Office National des Forêts Blends Urban and Natural Settings

Thoughtful architecture has the power to reflect and reinforce the natural or urban environment of which it exists. Design, materials, and spatial planning come together to create buildings that harmonize with the landscape rather than dominate it. Whether seen in small projects such as Fallingwater or an extension to a public structure such as the Oslo Opera House, there will always be opportunity for architectural integration. In the case of the Office National des Forêts, designed by Atelier Delalande Tabourin, in Versailles, the expansion takes this concept to new heights. Positioned near a railway and bordering forest, the building embraces its setting, seamlessly connecting the built and natural worlds.

The structure reflects the activities of the forestry office, with its form and materials carefully chosen to blend into the forest context. The space invites both employees and passersby to engage with the building in an immersive way, with each element designed to highlight the craftsmanship involved in forest management.

The roof and facade are constructed from locally sourced wood, specifically chestnut, which has been carefully processed to fit the project’s needs. The wood comes directly from the Versailles forest, and its preparation involved a meticulous timeline to accommodate the drying period required for the material.

Inside, the pavilion is organized clearly, with spaces defined by solid wood blocks, guiding movement through darkened corridors that contrast with the natural light flooding the office areas. Custom-designed furniture and signage, made from wood, further connect the space to the forest environment, referencing the markings traditionally used by foresters.

The pavilion’s recessed position, combined with an extended wooden canopy, helps protect the interior from summer heat, while bio-sourced insulation and natural ventilation eliminate the need for artificial cooling. In the winter, a biomass heating system ensures energy-efficient thermal comfort.

For more information on Atelier Delalande Tabourin, visit atelierdelalandetabourin.com.

Photography by Maxime Delvaux.

The Paris Review – New Books By Emily Witt, Vigdis Hjorth, and Daisy Atterbury

Erin O’Keefe, Circle Circle, 2020, from New and Recent Photographs, a portfolio in issue no. 235 (Winter 2020) of The Paris Review.

I did not have a good time reading Vigdis Hjorth’s novel If Only. I felt, in fact, kind of abject—but something about the novel compelled me forward, in a way that sometimes actually confused me. I found myself reading fifty pages, putting it down, picking it up a week later and once again being unable to stop reading, then abandoning it for another week. It was a discomfiting instance where in returning to the bleak narrative world of the novel I felt almost like I was mirroring the behavior of its main character, Ida, who returns again and again to a love affair that seems to offer her nothing but pain. Why was I reading this book that made me so angry, uncomfortable, irritated? Because it was, maybe, the kind of discomfort that can reconfigure certain aspects of the way you see the world, whose insights or the shadows of them seem to recur long after you’ve closed the book—and so they have, as I thought last night of an image from it, Ida and her lover at a restaurant in Istanbul, gorging on champagne, telling the waiter they were just married even though they weren’t.

If Only—published in Norwegian in 2001, but published in English translation by Charlotte Barslund for the first time this month—is a novel about obsessive love. It is one of a spate of recent novels that take all-consuming desire as a theme: Miranda July’s All Fours and Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos both deal with a passion that veers into misery at times, the kind of passion that is transformative only because it shatters lives. But If Only is by far the bleakest of these; in fact, it is one of the bleakest depictions of a relationship I have ever encountered. The affair obliterates Ida; it cuts her off from the people around her, including her young children; it makes her act erratically and occasionally dangerously. The relationship has many of the same qualities as prolonged substance abuse—and it is no coincidence that Ida and her lover constantly binge on alcohol, too. The novel offers neither redemption nor transcendence as its resolution. And yet Hjorth makes this relationship and its aftermath legible to us as a part of the human experience—one that we can’t extract from the type of love we do consider desirable or healthy. At the end of the book, we might find ourselves wondering, as Ida does: “If only there was a cure, a cure for love.” And we might realize, even as we wish this, that we don’t actually mean it at all.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

