Julia Volchkova | Street Art

Siberia, in 1987.

Since childhood, she has loved drawing and went on to undertake a professional

art education, specialising in anatomy and portraits. She graduated in 2010.

Meet the Gallery Owners: New York’s Artios Gallery

New York City-based art gallery, Artios Gallery, is an e-commerce destination for emerging and established artists. They will be exhibiting at Artexpo New York 2023 at Pier 36. Get to know the gallery owners below.

Eternal Sunshine by Irina-Sheynfeld

Q: Introduce yourself — who you are and what your gallery’s vision is?

A: Founded in 2018 as an e-commerce gallery, Artios showcases a number of emerging and established international artists selected for their unique creative and intellectual vision. The gallery aims to connect beautiful works of art with enthusiastic new owners and provide a platform for emerging artists of all styles and genres. We are working towards achieving this by creating online and physical exhibitions, printing art catalogs and advising our artists on various marketing strategies.

Q: What is your background?

A: Founders Elena Iosilvich and Ellen Opman bring their rich backgrounds to the development and business of establishing Artios Gallery, providing expertise to both the artists they represent and the collectors they serve. Elena Iosilevich (Seroff) is a New York-based artist and entrepreneur. She is the Founder and Art Director of Artios Gallery. Elena studied fashion design at LEX University in Tallinn and received a BA in Decorative art from Kaliningrad Art and Industrial College. Elena is an active member of many reputable art organizations, such as the National Association of Women Artists and the Association of Women Art Dealers. Elena has been living and working in NYC since 1996. Originally from Ukraine, Ellen Opman immigrated to the US over 30 years ago. Ellen holds a business degree from the City University of New York. Before co-founding Artios Gallery, she worked in several international firms in New York and London, UK. Currently, Ellen is combining her business commitments with pursuing a Master’s degree in the Museum Studies field.

Contemplation by Elena Seroff

Q: What is your work philosophy, and how does that impact the gallery?

A: Artios aims to be an inclusive and diverse place. Our philosophy is to provide our clients with various styles and genres suited to various tastes and needs. We constantly search for new talent, be it a local artist or someone who lives abroad. In today’s increasingly interconnected world, an online representation allows us to reach more people worldwide. As part of our strategy, we partner with art-selling global platforms. This partnership is essential for helping to expand our business and giving us a perspective on contemporary art trends and interests.

Q: What artists and art styles do you represent?

A: Artios Gallery prides itself on selecting high-quality, exceptionally talented artists whose unique vision shapes the contemporary art scene. Our artists work in many styles and media, including abstract and figurative oil and acrylic paintings, prints, photographs, and digital art. They come from sixteen countries across South and North America, Europe, and the Middle East. The variety of styles our gallery represents is a testament to cultural diversity, the richness of imagination, and the versatility of methods used to create art.

Summer Vibes by Natalia Koren Kropf

Q: What is the best advice you’ve received?

A: The most important thing is humor. Everything else is nonsense. Here is a famous quote by Walt Whitman: “Keep your face always toward the sunshine, and shadows will fall behind you.”

Q: When you are not working, where can we find you?

A: Being at work is a constant process of our weekday schedule. However, when we are not working, you can find us touring the galleries of The MET or attending the numerous exhibitions and art fairs NYC offers.

Tale II by Alex Shabatinas

Q: What does exhibiting at Artexpo New York 2023 mean to you?

A: First and foremost, exhibiting at Artexpo New York allows thousands of people interested in art to see our gallery. As participants, this exposure allows us to forge new connections with potential clients, artists, and other exhibitors. It allows us to familiarize the audience with our talented artists, showcase their art and tell their stories, and learn more about other exhibitors. We are thrilled to be a part of the most buzzed-about art fair in New York.

Tickets for Artexpo New York 2023 can be purchased here.

Loss of an Art Industry Professional

We are sad to announce the recent passing of one of Redwood Art Group’s long-time exhibitors and friend, Elaine Michelle Joseph, on February 1, 2022, after a long-term health issue. Elaine, along with her husband Michael Joseph, were founders of Artblend, a full-service, art business offering gallery and art fair exhibitions, marketing and promotion, book publishing, and magazine profiles to emerging, mid-career, and established artists from around the world. Elaine and Michael resided in Fort Lauderdale where Artblend was based.

With Elaine as the president and editor-in-chief and Michael as the vice president and publisher, the duo established an exciting business fueled by Elaine’s love of art. It was Elaine managing Michael’s photography career that made Artblend a reality.

Elaine Joseph had an extensive career history in management, marketing, promotion, and advertising. Prior to the creation of Artblend, she worked with several leading companies in the music and entertainment industry as well as major retail stores, including Transworld Entertainment, New England Video, The Musicland Group, Compact Disc World, Blockbuster Video, and Victoria’s Secret. She received multiple awards and recognition for her record-setting accomplishments.

“We are saddened by the loss of a real art industry entrepreneur. Elaine was always impressive, making things happen for the artists that worked with Artblend. She will be missed by all who worked with her and will always be remembered for her positive approach in building an artist’s career,” said Eric Smith, President of Redwood Art Group.

Elaine was passionate about being involved with the Toys for Tots organization and, along with Michael, hosted the local Fort Lauderdale drive for several years. It always culminated with a festive Winter Holiday Party at the Artblend Gallery.

“We were so sad to learn about Elaine’s passing. She will be missed by so many and remembered by those whose careers she launched. Her drive, professionalism, and love of the art world made her someone we were all glad to know,” remembers Linda Mariano, Redwood’s Managing Director of Marketing.

Those wishing to send the family a message of condolence may do so at this link: https://www.forevermissed.com/elainemichelle-joseph/about

On Hope and Dread in Nuclear Times: Ana Vaz’s Long Voyage Out

Please bear with me while I jog our recent collective memory a little: on March 11, 2011, at exactly 14.46 local time, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake shook the very depths of the east coast of Japan. Less than an hour after, a massive tsunami started its catastrophic journey across the ocean, claiming lives and devastating entire towns. Towering waves soon overwhelmed the seawall of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, three hundred kilometres north of Tokyo, and disabled its cooling mechanisms, triggering in turn three successive nuclear meltdowns from March 12 to 15. The triple disaster officially killed 18,000 people and displaced over 470,000; 154,000 of which were evacuated due solely to the nuclear accident.

