work on a routine for Lopez’s world tour. She recalls crashing in Lopez’s guest room during rehearsals.

Goebel at Urban Dance Camp.

YouTube was instrumental in building Goebel’s career. In 2015, a dance camp where Goebel was a guest instructor posted a video of her dancing, and the clip went viral, with fans commenting on her formidable control.

Implementing this kind of exactitude across a crowd of dancers is one of Goebel’s signatures. “I love really clean work, and I love perfect lines,” she told me. “Everyone in the right space, in the right window, at the right angle.”

In a 2019 routine that Goebel choreographed for the Royal Family, dozens of dancers formed one organism, each figure a component within a larger shape.

The Royal Family performance.

The group flowed in concert, moving as if underwater, and the synchronicity of the dancers’ movements generated a heaving energy. But as their bodies shifted smoothly from side to side, the dancers’ expressions were not so sanguine: They glared at the camera as they abandoned their fluid motion for punches and stomps. There’s something cathartic about watching a group of (mostly) women snarling in lock step, an image of power and indomitability. These women might sleep with you, but they also might kill you.

“Her work is visceral, it’s ethereal, it’s intelligent and alive.” — SZA

“There are little obsessions you have as a choreographer,” Goebel says. Two of hers are subtle hand and neck movements. In this regard, she is as inspired by the dance legend Bob Fosse as she is by hip-hop choreography.

Fosse’s influence is clear in the “Wild Thoughts” segment of Rihanna’s Super Bowl performance. “I like putting one subtle movement on 50 people,” Goebel explains. “Putting a small motion on multiple people magnifies a small idea.”

“Sweet Charity,” 1969.

Rihanna’s Super Bowl halftime show, 2023.

Her performances have retained their sexiness while shedding the obvious markers of femininity. Goebel told me she sometimes incorporates traditional Polynesian elements when it makes sense, as she did in portions of the Nike performance. Her video for Justin Bieber’s “Yummy,” for example, features dancers arranged in rows while they sink into powerful pliés.

The effect is reminiscent of the siva tau, a traditional Samoan war dance that is now often performed by rugby players before a match. Goebel juxtaposes influences — Polynesian dance, hip-hop, jazz and dancehall — in dizzying ways; the resulting performance is something that feels genuinely new.

Justin Bieber, “Yummy,” 2020.

The Samoan rugby team, 2015.

This combination of influences has led Goebel toward a style that borders on avant-garde. In performances like Doja Cat’s viral 2024 Coachella sets, we see that Goebel is a master of contemporary pop aesthetics who wants to see what else is possible.

Wearing a body suit and boots draped with long, lustrous blond hair, Doja Cat began her performance of “Demons” by crawling on the stage like a spider-woman hybrid. Her backup dancers wore hair suits that hid their bodies. The suits’ blond locks exaggerated the subtlest movements. The dancers barely looked human, their swinging hair taking the place of limbs. In their Chewbacca-like costumes, the dancers didn’t look “sexy,” but as the hair moved, its silkiness was alluring.

Doja Cat performing at Coachella, 2024.

The performance epitomized how Goebel’s boundary-pushing aesthetic rethinks not just gender but the entire idea of sexiness. In her vision sensuality — an awareness of our bodies and senses — feels more important than sexuality. She takes gut feelings and makes them concrete through dance.

“Her work is visceral, it’s ethereal, it’s intelligent and alive,” SZA said in an email. “I feel it in my tummy and my chest.”

“I love really clean work, and I love perfect lines.” — Parris Goebel

Major pop stars and people who like to dance in their living rooms intuit this. Her moves have spilled over from stadium shows to professional dance studios and trickled down to amateur dance TikTok and YouTube, inspiring everything from Halloween costumes to viral dances at high school prom rallies.

The dancer and influencer Konochan.

The dancer and influencer Tray.

The dancer natalieg.

In the meantime, Goebel isn’t slowing down. In early October, she shared a photo of the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. Rihanna’s representative confirmed that Rihanna and Goebel were shooting something at the palace, though the project is still under wraps. For her part, Goebel remains humble about her success. When I asked Goebel what she wanted people to understand about her work, she was modest. ‘‘That it’s a gift, and that I’m not actually in control.’’ She paused. ‘‘It’s all a gift, and I’m just the vessel.’’