I want to recommend the final, fourth volume of Michel Leiris’s autobiographical project, The Rules of the Game: Frail Riffs, recently published by Yale’s Margellos series. Lydia Davis—whose fiction, essays, and translations of Proust and Flaubert amaze me—rendered the first three volumes; volume four is excellently translated by Richard Sieburth. Alice Kaplan has written an incisive essay on Leiris, and Frail Riffs, for the current issue of The New York Review of Books. Alice K. is another international treasure whose books will be known by anyone who reads The Paris Review, I would guess. Especially, but not only, The Collaborator, which summons so much about the political winds of the twenties and thirties blowing through the Parisian literary world, and about the postwar epuration in France, which Céline eluded by fleeing to Denmark, and which Robert Brasillach didn’t. Elude, I mean. (Whether this “fine literary writer” should have been executed for treason or not is, for me, a question one could settle one way at breakfast and the other way at dinner. Sartre or Camus, take your pick.) Anyway: Leiris, who writes the most pellucid and persuasive sentences. Whose abjection I welcome more than anybody’s egotism. His writings a bonanza of formidable insights conveyed with the unrushed elegance of a Saint-Simon. Leiris is incomparable, a Vermeer in a world of Han van Meegerens. Frail Riffs is pure pleasure, in the way Proust is pure pleasure—you can open to any page and just surrender yourself to the music of time that saturates it. The early entry in Frail Riffs, describing the prologues of Goethe’s Faust and their effect upon him as a teenager, is enough to turn any reader into a Leiris devotee.

—Gary Indiana

Emily Witt’s Health and Safety begins in Gowanus in 2016, where the Future Sex author is set to give a lecture called “How I Think About Drugs.” She speaks from a Google slide about Wellbutrin, which she used to take, and the distinction between “sort-of drugs” (pharmaceutical) and “drugs” (illegal). After quitting Wellbutrin, at thirty-one, Witt broke a yearslong illicit-substance fast by smoking DMT at Christmastime. This was the beginning of a drug journey of sorts, one involving ayahuasca retreats in the Catskills with her then boyfriend, a sensory-deprivation-tank attendant, and a large dose of mushrooms taken in a Brooklyn apartment. After her speech she meets Andrew, a Bushwick DJ. He soon introduces her to another context for and type of drug-doing: raving. She falls in love. They soon move in together at Myrtle-Broadway.

“Being in love made me happy,” begins chapter five, “and I lost interest in channeling all of my knowledge about nutrition, disease, and medicine into a life of perpetual risk management.” Witt began to see her former orientation toward health and wellness as narrow and individualistic, whereas raverly values were collectivist, abolitionist, and harm reductionist. To be one of techno’s real appreciators meant thinking through its lineage in Black American Detroit and how it morphed in Berlin clubs; it meant learning about Afrofuturism, Deleuzian metaphysics, and Narcan administration. It could all feel overly theoretical, because the real point of doing ketamine at Nowadays is having fun, but even the most pretentious scene fixtures were interesting in their own ways. Witt is intrigued by techno’s embrace of pessimism as praxis: a deep-house artist named DJ Sprinkles uses part of their set to drive home why they use the term transgendered instead of transgender, then tells their audience they’re all a bunch of normie losers. Sprinkles is compelling because their unapologetic manner gets at realer issues than does the tone-deaf #Resistance-era small talk that was unavoidable at the time in New York.

Witt’s partying coincides with Trump’s election, the beginning of the #MeToo movement, Parkland, Kenosha, the protests in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, January 6. The Trump administration disturbed many Americans’ sense that we shared a definite political reality; our widened Overton window, at least, began to reveal the racial and socioeconomic injustices that white, middle-class liberals had claimed ignorance of. During this period, Witt joined The New Yorker as a staff writer while attending Black Lives Matter protests on the side with Andrew. Health and Safety poses sharp questions about what it means to watch history unfold versus to participate in its making, and about what it means to write about brutality when your friends are in harm’s way. These questions don’t resolve, as if to remind that discourse has little impact on the machinations of capital and state violence.

Witt’s reflections on the loop of reporting assignments—like being sent to watch Lizzo play a Shake Shack–sponsored set at a D.C. March for Our Lives rally—and sleepless nights at Bossa Nova Civic Club that comprised her pre-pandemic life are spectacular. So are her extremely specific notes on tripping: “I just saw some patterns that faintly buzzed in the marker colors of my childhood—the ‘bold’ jewel-toned spectrum that Crayola started selling in the early 1990s.” While reading Health and Safety, I couldn’t stop thinking about how the defamiliarizing effects of psychedelics are not unlike those of a well-constructed sentence, the kind that catches you off guard with its accuracy.