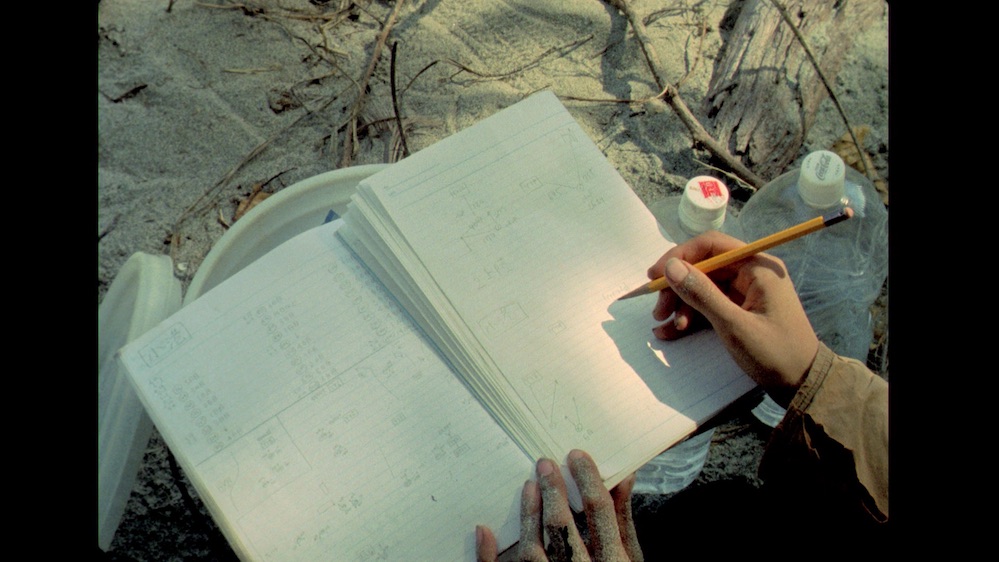

Ana Vaz, still from So long as the sky is recognized as an association (2018).HD and 16mm transfer to HD, color, stereo sound, 15’40’’

We tell ourselves that we know what happened on that exact day, that we have the facts and we have the figures. It’s a control-seeking narrative aimed at countering the unpredictability and strength of nature. But what, then, about the effects, some of them yet to unfold, for human, animal and vegetal life? When do we get to find out about those? Timelines are fuzzy in nuclear spans; the consequences, much like those of climate change, too complicated to envision and thus all too easy to ignore. These, I feel, are some of the questions haunting the Brazilian artist Ana Vaz, who began her spiralling project on the Fukushima disaster back in 2014. This expanding constellation, titled The Voyage Out, gathers 16mm films, HD videos, sound works, text and live performances, all oozing a sense of unstableness and mutability that befits their subject matter. The exact form that The Voyage Out will take in its final incarnation is yet to be seen, although according to Vaz it will assume the guise of a feature film, a medium capacious enough to accommodate its multifarious viewpoints and aspirations. In the meantime, the latest working configuration of this kaleidoscopic endeavour—a teaser of sorts—was recently unveiled at the London-based moving image non-profit LUX, as part of its BL CK B X series.

“You continue to doubt your own madness. Radioactive contamination—which is invisible, which has no smell, no taste—does it really exist? The newspapers, the television, my shrink, my parents: they all tell me that the source of my anxiety, might be non-existent. Is it me whose mind is deranged?” The words of Yoko Hayasuke, a survivor of the disaster who lives in dull fear, become the narrative backbone of the three-channel video installation Mediums (2017), the centrepiece of the exhibition. This perceptive study on trauma and anxiety combines the diaries of Hayasuke, spelt out on flickering red celluloid backgrounds reminiscent of 1960s structural films, with glimpses into a cathartic massage ritual administered in Sendai, a city in the northeast coast of Japan that was flattened by the tsunami. Shot in 16mm, a medium whose texture manages to be both nostalgic and time-less, the images depict a group of middle-aged Japanese women and men shaking under the touch of deft hands. Their bodies twitch, as if erupting in corporeal micro-earthquakes, tectonic movements of the repressed.

Ana Vaz, still from So long as the sky is recognized as an association (2018).HD and 16mm transfer to HD, color, stereo sound, 15’40’’

But not Hayasuke. Where others can only utter formless feelings of dread, she puts words. The young Japanese writer is traumatised by the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and she says so repeatedly. But the world around tells her there’s nothing to be afraid of, that she is overreacting, that the problem is in her mind and not in the air and water that she breathes and drinks, quite possibly polluted with noxious radioactive particles. Could this be a case of institutional, or institutionalised, gaslighting? “It’s not serious, I assure you. You are over-anxious. The lady is not seriously ill, and I am a doctor,” sneers the South American physician to Rachel’s fiancé only a few hours before she dies in Virginia Woolf’s 1915 debut novel, The Voyage Out, which obliquely inspired Vaz’s project.

Today, national and international organisations and government bodies continue to release conflicting reports regarding the extent of the contamination generated by the Fukushima disaster and its effect on humans, earth and oceans. Moreover, because the nuclear incident falls under the State Secrecy Law, which came into force in 2014, independent investigations have been rendered de facto illegal.

Ana Vaz and Nuno da Luz, The Voyage Out Radio Series 2022 ∞ 2222 (2017-18).

Included too in the exhibition were the sound works The Voyage Out Radio Series 2022 ∞ 2222 (2017-18), perhaps the most speculative in the constellation, conjuring up science fiction-like scenarios that explore possible outcomes of the disaster. The three episodes have been produced in collaboration with the Portuguese artist Nuno da Luz, who travelled to Japan with Vaz and crafted an exquisite sound design; an oceanic lattice of field recordings of waves, fireworks, bird calls, bees, drums and rain that transport listeners to shores both real and imagined. The first programme is a faulty transmission from 2222 sent by a time-travelling genderless cyborg stranded on a new island that emerged in the southern archipelago of Ogasawara soon after the major seismic event that started it all. The protagonist begins their transmission with an eerie incantation of radioactive isotopes and their uses in industrial and nuclear products, as well as some of the health hazards they cause. They describe green gradient nights, skies whose former pink and yellow hues have turned a luminous grey because of the radioactive fumes. The voyager tells us that the reason they are reaching out to us via spoken words is to honour the “ancient oral traditions that believed that if we voiced the bad dream we arrested it from happening”. It is a warning message, a whisper from a cybernetic Cassandra that has already seen catastrophe come to a pass.