Goebel: Styling: Damien Lloyd. Hair: Akita Barrett. Makeup: Jaime Diaz.

Konochan, Tray and natalieg videos: TikTok. All other videos: YouTube.

Why build the garden bridge when we could plant trees on Blackfriars? | Architecture

When is a garden bridge not a garden bridge? When it’s a bridge garden, according to Allies and Morrison, the Southwark-based architects who have come up with a cheap and cheerful alternative to the eye-wateringly expensive, contractually dubious proposal by Thomas Heatherwick and Joanna Lumley for a floating forest across the Thames.

Rather than spending £175m on installing two gargantuan copper-nickel plant pots in the middle of the river, in a public-private business model that could burden the taxpayer for years to come, they have realised we could simply plant some trees on a bridge that already exists. But which one?

Blackfriars bridge, which lands just a few hundred metres from the Allies and Morrison office, stretches up to 40 metres wide between its stately stone piers, carrying four lanes of traffic and a generous pavement on either side. With a bit of rejigging, the pavements could be consolidated into one 14 metre-wide, tree-planted park, while leaving enough room for cars, buses and a separated cycle lane.

By contrast, proposals for the garden bridge suggest bikes would be banned. The controversial crossing, whose campaigners have already spent almost £40m of its £60m public funding before construction has even started, would also be shut at night and closed several days a year for corporate events – part of a shaky business plan that also expects bridge users to donate £2 per crossing.

Large groups will be encouraged to register their visits in advance, phone signals will be tracked in a bid to deter protesters, while a list of draconian rules will prohibit playing musical instruments, flying kites and taking part in a “gathering of any kind”.

Freed from the burden of a huge debt and the demands of corporate sponsors, the Blackfriars bridge garden could be a truly public space. Constructed by engineer Joseph Cubitt in 1869, the structure has a built-in generosity emblematic of the days of Victorian civic pride. It already incorporates charming stone seating nooks above its five bastions, which would be incorporated into the park: “riverside alcoves for a sandwich at lunchtime, a break from a jog or a place for families to gather,” as the architects put it, “a garden for morning commuters as well as the quiet moments of urban life”.

The proposal is the latest, and perhaps the most feasible, in a series of alternatives to the costly vanity project, which was championed by Boris Johnson and remains supported by London’s new mayor Sadiq Khan, whose odd defence is that cancelling the scheme would cost twice as much as completing it.

It follows the satirical Folly for London competition, whose winner proposed constructing an eternal bonfire on the Thames. Fuelled by trees felled from London’s parks, usefully freeing up land for private development, it would be “an eternal flame dedicated to 21st-century planning departments and developers”.

Other entries to the contest included a “Scrotopolis” of bulging pink scrota and the Jesus bridge, an invisible crossing that would allow commuters to walk on water – a dream as probable as the idea that Heatherwick’s scheme could ever get this far.

The Paris Review – Control Is Controlled by Its Need to Control: My Basic Electronics Course

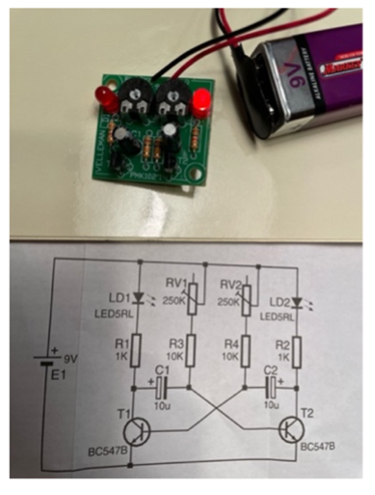

Photograph by J. D. Daniels.

Let me begin by insisting that I learned nothing.

What is left of it now, my electronics project, other than the names of these things? A solderless breadboard, and another one, and another one. A fifty-foot roll of twenty-seven-gauge insulated copper wire. Tactile switch micro assortment momentary tact assortment kit, not clear to me what that means. All these jumper wires with their connector pins, I tend to blank on their correct name and call them pinner wires. (When I was a kid, a pinner was a tightly rolled joint. Its opposite was a hog leg.) All the resistors in the whole world, and enough alligator clips to fill the Everglades, and a couple of bags of fuses, and a sack of capacitors, and a box of transistors, and my multimeter.