—Signe Swanson

The Kármán line, in astronomy, is the definition of the edge of space: the line at which Earth’s atmosphere ends and outer space begins. It’s a geopolitical rather than physical definition—it’s about fifty miles above sea level, though it is not sharp or well defined, and below the line, space belongs to the country below it, while above it, space is free. Daisy Atterbury’s new collection of poetry, The Kármán Line, to be published by Rescue Press next month, describes the line’s psychological import, characterizing it as a clearly defined yet impossible-to-name boundary between the known and the unknown. From the poem “Sound Bodily Condition”: “I want to learn how to get at the thing I don’t yet know, the blank space in memory, the experiences I should have language for and don’t.” Atterbury’s book is at once a math-inflected lyric essay; a rollicking road trip; a field guide to Spaceport America, the world’s first site for commercial space travel, located near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico; and a collection of intimate poems.

Atterbury spells out how you can, in a few steps, arrive at a relatively simple equation for calculating the latitude of the Kármán line for any planet, (2𝑚𝜌(𝑟)𝐴𝐶𝐿𝑟=1), but though the math might be legible in the abstract, things get more complicated in concrete terms: “To work out the Kármán line on an extraterrestrial planet I suspect you’d need to know the temperature.” The book’s energy comes from its application of the idea of the Kármán line to borders of all kinds. “We are thinking a lot about mindset,” says a man on the radio in the poem “Uranium Yellow”: the distinction between thought and the mind is a kind of Kármán line between reality and metareality. “I think he calls himself a neurobiologist,” recalls the speaker: the blood/brain barrier is the Kármán line of the body. The Kármán line might even be the signature line that the speaker deletes “when writing / personal emails,” tracing the edge between the public and private virtual versions of the self.

In the poem “What the Boundary,” I hear in the title an echo of William Blake’s “The Tyger” (“What the hammer? what the chain? / In what furnace was thy brain?”). The Kármán line divides space into a Blakean fearful symmetry that makes the known world seem safer—we can measure it, mark its delineations, perhaps even explore all of it—but also makes the unknown that much more vast and wild. As much as we crave the escape beyond the Kármán line into the infinite, Atterbury writes, we fear in exact parallel what lies beyond what we can measure. The formula for the Kármán line is simple—having the variables to plug into the equation to get an answer is the impossible part.

—Adrienne Raphel

JONONE DESIGNS RUM BOTTLE

Jenny’s Art, Design and Architecture blog: Calling all performers!!! Scratch Platform – Sunday, August 31st 2014 – Four Bars, Cardiff

Sunday August 31st is the first of what will be a regular event happening every

other month. The idea is to give Live Artists, Sound Artists, Cabaret

Performers, Poets and other artists who perform an opportunity to show their

work (whether it is ‘finished’, ‘polished’, in development or otherwise) to an

interested and supportive audience. The showing will start at 7pm and the venue

will be open until pub closing time!

Any work that is designed to be performed to an audience needs at some point to

be performed!

It will be free to take part in and free to watch. There are no ‘rules’ as such

other than that any piece shouldn’t last longer than ten minutes – in order to

give everyone a fair chance. There will be no competitive element and we want

to encourage a very open, pressure free and supportive environment.

It’s a lovely intimate venue and we are able to provide some technical

assistance- we have a PA, lighting rig and access to a projector and screen.

Will will also be filming the event to offer the performers a copy of the documentation

(this will be free, basically bring a memory stick or external drive and we

will copy the footage to it).

At the end of each event we will have a performance from an invited artist. On

August 31st this will be Foxy and Husk

We hope to draw artists and an audience from the artist communities in Cardiff

and further afield. There will be an opportunity for the performers to display

business cards, CV’s and other information that they might wish to share. We

will also offer feedback forms that members of the audience can fill in.

If you would like to show your work then please can you send me your technical

requirements (will you need music playback for example or a microphone(s)?) and

give me a very brief breakdown of what your 10 minute piece will be.

bring your friends!

Wenatchee artist discusses landscape paintings – wenatcheeworld.com

Wenatchee artist discusses landscape paintings wenatcheeworld.com

Source link

Gérard Depardieu sexual assault trial postponed after actor’s no-show | Gérard Depardieu

The trial of Gérard Depardieu on sexual assault charges was postponed until next year after the actor failed to appear in court on Monday, saying he was unwell.

His lawyer Jérémie Assous had said the 75-year-old was “extremely affected” by ill health and that he had asked for the proceedings to be delayed until he could attend in person.