Yet, in those evoked landscapes, the carcasses of old factories have formed a bed of earth where mutant beans are growing, thriving in fact, while a handful of surviving bees pollinate new radioactive flowers. Meanwhile, mysterious eggs have been laid on the seashore, a host of unexpected creatures buried in the sand. Where did they come from? That’s quite possibly what the group of diggers in the nearby film So long as the sky is recognized as an association (2017) are trying to find out. In it, we only see the back and arms of these researchers, their hands and elbows burrowing in. These are images that go beyond the classic dystopia of death and barrenness. New life forms are conjured up, and the eternal cycle of destruction and renewal enacted once again. In one of the radio programmes, the cyborg describes their inter-temporal voyage from 2022 to 2222 and how, after an period of shock in the face of the expanding nuclear landscape, which was initially seen as “maleficent”, they learnt to accept it, to “live with that trouble”—a subtle rephrasing of Donna Haraway, the spiritual mother of posthuman cyborgs and proponent of learning to live in a damaged Earth.

Ana Vaz, still from So long as the sky is recognized as an association (2018).HD and 16mm transfer to HD, color, stereo sound, 15’40’’

“The Fukushima daisies that sprung […] were freaks of nature, a graceful answer to the disaster, a sign of the immutable fact that live lives on, in all forms,” the cyborg says in their transmission, bringing to mind the film Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)—another lyrical take on how to rebuild worlds and affects in the aftermath of nuclear disaster whose script was penned by Marguerite Duras. In one of the film’s opening scenes, the female character tells of how the soil in the disaster area is teeming with animals and flowers only a few days after the atomic bombings, even if the images that accompany her assertion are documentary shots of the ravaged faces and bodies of the children caught in them.

This archipelago of conflicting viewpoints and complementary stances is what makes The Voyage Out such a compelling project. Vaz might have skewed a conventional documentary stance, but she’s not shying away from the complicated questions or moral conundrums that should go with it. Her approach is comprehensive without being exhaustive, or exhausting. She prods at the politics of secrecy versus the cathartic powers of disclosure while imagining the concrete effects of the disaster on bodies, territories and minds. She indulges in philosophical speculation, but not before having done fieldwork and collected actual testimonies. Her granular strategy is a convincing methodology, a soup of self-sustaining fragments that coalesce under the frequencies of Da Luz’s evocative sound work, which brings it all together in a dance of light, voices and drones. What’s most refreshing is that despite working with such loaded subject matter, Vaz has allowed The Voyage Out to be loose, hallucinatory, sensual. She beguiles us into staring at nuclear and ecological collapse in the face: bleak, phantasmagoric, looming… and yet, she daringly says, brimming with possibility.

This review was shortlisted for the fifth International Awards for Art Criticism (IAAC) and is reproduced with the consent of the IAAC Ltd.

How Burlesque Dancing Helped Me Survive Perimenopause

It all started when the mammogram lady asked me the date of my most recent period. I searched — desperately — for a memory of tampons. Nothing.

“Just roughly,” she said into the silence.

“Eight months ago?” I blurted, knowing it was longer than that. “Is that bad?”

“No, that’s about right for your age.”

“Perimenopause,” she said. “Take a seat please.”

I am the first to admit that I don’t know nearly enough about the ins and outs of my body. I’m not proud of this. But I blame the nuns. Well, one nun in particular: Sister Redempta, my 12th grade biology teacher.

“It’s your souls you need to worry about,” she’d said after instructing us to draw a line through “Chapter 5: The Human Body” in our textbook. “Use a ruler.”

When someone asked — very bravely, I thought — how we would learn about our reproductive system, Sister said all we needed to know was that intercourse existed purely for procreation. And doing it before marriage was a one-way ticket to hell.

“Your body is a temple,” she’d said, from the safety of her navy blue habit. And this meant never, ever, under any circumstances, bringing attention to it — especially to the female bits, like breasts and hips. Besides, she scowled, physical beauty was fleeting. And wasting time on pursuing it, sinful.

“Remember Delilah?” We all knew things had not ended well for Delilah.

My social awkwardness and love of the library made it easy to follow Sister Redempta’s guidelines for good living. By the time I was 23, I was still a virgin who wore overalls and sensible shoes, possessed no makeup and cut my own hair. Not too long after that, I fell into marriage and motherhood, still largely oblivious to the workings of my body.

But now there’s Google. While I waited for the mammogram lady to call my name, I typed “perimenopause” into my iPhone. And there it was, all the madness of the past two years.

It had started in my mid-40s with a kind of sadness that had slithered up my spine, keeping me awake at night. This was immediately followed by guilt. I had a husband who loved me, children who were healthy and magnolia trees in the garden, for God’s sake. What right did I have to be sad?

Then the tears arrived. So many tears. I’d catch a glimpse of myself in the rearview mirror. Tears. Leonard Cohen would play on the radio. Tears. Sunset. Tears. What the hell?

The night sweats started around the same time. At first, I’d thought they were nightmares; I’d had those as a child. But then they arrived during the day, too. I’d be at Safeway, putting mushrooms in a paper bag, and I’d start burning up, wanting to rip off my clothes right there in the fresh produce section.

Next came the inexplicable urge to just get in the minivan and drive. Anywhere. And never come back. I thought I might be going insane. But I had just been given a name for all the crazy shit going on inside me: perimenopause.

I was reading about estrogen on my phone when a little box popped up on the screen. “Burlesque Classes!” The letters were sparkly. I took a screenshot just as the mammogram lady called my name.

Two nights later, after loading the dishwasher and feeding the dog, I hopped into the minivan and crossed the bridge. I had signed up for the classes online, right after my mammogram. I had no idea what we’d be doing, but I’d seen the movie “Burlesque.” Christina Aguilera and Cher seemed to be having a good time. Besides, it would give me an excuse to escape the suburbs, even for just a few hours.

I tippy-toed up the linoleum steps into a studio with hardwood floors and velveteen sofas — into a new world.

There were seven of us: six in their 20s and me, 47. Our instructor, Melody, had flame-red hair and a snake tattoo wrapped around her left thigh. And she was mesmerizing. She told us about bold women through the ages who had thumbed their noses at society’s rules for how they should behave.

Melody demonstrated hip rotations. Everyone else’s hips moved. Mine remained piously rigid.