Starting Electronics, Electronics for Beginners, Electronics for Dummies, Getting Started in Electronics. Schopenhauer is right again: “As a rule the purchase of books is mistaken for the appropriation of their contents.”

An Eveready super heavy-duty 6V carbon zinc battery, with its classic black cat logo.

Red and green and yellow and blue LEDs. Even the kid who dropped out of my electronics class knew that Shuji Nakamura had solved the challenge of the blue LED. And why was that a challenge? Don’t ask me, man, I’ve got troubles of my own.

***

Here is my Ohm’s Law Simple Circuits Workbook. What is the voltage in this circuit? What is the amperage in this circuit? What is the resistance in this circuit?

I took my workbook to Florida. Creamy yellows, pastel blues and pinks, bleached whites, stucco, cinder blocks. The flat low buildings and the giant sky. Ibises, herons, egrets, sandhill cranes, crows and vultures. The world of the backward baseball cap.

I was in the Sarasota-Bradenton airport bar. They’d seated us on our plane, then led us back off it. A four-hour delay, they told us. I wasn’t calm, more like numb, but numb was close enough to calm for me to be helpful to the other passengers, who were angry or panicked. They told me about the important appointments and opportunities they were going to miss because of our delayed flight. “I don’t know why I’m telling you this,” they said to me, one after another. I sat in the bar, ate a sandwich, and solved problems in my Ohm’s Law Simple Circuits Workbook. But our four-hour delay became a thirty-six-hour delay, and a horse walked into the bar. I stopped solving problems and I started causing them.

***

Electronics, for three reasons.

One. My COVID lockdown pod included the writer of an electronics textbook. All behaviors are contagious.

Two. Chris Miller’s fantastic Chip War, the 2022 Financial Times Business Book of the Year, with its description of extreme ultraviolet lithography in the manufacture of integrated circuits.

Three. The bonkers ending of Norman Mailer’s The Deer Park, where God says to Sergius: “Think of Sex as Time, and Time as the connection of new circuits.”

All right, I will.

***

I was doing okay until my parents lost their house in Florida to Hurricane Ian the same month my girlfriend was diagnosed with cancer. Suddenly I needed someone to tell me what to do. I needed rule-governed activities.

I started with chess. An ice-world of rules, I told myself, to sustain me in my burning-down life. I took mate-in-one puzzles to the waiting rooms of oncologists and thoracic surgeons, to chemotherapy and immunotherapy infusions. Mate-in-ones are considered a pastime for children. One book had a cartoon squirrel on its cover.

I read Irving Chernev’s Logical Chess: Move by Move, Every Move Explained and The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played and replayed classic games on my little folding chessboard at the dining room table after dinner and read Chernev’s commentary, while she snored on the sofa in a heap of her falling-out hair. She hadn’t cut her hair before treatment, and now it was falling out everywhere, making a mess and driving her crazy, but by now her scalp hurt too much for us to cut it.

On Sunday mornings I played chess with my next-door neighbors David and Austin, now and then stepping away from a game to drive my girlfriend to the emergency room.

***

I thought electronics could be the same way. Predictable outcomes, repeatable results, the artist’s dream of science. I took an electronics class because I wanted someone to stand at the front of a classroom and tell me what to do.

I told one doctor, “I wasted my education. I should have gone to medical school like you, because now I am a full-time nurse, but I don’t have the temperament, the technology, or the support team. I don’t have the expertise, I don’t have the peer group. Because I studied the poetry of Edmund Spenser, like a big dummy.”

An example of my bedside manner: “Will you shut up? I am trying to empty the blood out of your lung drain.”

I stayed up late, watching introductory instructional videos about basic electronics, about resistors. I tried not to drink too much, and failed. Farts were funny, until she farted blood. Until the weight loss, until the sigmoidoscopy, until the colonoscopy, until.