The health of the actor, who has had a quadruple heart bypass and suffers with diabetes, had declined because of the stress caused by the hearing, the court heard before it adjourned to consider the request to delay.

Depardieu was also said to be incapable of remaining seated for six hours. Medical certificates from a cardiologist and an endocrinologist were produced, declaring that the actor was not in a fit state to appear.

Informed that one of the alleged victims had travelled 400km to be at the hearing, Assous said he had requested the trial be postponed in a letter to the court last Thursday.

Lawyers for the two female plaintiffs deplored that they were presented with a “fait accompli”, and asked for the actor be examined by a court-appointed doctor and psychiatrist. Their request was refused.

Depardieu is being tried on charges of sexually assaulting two women while shooting the 2021 film Les Volets Verts (The Green Shutters).

Depardieu, an icon of French cinema who has appeared in more than 200 films, has denied accusations that he aggressively groped and made explicit sexual remarks to the women – a set designer and an assistant director. In an open letter published last year, he said: “Never, but never, have I abused a woman.”

The actor is the highest-profile figure to face accusations in French cinema’s version of the #MeToo movement, triggered in 2017 by allegations against the US producer Harvey Weinstein.

The names of the two women at the centre of Monday’s trial have not been made public. The set designer reported in February that she was subjected to sexual assault, sexual harassment and sexist insults while filming Les Volets Verts, directed by Jean Becker, in a private house in Paris.

The plaintiff told the French investigative website Mediapart that during the shoot Depardieu started loudly calling for a cooling fan because he “couldn’t even get it up” in the heat.

She claimed the actor went on to boast that he could “give women an orgasm without touching them”. The plaintiff alleged that an hour later she was “brutally grabbed” by Depardieu as she was walking off the set. The actor pinned her by “closing his legs” around her before groping her waist and her stomach and continuing up to her breasts, she said.

Depardieu made “obscene remarks” during the incident, she said, including: “Come and touch my big parasol. I’ll stick it in your pussy.” She described the actor’s bodyguards dragging him away as he shouted: “We’ll see each other again, my dear.”

On Monday the plaintiff’s lawyer, Carine Durrieu-Diebolt, told Agence France-Presse: “I expect the justice system to be the same for everybody and for Monsieur Depardieu not to receive special treatment just because he’s an artist.”

Durrieu-Diebolt added: “My client expects that the justice system will find Gérard Depardieu to be a serial sexual assaulter.”

The second plaintiff in the case, an assistant director on the same film, also alleges sexual violence.

Assous previously said Depardieu’s defence would offer “witnesses and evidence that will show he has simply been targeted by false accusations”. He accused the plaintiff of attempting to “make money” by claiming €30,000 (£25,000) in compensation.

The defence also asked for a further eight witnesses to be heard, which would result in the trial taking longer than originally planned. It is now scheduled to be heard on 24-25 March next year.

Anouk Grinberg, an actor who appeared in Les Volets Verts, told AFP that Depardieu used “salacious words … from morning till night” while on set.

About 20 women have accused Depardieu of various sexual offences, which he denies. The actor Charlotte Arnould was the first to file a criminal complaint. A judge has yet to rule on a request from prosecutors in August for Depardieu to stand trial for allegedly raping and sexually assaulting her.

Arnould and Grinberg were outside the courtroom on Monday, alongside a crowd of people supporting the plaintiffs.

In December last year the French president, Emmanuel Macron, shocked feminists by complaining of a “manhunt” targeting Depardieu, whom he called a “towering actor” who “makes France proud”.

Macron’s remarks followed the broadcast by an investigative TV show of a recording of Depardieu making repeated misogynistic and insulting remarks about women.

A Bungalow Renovation With Zen Aesthetic in Echo Park

Nestled on a scenic hilltop in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, Sue Chan’s residence is a blend of function and serenity, offering a zen escape while maintaining a dynamic space for entertaining. Designed by OWIU Design, the Echo Park Hillhouse home is a testament to thoughtful design that draws upon the beauty of its natural surroundings while maximizing functionality and comfort.

The home’s layout emphasizes a fluid connection between indoor and outdoor spaces, reflecting its elevated vantage point with sweeping views of East Los Angeles. OWIU integrated the natural landscape into the architecture, with large windows and an expansive deck seamlessly extending the living space outdoors. The open-plan design encourages easy movement between the newly renovated kitchen and living room, making it ideal for both quiet relaxation and hosting guests.