And then it was the “peel,” where a dancer sensually removes an item of clothing like a glove. I watched in awe as Melody took off her stockings with her fingers, her toes, her teeth! I had never worn stockings, and putting them on was hard enough. Now I had to take them off? To music?

Over the next few weeks, I destroyed 20 pairs of London Drugs thigh-highs. And then one night I did it. It wasn’t sexy. Or pretty. But I didn’t fall over. The last time I’d felt this proud was right after childbirth. That night, back in my little cottage in the suburbs, I slept for the first time in years. No weeping. No night sweats. Pure, glorious sleep.

In the fourth week, with no warning, Melody handed us each two tiny sparkly circles, with sequins and tassels.

“Tops off, ladies,” she said, pulling her shirt over her head. I tried not to stare at her perky pasties.

This was when I discovered that our classes would be culminating in a performance, on stage, during which we would peel off our clothes, one item at a time, to reveal, finally, our pasties. Simply put, I would be exposing my middle-aged boobs to an entire theater of strangers. Sweet Jesus.

The peculiar thing about this whole adventure was that, despite being twice the age of the other dancers, I never felt old. In the world of burlesque, age is revered — unlike in real life, where women nearing 50 are expected to slip quietly into invisibility. Many burlesque legends, I learned, performed into their 70s and beyond, to standing ovations and raucous adulation.

Despite my awkwardness, I could not wait for Wednesday nights. I adored the girls. They showed me how to do my makeup, curl my hair, glue my lashes. They even taught me how to create the illusion of cleavage using glitter.

I ran into an old friend at Safeway one morning. “Have you had Botox?” she whispered. “You’re, like, glowing.”

I smiled demurely, shook my head no, and thanked her. I wish I’d had the courage to tell her the truth: that the glow came from dancing nearly naked. But I had told no one what I was doing. Good wives, responsible mothers, did not undress in public. I assumed it would be a once-in-a-blue-moon thing anyway. That’s how I arrived at my stage name, Luna Blue.

Twelve weeks after my mammogram, I found myself backstage, wearing my 17-year-old daughter’s little black dress, sheer thigh-high stockings, stilettos, and black satin Audrey Hepburn gloves.

The music started. Holy Mary, Mother of God. I stepped into the spotlight.

The gloves went first. Then the heels. Next were the stockings. I didn’t fall over! I reached behind to unzip the little black dress, revealing the scarlet corset that was more expensive than anything I’d ever owned. Finally, it was time to remove my little black bra, with its red satin ribbons. I closed my eyes. Please Jesus, don’t let me lose a pastie.

With the final beat of the music, unable to delay any longer, I tossed the bra in the air. The audience went wild. And just like that, the fear was gone. I felt beautiful.

I was invited to perform again. In different venues around the city. “Once-in-a-blue-moon” be damned.

And something even more unexpected happened: The tears stopped. The odd spectacular sunset still made me weepy. But “Hallelujah” no longer sent me into convulsions. I was still sometimes overcome by hot flashes while doing the laundry or walking the dog. But not once did I have a flash while dancing. And I stopped dreading bedtime, because I could sleep.

My daughter turned out to be thrilled upon discovering that her little black dress was being used around town. We were driving home from school one day when I told her about Luna Blue. There was a moment’s silence. And then she said, “You know, Mom, most people, when they have a midlife crisis, they get a fast car.”

With all the wisdom of a 17-year-old, she added, “But if burlesque makes you happy, you should do it.” So simple.

That’s exactly what burlesque had done: made me happy. It also challenged some of my most deeply held beliefs about what it means to be a “good” person by showing me that my body was a source of pleasure and delight, something to be celebrated.

One night, almost a year after that first performance, I waited in the wings at the opening of a new club.

“Luna Blue,” the emcee announced, and I made my way — slowly — toward an old Ikea chair that I’d painted white for the occasion. Rod Stewart started singing “I Wish You Love,” and I looked at the crowd from under my fake lashes.

I untied the halter ribbons, tugging them loose. I had bought this dress in the old-lady section of Sears. It was deep purple and flowed to the floor in elegant folds. In a little circle I danced, finally turning my back to the crowd as I shimmied out of it.

Though my hips still refused to rotate, I was learning to understand my body. To listen to it. Adore it. And the beauty of burlesque, I discovered, was that there was no right or wrong way of doing it. No ideal body or dance style. All it demanded was the naked truth, in all its glory.

As Rod sang about the “shelter from the storm, a cozy fire to keep you warm,” I turned back toward the audience, holding the purple fabric in front of me — the final tease. Directly in front of me stood a young woman, eyes sparkling, smiling. She reached one hand toward me. I stepped toward her, our fingers almost touching. Energy vibrated between us.

As the music ended and the applause began, I ran my fingertips across the length of my body. Yes, Sister Redempta, my body is a temple — a magnificent temple indeed.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

Capturing Dance – and Dancers’ Lives – on Film

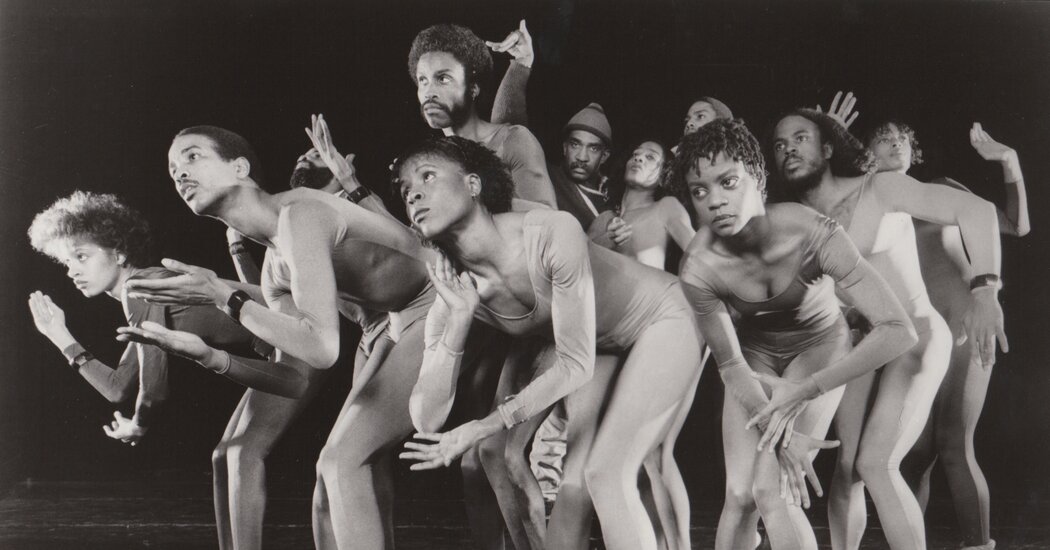

Courtesy of Lewitzky Dance Company records, Special Collections, USC Libraries, University of Southern California

Filming dance is a tricky business, with many moving parts. It calls for complex creative collaborations among people with diverse skills, and often requires a lot of space and piles of money. Add in the exigencies of a worldwide pandemic and you have a recipe for chaos. It’s a kind of miracle that this year’s Dance on Camera Festival, playing February 10 to 13 at Lincoln Center, is very strong.