As the immunotherapy-induced rash on her leg worsened, I saw with mirthless self-awareness that the title of the book I was reading, Christ: A Crisis in the Life of God, was doing double duty as Cancer: A Crisis in the Life of John. In tonight’s performance, the role of God will be played by John. But I don’t have the temperament or the technology.

I was having trouble reading, but I could still listen to stories. One afternoon between doctor’s visits, I found myself listening to a sexy one. “I’m too stupid. I’m just a stupid little girl who needs her daddy to tell her what to do. Please. It’s so hard. Everything is so hard. Oh, I’m so stupid, Daddy, tell me what to do. Tell me what to do.”

It was soon obvious to me that I was the girl in the story I was listening to. I disowned my own fear and helplessness and projected it outside of myself, refusing to recognize it as mine, flattering myself that instead I was the omnipotent authority the helpless girl was pleading with. But I was the one who was pleading.

That is not pornography, it is a famous prayer. I’m too stupid, Daddy, please tell me what to do. Our Father who art in heaven, tell me what to do.

***

I was the only nonscientist in the electronics class. It was held in a fifty-thousand-square-foot open facility just over the bridge. Battery engineers, software designers, X-ray technicians. I kept my mouth shut. I think I was assumed to be a scientist, too.

I had an awfully good time. But I didn’t understand much of the lectures, and I didn’t understand most of the questions the other students asked, and I rarely understood the answers to those questions. I listened to the fans of the solder fume extractors.

Photograph by J.D. Daniels.

Here’s the “joule thief” I built by following instructions.

Photograph by J.D. Daniels.

What does it do? It does whatever I tell it to do.

It “can use nearly all of the energy in a single-cell electric battery, even far below the voltage where other circuits consider the battery fully discharged (or ‘dead’).”

Yet again I have built myself. The golem scratches its head.

***

“On Margate Sands,” T. S. Eliot wrote, “I can connect / Nothing with nothing.” I can connect metal to metal with metal: I am good at soldering. I put on my safety glasses, turned on my fume extractor fan, clamped my circuit board, unrolled my little coil of solder wire, heated up my soldering iron, and got to work. One of our teachers said, “We have a winner!” My girlfriend thought it might be due to the summer I had spent learning about welding. I’d taken two safety courses to be allowed to use the metal shop, then a MIG-welding intro, then a more focused and thorough welding course, then a kit course, if you want to call it that, where we all built the same project, a simple grill. Cutting, grinding, drilling and punching, the vertical bandsaw, the belt grinder and belt sander, the hydraulic ironworker, tack welding and stacks of tacks, drag welding, fillet welding, butt welding, cutting and patching, rooster tails of sparks thrown across the room by the angle grinder, pounding headaches from arc flash. I had performed adequately, not excelling but not having any accidents, unlike two of my welding classmates, who were always setting something on fire. Those classes had been years ago by now. But I thought it might be true that I had learned not to be paralyzed by a fear of burning metal.

Then, too, my electronics classmates, as friendly and smart and funny and good-looking as they were, seemed like they might be that commonly sighted species, the Northeastern achievatron. They wanted to get it right the first time and get an A-plus, a gold star, whereas I was confident I was going to do it wrong. So what. I’ll try anything once. I’ll go first. Here, hold my beer.

***

Tell me what to do. I followed instructions and I built little toy desk models. A forty-two-cylinder diesel radial engine model, based on the Zvezda M503 from Soviet missile boats. Before that, a U12 based on the GM 6046 twin-straight-6 from the Sherman M4A2 tank, an H16 based on the Formula One 1966 U.S. Grand Prix winner Lotus 43, and an X24 based on the Rolls-Royce Vulture. I built a toy model of a Schmidt coupling, a constant-velocity joint, a double universal joint, bevel gears, a slider-crank linkage, a sun and planet gear, a Scotch yoke, and a Chebyshev lambda linkage.

I bought a copy of Small Engines and Outdoor Power Equipment: A Care & Repair Guide for: Lawn Mowers, Snowblowers & Small Gas-Powered Implements, and I mail-ordered a used lawnmower-engine power head from an OEM Lawn Boy model 8243AE and a used Toro single-stage Tecumseh AH600 1627 snow-thrower engine to dissect, remembering the happy summer month I’d once spent ruining a weed eater’s two-stroke engine. But did I dissect them? No, I did not. They are still sitting on a rectangle of particle board in the next room. I can see them now.