Throughout the home, lighting choices by iconic designers like Noguchi and Mario Bellini add character and elegance, while vintage furniture pieces, such as a Hans Wegner dining table and Eames chairs, infuse the rooms with timeless style. In the living room, handcrafted pieces like a custom carpentry bench and American White Oak bookshelves reinforce the home’s unique, artisanal quality.

A notable feature of the home is the raised platform in the bedroom, a subtle yet effective way of delineating the private space without the need for walls. This design element, which has become a signature of OWIU’s projects, promotes a sense of retreat and calm, perfect for Chan’s busy bicoastal lifestyle. The bedroom is also complemented by custom-made Japanese shoji doors that provide both aesthetic appeal and practical privacy.

The kitchen, co-designed with Reform, showcases an earthy warmth through its cedar and oak finishes, similar to that of a cabin while incorporating contemporary elements. Thoughtfully placed skylights flood the space with natural light, enhancing the home’s organic feel. Despite its modest size, the kitchen offers ample storage thanks to hidden compartments and floating shelves, demonstrating OWIU’s commitment to maximizing space without sacrificing design.

The exterior continues the theme of blending functionality with nature. OWIU carefully designed the fencing to accommodate existing trees, creating a fluid relationship between the built environment and the landscape. Outdoor spaces, including a custom patio and furniture from the HAY Balcony Collection, offer additional areas to enjoy the tranquil surroundings.

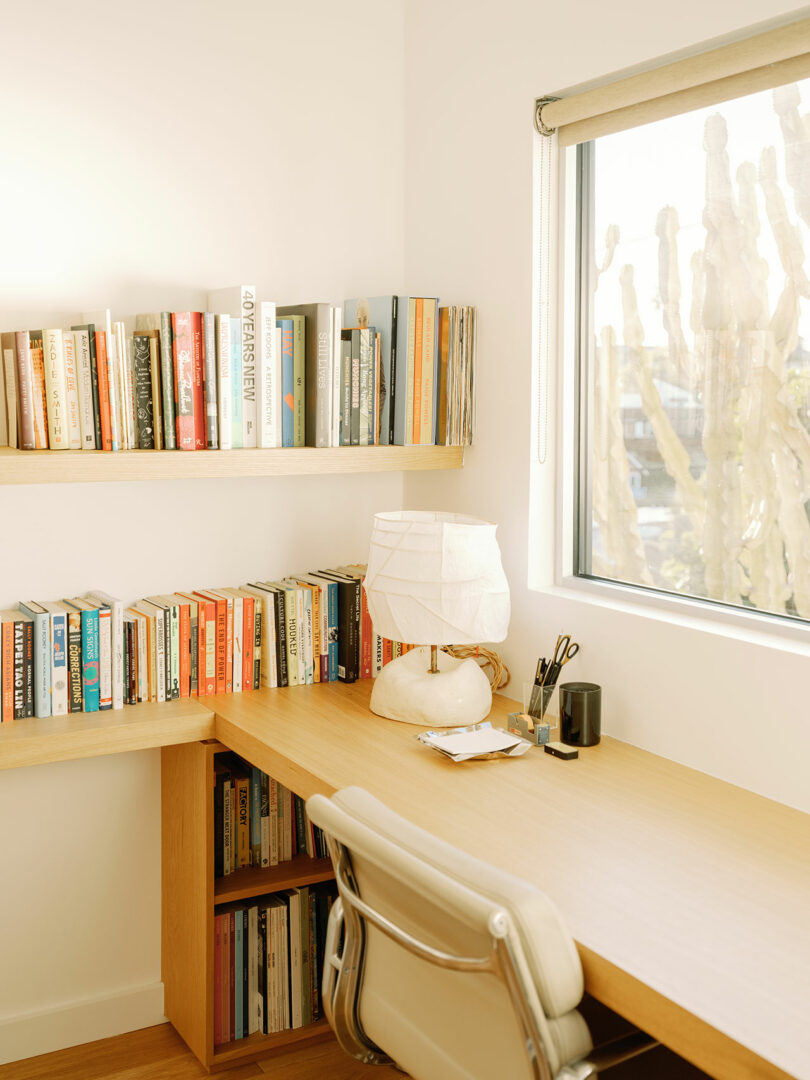

In addition to the main residence, OWIU designed a separate office unit on the property. Clad in cedar and oak, similar to the main house, the detached structure offers a quieter, more secluded atmosphere, ideal for focused work or retreat. The office features a large picture window framing the surrounding trees, keeping the occupant connected to the outdoors.