Co-curated by Michael Trusnovec, Shawn Bible, and Nolini Barretto, of the Dance Films Association (DFA), the venerable festival, now in its 51st year, assembles 30 movies, long and short; documentaries; and filmed choreographies from around the world into more than a dozen programs, almost all rewarding attention. At least half are works by women. Only one of these, the festival’s opening feature, explicitly credits the organization Women Make Movies, but the female form, women’s feelings, and a certain sensuality permeate the whole enterprise.

Astutely assembled, Dance on Camera (DoC) opens with Call Me Dancer, a film about men made by women and nurtured over years of preparation by DFA Labs, the association’s own work-in-progress initiative. Leslie Shampaine and Pip Gilmour’s 84-minute feature documents the emergence of Manish Chauhan, a young performer from Mumbai, son and grandson of taxi drivers, whose roots are in break dancing but who is lured into a ballet studio in his early twenties and soon falls under the spell of an imposing Israeli teacher, Yehuda Maor, who grew too tall for a ballet career but made his mark as a modern dancer and master instructor. Over 70 when they meet, having performed and taught in Israel, San Francisco, and New York before settling in Mumbai, Maor recognizes Manish’s gift and finds him the resources and connections he needs to build a career, even with his late start.

© Jeff Malet

Call Me Dancer follows Manish as he trains and struggles and meditates on his obligation to his close family, who live two hours outside Mumbai. Maor locates a patron who covers Manish’s living costs; an offer of film work allows him to contribute to his family’s expenses and eventually pay for his sister’s wedding. The film juxtaposes dramatic studio footage with street scenes and interludes in Maor’s modest digs, where, as time passes, Manish winds up caring for his aging teacher. “Dancers are unique human beings,” opines Maor, who has shoehorned another of his Mumbai prodigies into the school at London’s Royal Ballet. “In three years, we’ve done what takes nine!” he exclaims, speaking of preparing these lads for professional training. (That dancer, Amir, is now with the Miami City Ballet.)

© Neil Barrett | Courtesy of Shampaine Pictures

Maor sends Manish to Israel’s Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, where the young Hindu observes, “They don’t want princes … they just want normal human beings.” He lives on a kibbutz, learns some Hebrew, and introduces his fellow dancers to the spicy wonders of Indian cuisine. We watch him nurse himself back from a shoulder injury, look after the aging Maor back in Mumbai, and, finally, travel, mid-pandemic, to New York and then to Washington, D.C., where he performs at the Kennedy Center. When you watch this feel-good film, stay through the delightful credits — the folks behind the cameras get up and dance.

When a choreographer displays a dance, it’s up to each spectator to choose where to look. When that same choreographer allows her work to be filmed, the cinematographer makes that decision, directing the viewer’s eye to the choices made with the lens.

Call Me Dancer represents the strongest slice of the films on offer: works that engage the politics and economics of the dance world. These films often include talking as well as moving; they stretch the genre, the performers, even the audience. Another subset includes filmed dances. When a choreographer displays a dance, it’s up to each spectator to choose where to look, and how much to take in of the action spread across the stage. When that same choreographer allows her work to be filmed, however, the cinematographer makes that decision, directing the viewer’s eye to the choices made with the lens. The collaboration between filmmaker Jeremy Jacob and choreographer Pam Tanowitz is a prime and lovely example of this process. Their 26-minute I was waiting for the echo of a better day, filmed outdoors on the campus of Bard College and a highlight of Saturday evening’s Program 6, of shorts by local artists, situates some of my favorite dancers (Melissa Toogood, Lindsey Jones, and several others), in Reid & Harriet’s bright, translucent costumes, among trees, plants, and stone walls on the banks of the Hudson River.

“Suck It Up.”

Alan Jensen

Another standout on that program is Baye & Asa’s 12-minute Suck It Up, which explores male responses to a barrage of gestures of toxic masculinity — it’s both funny and very sad. Two of the works in this festival recently won awards at Dance Camera West’s (DCW) 2023 festival, held last month in Los Angeles. Bridget Murnane’s Bella, the main event on DoC’s second program, won for best feature documentary; it profiles Bella Lewitzky (1916–2004), a pioneering California choreographer who forged a career even while quitting several high-profile assignments. The primary muse of Lester Horton, who established modern dance on the West coast in the 1930s, Lewitzky left him to develop her own work — he never spoke to her again. The daughter of a socialist painter, she was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, in the ’50s, and refused to name names. “I’m a dancer, not a singer,” she famously told reporters. Appointed dean of dance at the newly formed California Institute of the Arts, she quit when she realized the campus didn’t have any performing spaces, which her troupe desperately needed. In the late ’80s, an attempt by wealthy Angelenos to build her a downtown dance center went south when the moneyed supporters demanded a greater role for ballet, and she “knew I had to leave.” The painstakingly assembled building site is now a food court and parking garage. Lewitzky danced, herself, until she was 62.

In 1990, the National Endowment for the Arts instituted an anti-obscenity pledge, required of all recipients of federal arts money. (“None of the funds … may be used to promote, disseminate, or produce materials which … may be considered obscene, including, but not limited to, depictions of sadomasochism, homo-eroticism, the sexual exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts which … do not have serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.”) Lewitzky refused to sign it, printed it on T-shirts with a red line through the text, and sued the NEA. She won, and eventually got the money, but the struggle was the beginning of the end of her company, which closed when she retired, in 1997.