All of this was playacting and pseudoscience, I see that now. All of it was sorcery. The nurses used telemetry to monitor her vital signs. I bought a blood-pressure cuff and kept a log of my own vitals. I was coming with her, like it or not. Down with the ship.

Tell me what to do, in order to—what? No one knows what I want, and, even if someone did, no one could tell me how to get it. There isn’t any way to get what I want. What I want doesn’t exist.

***

“Burn things out, mess things up—that’s how you learn,” said the cover of one of my electronics textbooks. It was somewhat reminiscent of my old drug-use textbook. The title of this present article is drawn from that textbook’s author, William S. Burroughs, who once asked: “Is Control controlled by its need to control?”

“A friend of the interviewer, spotting Burroughs across the lobby, thought he was a British diplomat. At the age of fifty, he is trim; he performs a complex abdominal exercise daily and walks a good deal.” —Conrad Knickerbocker, The Paris Review issue no. 35 (Fall 1965).

“ ‘Naked Lunch would never have been written without Doctor Dent’s treatment.’ … Burroughs also took up the abdominal exercise system of F. A. Hornibrook—author of the once best-selling book The Culture of the Abdomen (1924)—whom Dent seems to have introduced him to personally.” —Phil Baker, William S. Burroughs (2010).

“Burroughs took a room in the Hotel Muniria, at 1 calle Magallanes, with a private entrance that opened on a garden. He was off junk for the first time in three years, and he was on a health kick. In the morning he did the Hornibrook abdominal exercises he had learned in London, which guaranteed a flat stomach. Then he went rowing in the bay.”—Ted Morgan, Literary Outlaw: The Life and Times of William S. Burroughs (1988).

“The special abdominal exercises that he received from a man named Hornibrook in London, who learned them from the Fijian islanders.”—Barry Miles, Call Me Burroughs (2014).

This would seem to settle the question of what the “complex abdominal exercise” referred to in Knickerbocker’s Paris Review interview with William S. Burroughs was: The Culture of the Abdomen: The Cure of Obesity and Constipation, by F. A. Hornibrook, preface by Sir William Arbuthnot Lane, Bart., C.B., M.S., Consulting Surgeon to Guy’s Hospital, etc.

Now I have on my desk a hardback copy from 1935. It is eighty-nine years old. It smells bad.

And it was on this same desk, with its alarming amount of scorch marks, that I did my electronics self-teaching, such as it was. I didn’t want to simulate circuits using software. Instead, unskilled but insistent, I improvised.

What am I supposed to do with all of these resistors now? I guess I could resist something.

***

The rabbits had eaten the coreopsis. The blue jays were interested in something under the Fothergilla, or maybe it was in the yew hedges. The daphnes in the raised bed were all in bloom. The trilliums had become gargantuan. The tree peony was swelling, ready to open. The clematis was swarming over its trellis. A butterfly, a Zabulon skipper, landed on my hand. A hornet dozed on the windowsill. The cardinal skipped and flitted in the hydrangea. I heard the strange call of a catbird who had learned that sound elsewhere and had brought it home.

I saw and heard all of this while I bound the rotten back fence’s top rail and leaning post together with wire from an electronics hobby kit. Turned out it was good for something, after all.

J. D. Daniels is the winner of a 2016 Whiting Award and The Paris Review’s 2013 Terry Southern Prize. His collection The Correspondence was published in 2017. His writing has appeared in The Paris Review, Esquire, n+1, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere, including The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing.

Beating the Green-Eyed Bastard! – Skinny Artist

“O, beware, my lord, of jealousy!

It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock

The meat it feeds on.”

~William Shakespeare

Jealous much?

Let’s face it, now that almost every artist and their creative brother are online showing off their handiwork, it’s easier than ever to become jealous of …

- their artwork/writing/music

- their sales

- their really cool website

- the hundreds of comments on their blog

- hearing about all of their recent exhibitions and gushing publicity

- not to mention their legions of fawning friends and followers on Twitter and Facebook

I mean, sometimes it’s enough to make you want to crawl back into your creative little hole and hibernate until the coming zombie apocalypse.