For more information on OWIU Design, visit owiu-design.com.

Photography by Justin Chung.

On democracy, Sir Lewis Namier and the struggles of the super-rich

Our Britain columnist has not lost all faith in his country’s parliament

Source link

“New Open Movie Captioning Requirement for DC Movie Theaters Begins” – PoPville

“New Open Movie Captioning Requirement for DC Movie Theaters Begins” PoPville

Source link

‘I wanted a hit!’ Bryan Ferry on recording Slave to Love in Bette Midler’s house | Pop and rock

Bryan Ferry, singer, songwriter

I’m not a musical detective, but I’d put my money on the inspiration for Slave to Love coming from Prisoner of Love by the Ink Spots, which I heard when I was five. My Auntie Enid’s husband was stationed in Europe with the armed forces and I think he picked up American records and brought the Ink Spots home. I still have the 78 RPM single.

I wrote the lyrics in a hotel room in New York, while pacing the floor at night. I’d done more esoteric things in the past, but I wanted something simple and memorable, a song for everyone. A hit! The first line – “Tell her I’ll be waiting / In the usual place / With the tired and weary / And there’s no escape” – set the scene.

I’d loved being in Roxy Music but, going solo, the world was my oyster. We had assembled a team of big guns, people like David Gilmour (guitar), David Sanborn (saxophone) and Nile Rodgers (guitar). Neil Jason had a swing to his bass-playing that suited the track down to the ground. Neil Hubbard had the most wonderfully soulful tone and we recorded him early on to build the song around him. The guitar solo in the middle is actually three interweaving guitarists: Gilmour, Keith Scott and Hubbard.

I did the video in Paris with Jean-Baptiste Mondino. It was beautifully filmed, with a certain chicness – all these beautiful girls and me in the background, which was how I liked to be. At the end of the video, I’m hugging a child, like a long-lost daughter or something. Good twist. It turned out this child actor was the daughter of someone I’d had dinner with, along with Salvador Dalí, in 1973.

When I performed the song for the first time, at Live Aid, the drummer broke his snare-drum skin, the bass was in a different tuning, Gilmour’s guitar wasn’t working properly, and someone had to tape another mic to mine because it wasn’t audible. But despite all that, the song took off pretty quickly and has been in lots of films. It’s fabulous when people identify with your feelings about something.

Rhett Davies, producer

I first met Bryan when I engineered a track on his 1974 solo album Another Time, Another Place. Then in 1979, when Roxy had got back together, I was pulled in to do a week’s work on the Manifesto album and stayed for 40 years. We had found a way to cut Dance Away, which they’d tried before but hadn’t pulled off. I suggested laying down a keyboard and rhythm box and building it up from there. As Roxy’s sound evolved from Manifesto to Flesh and Blood to Avalon, we kept that way of working.

Bryan’s Boys and Girls album felt like a continuation, just without Roxy. We started working on it at his house in Sussex with simply his voice and his CP-80 electric piano. We went to a studio in London called the White House, then went to Bette Midler’s house in New York. She’d had trouble sleeping and had built a soundproof room, so we set a studio up in there.

It was one of the most difficult tracks to finish and it went through a lot of lives. In the chorus, there’s a little keyboard phrase that came from another track we never got to finish, so we moved it into Slave to Love. Bryan loves having something straightforwardly passionate throughout a song, and on this one it was a cowbell. The drummer, Omar Hakim, recorded the big snare drum sounds in New York’s Power Station studios’ stairwell, which had a famous reverb.

Bryan was still working on the lyrics so the vocals came last, and it was the last track we finished for the album. Bob Clearmountain [mixing engineer] mixed it so many times in so many studios. He remembers falling asleep in Air Studios mixing it even more. It was finally finished at three in the afternoon. When we heard the completed song, there was just elation. When I listen to it now, I wouldn’t change a thing.

How Cheerleading Took Over Girls’ Sports

It is a huge part of the country’s arts scene, quietly flourishing and influencing new generations of dancers and choreographers. – The New York Times