Courtesy of Lewitzky Dance Company records, Special Collections, USC Libraries, University of Southern California

Additional highlights of the festival include the other DCW winner, Ghostly Labor, a 13-minute film by John Jota Leaños and Vanessa Sanchez depicting, in tap dance, flamenco, and other percussive forms, the history of agricultural labor in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, with musicians and dancers deployed in the fields they till. Another is Maurya Kerr’s 23-minute Saint Leroi, a surreal meditation on Black history, violence, and American decay and a powerful indictment of racism. Future Futures, a 38-minute work by Brian J. Johnson and Vancouver’s Company 605, set on and around the campus of Simon Fraser University, is a chilling evocation of where our digital obsessions may lead us: rigid bodies dissolve into pixels and burst into flame.

There’s much more, a lot of it very good. An all-access pass for the four-day event is available for $79 ($39 for students). Use one to see the dozen or more programs, culminating, on Monday, with a 40th-anniversary screening of Adrian Lyne’s Flashdance. ❖

51st Dance on Camera Festival

February 10 to 13

Film at Lincoln Center

Full schedule available at

filmlinc.org

dancefilms.org

Elizabeth Zimmer has written about dance, theater, and books for the Village Voice and other publications since 1983. She runs writing workshops for students and professionals across the country, has studied many forms of dance, and has taught in the Hollins University MFA dance program.

– • –

NOTE: The advertising disclaimer below does not apply to this article, nor any originating from the Village Voice editorial department, which does not accept paid links.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting the Village Voice and our advertisers.

Garth Fagan’s Archives Are Acquired by Library of Congress

The 82-year-old founder of Garth Fagan Dance, a company that includes dancers ranging in age from their teens to their early 70s, shared the secret to a successful multigenerational troupe: not just physical toughness, but also spiritual and intellectual wellness.

“You get youngsters with all their bounce and carrying on, and adults who are just making it work with great difficulty,” Fagan said.

Fagan, a Jamaican-born choreographer known for threading ballet training and discipline into his Afro-Caribbean movement, is also the longest-running Black choreographer in Broadway history because of his work on “The Lion King.” His choreography for that musical won a Tony Award in 1998.

His expansive work captured the attention of the Library of Congress, which announced this week that it had acquired a collection documenting Fagan’s legacy, including early photos of him as a teenage dancer and full visual recordings of works like “From Before” and “Prelude.”

The collection includes more than 30 years’ worth of footage of Fagan’s creative process with dancers, along with handwritten rehearsal notes, programs, posters, letters and audio recordings.

The library already holds collections of works by dance luminaries including Martha Graham, Erick Hawkins, Bob Fosse and Alvin Ailey.

Fagan’s choreography for “The Lion King” has been seen across the world, with the musical having been performed on every continent but Antarctica, producing nearly $10 billion in revenue. At the library, the archive includes souvenir programs, playbills and posters from “The Lion King.”

“I’ve seen it and rehearsed it all over the world in different languages, cultures and I get the same thrill every place I go,” Fagan said.

When his dance company, which was founded in 1970, returned to the Joyce Theater in November to perform six works, Gia Kourlas, the New York Times’s dance critic, called Fagan’s techniques “impossible until you see them with your own eyes.”

Fagan explained that his choreography requires dancers to build full-body strength, with an emphasis on the lower back. William Ferguson, the company’s executive director, once performed a work, “Dance Collage for Romie,” using crutches.

“One of the things that really inspired me to work to get our archive at the Library of Congress: the opportunity for the technique to be preserved in perpetuity,” Ferguson said.

Libby Smigel, a dance curator at the Library of Congress, said that after half a century of running a contemporary dance company, Fagan was finally getting the recognition he deserved.

“What we really don’t have is this hybridization of traditional forms with the classical ballet training, which now can train artists like racehorses,” Smigel said.

Most dancers retire at age 40, but Smigel said she admired the strength training and undulating movement synonymous with Fagan’s choreography that keeps the dancers’ muscles limber well into their later years.

“I wish I had been doing it all this time,” she said.

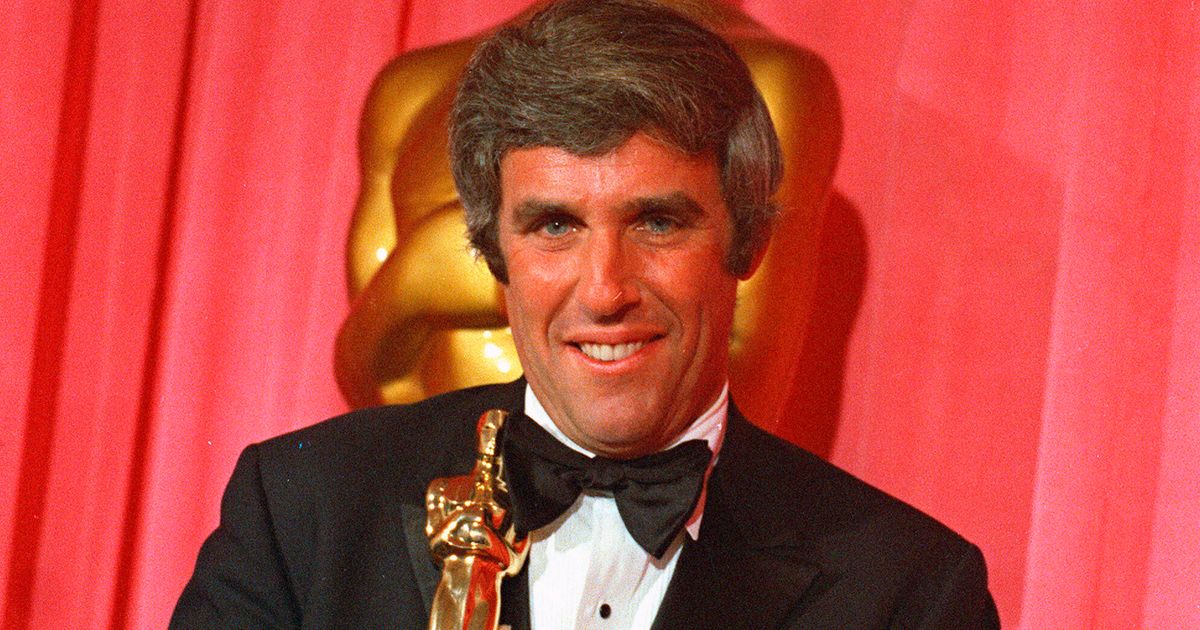

Burt Bacharach’s Death Inspires Symphony Of Twitter Tributes

Songwriter Burt Bacharach may have died, but his music will live on, if the reaction to the news is any indication.