Let’s not kid ourselves here. Ten years ago, we all knew that these over-achieving creative folks were out there, but at the same time, we didn’t have to sit there and stare at their virtual trophy shelf every single day.

Not that I’m blaming any of these artists for their success. After all, kudos to them for working their tails off and achieving some level of success in their creative field. I certainly don’t begrudge them that, but that doesn’t necessarily change the fact that sometimes I’m jealous as hell of them.

I can’t even read books anymore…

It’s been said that one of the requirements of being an artist or writer is to fully immerse yourself in your art. Not just diving into your own work, but also the works of others. For writers, this means reading the great works of literature, for musicians listening to the classics in your chosen genre, and for visual artists, this means studying the masterworks of those who came before you.

That’s fine. I have no problem with that. After all, everyone needs someone to look up to and model themselves after. I don’t have a problem with studying the old masters. What I seem to have a problem with, is studying the work of my contemporaries.

You see when it comes to the old dead masters of our craft, I can usually rationalize their success. After all, maybe they received a better education, perhaps they had more time to practice their craft, or maybe they had some wise old mentor who shared some ancient secrets with them. Whatever may have been going on there, they all ended up doing very well for themselves and that’s great. And if nothing else, at least I can take comfort in the fact that since they’re dead, they are not very likely to steal my really great idea for that book that I’ve been meaning to write.

It’s not the old masters who make me jealous… it’s you!

I’m talking about the regular old artist/writer/musician that you just met on Twitter who seemingly has it all together. You know the one I’m talking about here. That artist who just booked that big show, that writer who just published their first book or that photographer who just published a coffee table book the size of Texas [Editor: for our international readers, that’s pretty darn big]

Damn, I wish I would have thought of that! ~Me

Please don’t get the wrong idea here. It’s not that I dislike these creative contemporaries for their success. In fact, some of them are the nicest people you will ever meet, but I still can’t help but feel a little jealous of their success.

Now is this just some kind of flaw in my character — probably. Look, logically I know that we’re not out here competing with one another and I realize that another artist’s success in no way diminishes my own chances of achieving my goals.

I get that.

Now having said that, I still find myself getting jealous every time I read a really good book. I still feel a bit envious whenever I see a younger writer being featured in some magazine article. And I still get upset when someone else comes up with a really good idea that may have been sitting right there in front of me the entire time.

It all comes back to the evil twins of Fear & Doubt

In the end, of course, it’s not about any of them — it’s about me. It’s about me not living up to my own expectations. It’s about me having a vision that seems to be constantly just beyond my reach and ability. It’s about me not always feeling worthy of the path I have chosen for myself. And it’s about me feeling as if I have wasted so much of my time by not starting sooner and getting distracted by endless shiny objects along the way.

The author Julia Cameron put it this way in her extraordinary book “The Artist’s Way“:

“Jealousy is always a mask for fear: fear that we aren’t able to get what we want; frustration that somebody else seems to be getting what is rightfully ours even if we are too frightened to reach for it. At its root, jealousy is a stingy emotion. It doesn’t allow for the abundance and multiplicity of the universe. Jealousy tells us there is room for only one — one poet, on painter, one whatever you dream of being. . . The biggest lie that jealousy tells us is that we have no choice but to be jealous. Perversely, jealousy strips us of our will to act when action is the key to our freedom.”

This constant sense of fear, inadequacy, and jealousy is certainly not something I’m proud of, and the only reason I’m sharing any of this with you is because I suspect that I’m not entirely alone.

So I guess my question to you is….

- How do you not get discouraged by all of this?

- How do you get past that nagging feeling that somehow it has all been done before?

- How do you celebrate in the success of others without getting down on yourself?

- How do you not beat yourself up for losing focus and wasting so much time along the way?

Please tell me that I’m not the only one who feels these things!

DIYDPW #75

Stop 4 Turtles. New Paltz, NY. September 2024 🐢 Turtle Crossing. New Paltz, NY. September 2024 Slow Down 🐢. New Paltz, NY. September 2024 Turtle🐢X-ing. New Paltz, NY. September 2024…