As of Thursday afternoon, neither of Bacharach’s best-known collaborators, Elvis Costello and Dionne Warwick, has officially commented on his death.

However, Costello posted a tweet on Jan. 10 promoting an upcoming album of their compositions that honored him and his work just the same.

Collapsing Time • VAN Magazine

A pioneer of modern electronic music, Morton Subotnick not only encouraged technical innovations but defined new sonic paradigms for the creation of electronic music. Approaching his 90th year in April, he remains as energized and dynamic as ever. As a tech geek and extreme music fan during my high school years in the late 1960s, I liked the idea of electronic music more than the actuality of what I was hearing from such places as the Columbia-Princeton studios. Listening to Subotnick’s “Silver Apples of the Moon” exploded everything in the best way. The work made it clear that Subotnick understood pulse and physicality as many academic composers never could. His followup album, “The Wild Bull,” was a powerful anti-war statement, visceral and exciting. I continued to follow Subotnick’s work and our paths crossed many times over the years. In March 2022, he performed a monumental concert with the Berlin-based video artist Lillevan at the Abrons Art Center in New York’s Lower East Side. I spoke to him after the performance. Subotnick has an exceptional memory, and our talk was extremely detailed.

VAN: How would you describe your approach to performing with live electronics?

Morton Subotnick: My metaphor for the live performance is a conductor. I’m the conductor and the composer and the orchestra, and the orchestra is already playing. I don’t play the orchestra, I conduct them. I play at the highest level: who is gonna play what, when and how. And I can do that and think and process, but if I’m doing this or that with a button, my brain is now located at the end of my finger, not on the whole score.

It’s taken me a while to figure that out, to get that metaphor straight, and it’s very clear now, so I prepare my work that way. That’s where the whole notion for the Buchla was [speaking of Donald Buchla’s first synthesizers, made in 1964–65—Ed.]. It was this machine that was more like an analog computer than a musical instrument. The big change was after I did “The Wild Bull.” I realized with all the ability to move your fingers and do all that, I left a very important control voltage out: my voice. So I called Don and told him I needed a control voltage from my voice. He said, “Oh, I can do that.” And I think it was less than two weeks, and I had an envelope follower so I could turn my voice into a control voltage: I could do real-time control of files and started to build control tracks. So now I could make a thing where I was going, Ooo, Uh, Ooo, a, and it would go, Trtrddtrde.

Do you think that a particular use of electronics in contemporary music was inevitable?

Talking 1959–61: At that time, all of us, including myself, imagined music as marching on, all the way back to Schoenberg and the first part of the 20th century where he was saying, “Now that I’ve made the 12-tone technique, I’m assuring the grandeur of the German composer for 100 years.” Boulez and those guys, Berio and all, they started with Schoenberg and then they discovered Webern. Boulez wrote an article that starts “Schoenberg is dead—long live the king!” The king was Webern, and that was the beginning of the post-Webern movement. When you look back, that’s like 30 years after. [Webern] didn’t even make it to 100 years, but they thought that was the future! So when you get to the beginnings of electronics, even Stockhausen and his earliest [electronic] work, the “Studies,” were all basically post-Webern technique. The only thing he changed is that he did it with oscillators and made fresh tunings. But they’re really dull.

There was no concept of rhythm or meter either.

They got rid of the name! I don’t use meters either, but they got rid of the concept of a meter and said “duration.” Time was duration, not beats. I don’t use meters either because I don’t like dance music, but I do use pulse, and the resulting beats have more wildly varying meters than Stravinsky. They’re regenerating new beats all the time, new accents. When I did “Silver Apples,” I was after a new era, with a new new music, not a new old music. You couldn’t do it; you can’t do new new music with an instrument that already exists. You can say, Play whatever you want on a piano, but the tuning and its sound and the way it operates, it belongs to an older time. You need a new instrument for it, and so the only way to do that was to create something where you could make new instruments for every piece. I was trying to figure out what the fuck new new music is…and I realized I didn’t know.

What I know now that I didn’t know then is that it’s not possible. We’re not geared to it, because music is part of us—we get it so early in life that we’re not geared to something new. When I started “Silver Apples,” I began to make new metaphors for music, and I said, A piece of music is not a piece of music, it’s a record. There’s Side One and Side Two, and you could do either side. Side One will be about pitch, Side Two will be about time.

The very opening of it is an excellent example, where there’s scat singing. That’s where you get the jazz, it was bebop [scat sings]. And I called that “pitches which are disjointed,” they’re not connected to each other. Then I had another take which was “pitches which are close to each other.” They were scalar, but they weren’t in scales. I had nothing that could make a scale so I was doing it all by ear. Then the second side. I said, “Well, where do I go? This would be a good place for a sequencer: I’ll get a kind of groove going.” And I got it set up and then I played it. It took me from two weeks to a month-and-a-half for each section, it took me 13 months to make “Silver Apples.” And in each of these little recording sessions, I would have a patch that would be going continually, because if I turned it off, I didn’t know what would happen. I had the little groove pattern going that was different to start with, but it didn’t have an absolute meter until after about two or three days and I then pruned it down. It blew my mind! I couldn’t get my body off of it, it was just great because it was not just a beat and not just a groove, I mean I grooved it, so it was just the right tempo and I played with it, so it was all there, plus I had another sequencer that would just bring in another beat, a low note. Anyway, so there it was…but it wasn’t the end.

How did you develop “As I Live & Breathe” with Lillevan?

We never had a strategy because the whole idea of the piece was very short and simple: I start out with a breath with the light on me, and as I actually breathe, the first sound, there’s silence and darkness. Then he makes an image. Silence, darkness, and then I do it again and so does he. Then as we repeat we begin to collapse the time until there’s no time at all between our actions. He takes a cue from me when I interrupt him as I’m beginning to do it. I’ve added more material now because it was rather crude the first time. But that’s the only strategy we have between us: I give him what I’m doing when I think of what I’m doing. He develops his stuff separately and then we come together.

Did your work intersect with that of John Cage and David Tudor?

At the Tape Center we did a Cage & Tudor Festival in 1963 because the University of California-Berkeley had decided you couldn’t use John Cage’s name in a music class—because it wasn’t music and it took away from what they were doing! So we got hold of Cage and Tudor. I’d never met Cage. We did a six or seven day festival with a concert every night, and Pauline Oliveros and Ramon Sender and I traded off, running the Tape Center. It was Pauline’s turn to do publicity and she did it like mad: We were on CBS television. When we got to concert time, our auditorium only sat 100 people, and people were in line around the building, so we had to repeat it at 11 o’clock at night. We filled the auditorium six or seven nights in a row, two nights, two concerts, and the second concert started at 11:30 at night, because David was so slow setting up. We were just going crazy.

At the last concert, we did Cage’s “Concert.” It’s all the instruments, we had about 11, 12, 13 instruments. His view was that you take a task on, you do it the best you can, and as truthfully as you can. He changed the instructions from time to time because they didn’t work, but that was because they were incomplete. When you get to something like the one with the electronics in it, “Cartridge Music,” that’s really complete. You would do exactly what he says and nothing else, not because he’s imposing himself, but he’s making instructions that will allow…he just hated the idea of improvising.

Articles like this, straight to your inbox

Processing…

Success! You’re on the list.

Whoops! There was an error and we couldn’t process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.

So did Morton Feldman.

Yeah, I was with him when he did “Piano,” I think that was one of the first, if not the first long piece. I was staying with him in his little apartment in Buffalo for a couple of weeks when he was writing it. I would go in and he would be playing and have his cigarette dangling with the ash falling on the keyboard, and he would play over and over until he could get each chord—tuung!—just the right dynamic so that he was really happy with it and then put it in the score. That started him on this approach. He had done the open form pieces where he just did numbers and things, and he was one of the first to convert to writing everything down.

He was really important to us at that time. I got to know him extremely well. At one point when I was teaching at CalArts, I was starting to pull away. I was going to go to half-time, and my relationship with the school was always such that I was close to the president and they would listen because I had helped start the place. I said, “I want my contract to remain intact, but I’m not gonna be here the second term. I want to choose who comes in.” They agreed to that. So I think the first person I chose was Morty and I got a call from him, and he said he’d just found out that I had wanted him to be there but I wasn’t gonna be there when he was coming. He said, “Can we have lunch?” He said it was very important. So we went to lunch and he started talking as he did, and I said, “Morty, you just wanna tell me something important, you better do that now, before you forget,” and he looked at me and said, “Why aren’t you coming in to teach?” I said, “Well, I don’t have to. We’re living cheaply and I’m making enough from my work that I don’t have to come in and teach.” Then I mimicked him: “And why are you coming in to teach? You don’t need to.” He said, “I’m lonely.”

Even at the time, I’m still touched by the way he said it. These are not words you would think would come from him, right? It was such a shock, a kind of an impulse, just a reverberation, and it went through my body. That just brought tears to my eyes.

When we first brought him to CalArts, we had Cage and Feldman and Lou Harrison, and that was our first festival, that’s when Joan La Barbara and I got together. Cage would only come if we brought Joan. We were doing [Cage’s] “Winter Music” with like 25 pianos scattered all over the place in the main gallery, and Joan was on one side singing the solo for voice. It was really gorgeous, [with] long silences, and we were all playing piano, and every once in a while, these little flutters, like a bird, coming from Joan. The audience was on pillows between all the pianos. It went on for about 45 minute. At a certain point, we begin to hear a [imitates snoring]…Morty Feldman was sound asleep!

What about your New York stories?

Going back to my New York days, my original idea was to stay in the studio and never leave, and once a month people could come in and listen to what I was doing, though I thought that probably was not a good idea. In fact, I might have ended up doing that, staying at home, if Jac Holzman hadn’t come in and given me that commission to make “Silver Apples.” I didn’t believe that it happened and I couldn’t believe it was a success either.

I wanted to buy [a copy of the] record. So I went into 8th Street Records in a basement on 8th St. I said to the clerk, “I hear there’s this record ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon.’” He said, “Yeah, but it’s shit.” He then said, ”We’ve sold it out, I don’t know why they’re buying it. I can show you some really good stuff.” And he brings out the Columbia-Princeton records… I said, “No, I really want the ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon.’” He said, “Maybe we have one more copy,” so I bought it. I walked in a giant, I walked out a midget. It really put me in my place. I really love him for that. I don’t think he did it on purpose, but it was good. ¶

Update, 2/11/2023: A previous version of this article omitted the name of composer Ramon Sender, who ran the Tape Center along with Subotnick and Oliveros during the Cage & Tudor Festival. VAN regrets the error.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 650 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Related

Rihanna Returns at the Super Bowl Halftime Show: What’s at Stake?

Seven years later, that has all fallen away, and its reputation has solidified as a modern pop classic, highly influential for opening the doors for major stars to make looser, stranger and more ambling records that weren’t overly retrofitted to radio play. SZA — who appears on the mood-setting opening track of “Anti” — certainly followed in its footsteps with “CTRL” and her current smash “SOS.”

But the most thrilling part of “Anti” was Rihanna’s voice, which had a new, bluesy huskiness; songs like the doo-wop-tinged “Love on the Brain” or the libidinal croak of “Higher” reveled in its raspy grain. She’d transcended the drama and placed the focus back on the music. And then, it stopped.

AT THE GOLDEN Globes last month, the host Jerrod Carmichael couldn’t help but speak to Rihanna directly when he spied her in the audience. “Rihanna, you take all the time you want on that album, girl,” he said. “Don’t let these fools on the internet pressure you into nothing.”

She was there, actually, because she did have new music — the lilting ballad “Lift Me Up” from the “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” soundtrack, nominated for original song. “Lift Me Up” is soulful, elegiac and gently haunting. It’s also an underwhelming, relatively tepid comeback. Movie theme songs don’t always knock audiences’ hair back; but for Rihanna, the expectations were high.

In its current, hypothetical state, R9 is perfect. It could be (as she hinted years ago now) an uncompromisingly sprawling reggae album. Perhaps it’s a tight, no-filler return to Rihanna’s days of aerodynamically engineered pop bangers. Maybe the guest list is stacked; maybe the album has no features at all. It’s everything to everyone, because it is not yet anything at all.

Her Super Bowl performance, too, is currently charged with a similar sense of dazzling possibility. Will Rihanna’s live comeback be a tantalizing introduction to her next era, or a nostalgic look back at her history-making hits that leaves people wanting more? All that’s left to do is, well, exactly what we’ve been doing all along: wait (a little longer) for Rihanna.

Audio produced by Kate Winslett.